Textual Object

Nicholas Sammond / University of Toronto

Columnist’s Note: Over the next three essays, I will trace the development of a pedagogical idea about exploring textuality, its realization in a syllabus, and its execution as a course. Each essay will approach the topic through one of three successive lenses: Bakhtin’s notion of heteroglossia, Lefebvre’s systematic analysis of social space, and finally new materialism’s troubling of the category of the reading subject.

Every age re-accentuated in its own way the works of its most immediate past. The historical life of classic works is in fact the uninterrupted process of their social and ideological re-accentuation. Thanks to the intentional potential embedded in them, such works have proved capable of uncovering in each new era and against ever new dialogizing backgrounds ever newer aspects of meaning…. [1 ]

This is a story about interpretation.

This academic year, in the rotation for graduate instruction I was slated to teach a class that I had eyed with interest for a long time: “The Textual Object.” It had first been designed as an elective for our MA program, but had eventually migrated into the graduate core. The colleague who first conceived of and designed the course had built it around a simple but elegant conceit: take a single film and spend an entire semester exploring as many aspects of it as time allowed. Her choice was Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958), and the class approached it through the lenses of adaptation, criticism, auteur theory, genre studies, revision, stardom, apparatus theory, semiotics, remediation, and postcolonial theory. The students were divided into small groups, each of which was responsible for creating part of a website, The Touch of Evil Project, which would eventually collate their research.

Coming from a disciplinary formation not in cinema studies but in media studies, I was less interested in any single film text or in many of the questions/problems posed by postwar film theory. But I was intrigued by playing with the notion of the text, how the ascription of an overarching textuality to a set of perhaps disparate objects might (or might not) encourage a collective of students to reproduce those objects as a single, coherent text. The challenge in altering “The Textual Object” was at least twofold: on the one hand, the course had become storied among passing generations of MA students, and any deviation from its original organization might alienate them; on the other hand, following too closely a script of someone else’s design might lead to a wooden course—functional, creaking along, but not animated by my own interests. After considering a number of possibilities, I settled on a “text:” the amusement park Disneyland, which opened in Anaheim, California, in 1955. Deeply imbricated in the cinematic, but arising in the much broader landscape of the intermedial history of American amusements, the park had a coherence of its own, yet was also comprised of a whole range of intertexts, and it allowed for, even encouraged, a plethora of metatexts—everything from chronicles of family vacations to guerrilla interventions into its fastidiously regulated landscape.

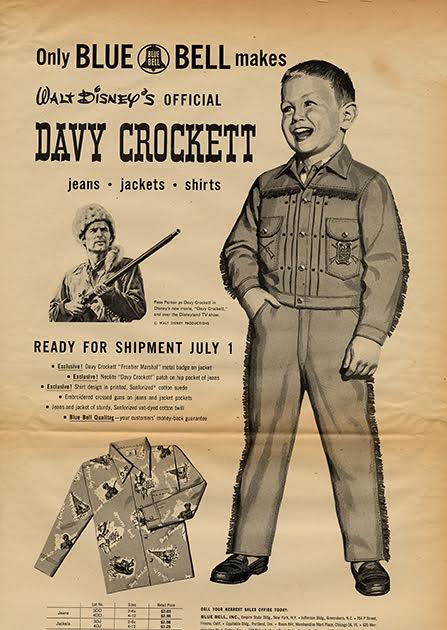

The challenge of choosing the text was less daunting, though, than balancing the disciplinary requirements of an MA program against the inherently interdisciplinary approach that a multivalent intertext such as Disneyland suggested. Our MA program expects its students to develop an advanced competence in film theory, film history, and textual analysis. The last of these, of course, is the exact ambit of “The Textual Object,” and its underlying assumption has been that MA students, as scholars in training, would do best working intensively with a significant narrative film from a well-established canon, one surrounded by substantial critical and scholarly discourse. Hence Touch of Evil. Disneyland, needless to say, is not a film. Disneyland (1954-1959) was an anthology television series, in many ways little more than an elaborate advertisement for the park and for other Disney commodities, and as an object has failed to attract sustained, critical scholarly engagement—at least not enough around which to build a course.

