Losing Cosby

Bambi Haggins / Arizona State University

This began as an article on the fall of a Black comedy icon. After watching the Dateline interview with 27 of the 55 women who have accused Bill Cosby of being a sexual predator, on the same day that the 78-year-old comedian was forced to answer questions about an alleged 2008 attack at the Playboy Mansion, I had to question why I feel so personally angered and injured by this history of despicable actions.

As a Black Post-Boomer, Pre-Xer, eight-track tapes of Bill Cosby’s comedy provided my nap soundtracks. I grew up on The Electric Company and Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids, and, later, on The Cosby Show. As a working class kid, I was weaned on the uplift-tinged stories of “you can’t be as good, you have to be better to get half as far.” In other words, although my folks were not in the same socio-economic zip code as the Huxtables, they were in the same ideological region.

As a middle-aged media scholar, I see 20th-century televisual iterations of Cosby as the poster boys of (Black) American exemplarism—whether as the integrationist Super Negro spy, Alexander Scott in I-Spy, or the patriarch of the Super African American Huxtable clan in The Cosby Show. The new millennial Cosby has positioned himself as the self-appointed cultural and moral arbiter for Black America and, most recently, has been called a serial predator.

In truth, losing Cosby—the desire for and belief in the illusive and impossible zeitgeist of his comic and socio-political discourse—started happening a long time ago. In Cosby’s infamous “Pound Cake” speech at the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education in 2004, his words seemed rooted in a deep personal disappointment about how younger generations and the Black underclass had let him down. Indeed, Cosby’s turn towards activism and his “call-out” dates across the country in the late 2000s centered on the need to produce a brand of Blackness informed by self determination-fueled, socially and politically conservative tenets, which required that the less than talented 90% pay heed when he calls them out for behaviors that keep them “aspirationally challenged.” As Ta-Nehisi Coates stated in his 2008 article in The Atlantic,

As Cosby sees it, the antidote to racism is not rallies, protests, or pleas, but strong families and communities. Instead of focusing on some abstract notion of equality, he argues, blacks need to cleanse their culture, embrace personal responsibility, and reclaim the traditions that fortified them in the past. [1]

While Cosby was not alone in this ideological directive, decades of his not “acting right” and not being the exemplar that he purported himself to be, undermined what Michael Eric Dyson referred to as his “Afristocrat in Winter” [2] pronouncements as well as his legacy. It is both fitting—and profoundly disturbing—that the catalyst for his downfall came from another Black comic. When the video of Hannibal Buress’ 2014 Philadelphia show went viral, everything changed.

[Cosby] gets on TV, ‘Pull your pants up, black people … I can talk down to you because I was on TV in the 80s.’ Yeah, but you rape women, Bill Cosby, so turn the crazy down a couple notches … When you leave here, Google ‘Bill Cosby rape.’ That shit has more results than ‘Hannibal Buress.’

Needless to say, Buress’ rant did not cause over thirty-five women to tell their stories about Cosby’s predatory ways in New York Magazine [3] nor did it necessarily raise questions about why, when some of these women came forward a decade before, it was their motivations and not Cosby’s actions that were called into question. As the title of Barbara Bowman’s Washington Post article stated bluntly, “Bill Cosby raped me. Why did it take 30 years for people to believe my story? Only when a male comedian called Cosby a rapist did the accusation take hold.” [4] Well… denial is a powerful thing—particularly when it threatens mythologies with which we have become comfortable. Who wanted to believe that “America’s Dad,” a Black comedy icon, was a sexual predator?

Yet, cracks in the idealized veneer of Cosby could be seen in years past. On a 1969 comedy album, Cosby has a long bit regaling the merits of the mythological aphrodisiac, Spanish Fly. While one might excuse this as a sign of more regressive times, Cosby reiterated this bit with some nostalgia on his 1991 appearance on Larry King Live: “Spanish Fly was the thing that all boys from age 11 on up to death…will still be searching for Spanish Fly.” The romanticizing exchange went on with Cosby stating, “…you put it in a drink,” and King replying, “That’s right. Drop it in her Coca-Cola – It don’