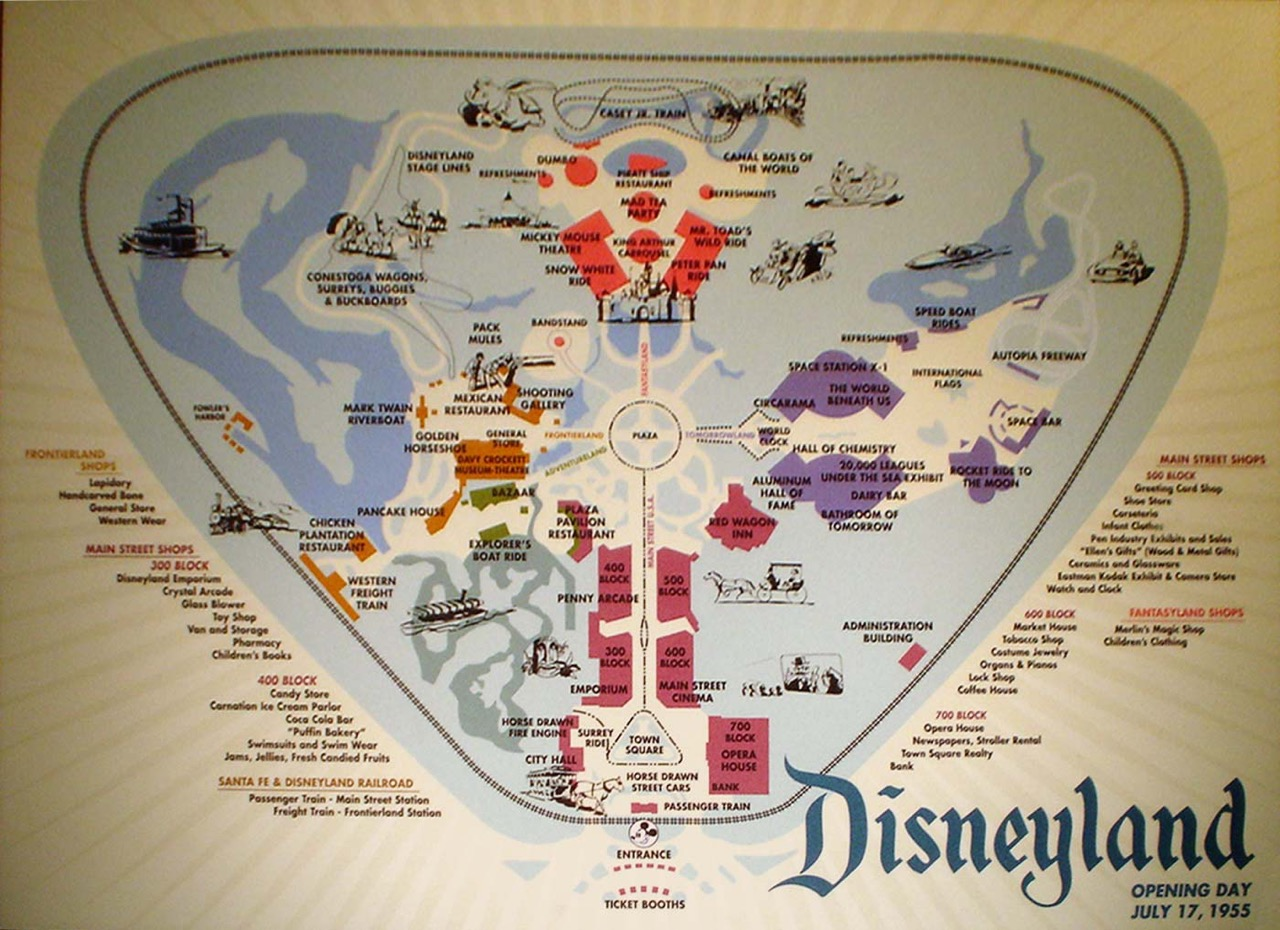

Disneyland the park, on the other hand, is not only a complex matrix of intertexts, it is also a narrative text unto itself. [See Figure 1] Although visitors can diverge from its fundamental organization principles, the park has a logic, an order, a temporal continuity that is hard to ignore. Immediately after entering, visitors find themselves in the Town Square of Main Street U.S.A., which is loosely modeled on Walt Disney’s second home town of Marceline, Missouri. Disney’s first home town was Chicago, a city less easily rendered in the Rockwellian, turn-of-the-century tones of Main Street U.S.A. After Marceline, the Disney family moved to Kansas City, where Walt would begin his animation business, but that city was also a little too urban to serve as the model for Main Street. In that Disney claimed that his/its park was meant to transmute the decidedly more urban and working-class model of the Coney Island complex of amusement parks (Steeplechase, Luna Park, and Dreamland), and more elaborate but perhaps too European parks such as Denmark’s Tivoli Gardens, into a more family-friendly (i.e., white, middle-class, and heteronormative) and middle-American register, Chicago (hog butcher to the world) and Kansas City (the “Paris of the Plains,” a.k.a. Cowtown) pointed in the wrong direction. Marceline, like the quaint town in the 1935 Mickey Mouse short The Band Concert, evoked small-town living on the cusp of the Industrial Revolution. Passing along Main Street U.S.A. the ideal visitor arrived at a central plaza from which, arranged like spokes on a wheel, were avenues to the different intertextual “lands” that comprised the greater Disneyland. Moving in a clockwise direction, forward in time from an ideal past toward an ideal future, these were Adventureland (the natural world), Frontierland (westward expansion); Fantasyland (fairy tales for the civilized bourgeoisie), and Tomorrowland (technological utopia). Having rounded the clock, one returned down Main Street U.S.A. (presumably a better American), exiting into parking lots that had replaced the orange groves of Anaheim, California. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the narrative of Disneyland the park reproduced the constituent parts of Walt Disney’s biography, the ur-American man: deeply in touch with nature, both human and animal (Adventureland); the quintessential white American, once described having “Irish, Canadian, German, and American blood in his veins” (Frontierland); imbued with a sensibility inherently good for children (Fantasyland); and a tinkerer with an eye toward a better future through technological innovation (Tomorrowland). Entering before the anthropocene, in the midst of nature primordial, one found one’s place in the proper order of things. Continuing onto the frontier one witnessed the uneasy encounter between European settler society and that unbridled nature, the taming of a landscape and its people (the two imagined as one) in the service of Manifest Destiny. Yet every colonist, even Dan’l Boone, never goes completely native, always carries the metropole within, so fairy tales must speak to and for the better angels in children, guiding them from nature into culture with a sure, gentle hand at their backs. And finally, as with all utopias, an ideal future erases any lingering failings and contradictions in the present, offering absolution tomorrow for today’s sins.

There is a tension here, of course: the park as text was designed as a series of intertexts, its mode of ideological address hailing (via Mickey’s waving hand) Disney’s ideal subject, circa 1955. Yet the park has continued to change, its design updated and refined since that time, with layers accreting around the welcome given to subsequent historical subjects. And, as if that weren’t enough, the original intertexts themselves have continued to change, in and of themselves and in relation to each other. And, as if that weren’t enough, ideally the students in this course, as they read the textual object that is Disneyland, will enter into conversation not only with the text itself, but also with its various interlocutors. “Along with the internal contradictions inside the object itself,” Bakhtin reminds us, “the prose writer witnesses as well the unfolding of social heteroglossia surrounding the object, the Tower-of-Babel mixing of languages that goes on around any object; the dialectics of the object are interwoven with the social dialogue surrounding it.” [2 ] Flowing through and conversing with the park are longstanding discourses and practices such as the wild-west show, museum of natural history, children’s literature, and utopian science fiction, each of which with its own canon and its own criticism.

So, following this conceit of the park-as-narrative, the redesigned course traces the narrative line described above and, following Bakhtin’s notion that every text is heteroglossic, assembles within each of its five intertexts a further set of intertexts—critical essays and media texts—guides (or what Disney calls “cast members”) meant to stand between the textual object that is Disneyland and the students it seeks to interpellate. Drawing on the history of American amusements, of nature documentaries, of the extreme violence repressed in celebrating the colonial enterprise, of the fairy tale’s “uses of enchantment,” as Bettelheim put it, and of the gentle brutality of technological utopianism, the course will ask the students to (re)assemble Disneyland-as-text as a dialogic creation, speaking to and through fantasies of the sovereign individual whose apotheosis was Walt Disney himself. [3 ] An auteur in a register different than Orson Welles, but an auteur nonetheless, Disney was and is, as some have been wont to say, the Guiding Spirit of the land that bears his name.

At the same time, however, the conceit that Disneyland is a text is just that: Disneyland is also a place, a set of spatial relations artfully organized to isolate thematic differences and contradictions, and to locate its visitors within particular secondary narratives at particular moments. So that the students in this course don’t become too comfortable with the metaphor of place-as-text—which might lead to seeing the text/place as having a unitary transparency—at key moments the course will shift registers and examine the spatial relations operating in the park. Rather than opting for critical geography such as that of Harvey or Giddens, however, the course (and the next essay in this series) will consider Henri Lefebvre’s approach to critical spatial analysis. Lefebvre developed his model in response to what he thought were overly fanciful applications of the concept of space by a range of mid-twentieth-century scholars, including Kristeva, Derrida, and Foucault. Whether his efforts were ultimately productive or useful, Lefebvre sought to create a systematic critical methodology for understanding the production, regulation, and disruption of space as a set of social phenomena. In that the conceit of “place-as-text” might well have begged Lefebvre’s scorn, it may prove a useful counterpoint for students who are disinclined to book an extended stay within the metaphor.

It is not for nothing that Disney calls Disneyland “the happiest place on earth.” Implicit in that claim is that all other spaces make (of) their occupants, their readers, less happy people—that existence in the space of the quotidian is not as happy as the life lived within a place carefully managed to limit or avoid contradiction. Disney’s devotees seem to share this sentiment. So, the title of the course, “The Textual Object,” suggests one last lens for understanding how Disneyland might serve as a text, as well as the limitations to that approach: a text as subject, as the deliverer of a narrative, makes of its reader an object, an other. Disneyland, fabled for its crowd management skills, performs an affective sleight of hand in which within the crowd, the aggregate that Disney manages, the individual feels addressed, happy. The course, then, may end by troubling the notion of a stable relationship between Disneyland-as-text and its readers. Rather than opting for a reader-response approach, such as that of Fish or Radway, or troubling the idea of authorship, as would Barthes or Foucault, the course may explore whether it is productive to erase the clear lines between the park’s lands and its visitors (the text and its readers) and see them all as actors in a network that produces… happiness.

This last approach will not replace a narrow critique of Disney’s politics, a la Dorfman or Zipes… as those have their value, nor will it supersede a textual reading of the park. Rather, it will pose a problem for the class by asking it/them to bring these contradictory approaches into conversation, to weigh textual, spatial, and affective approaches as means to critically engage with the park’s constituent and constitutive fantasy… a nostalgia for a past when the individual was indeed sovereign, when the landscape spoke clearly, when each and everyone could imagine a future in which all boats rose on the swelling tide and were carried gently along on the calm, sure current of History, a current that moved “straight on to tomorrow” and then to Tomorrowland.

To be continued in Flow 22.04: the spatial turn, and the media and readings through which the class will visit each land.

Image Credits:

1. Theme Park Investigator.

2. Author’s Collection.

3. Author’s Collection.

Please feel free to comment.

- M. M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination. Michael Holmquist, ed. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holmquist. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 421. [↩]

- Bakhtin, M. M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Michael Holquist, ed. Trans. by Caryl Emerson and

Michael Holquist. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1981. 278. [↩] - Bettleheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. New York: Vintage Books, 1976. [↩]

Pingback: Textual Object Nicholas Sammond / University of Toronto – Flow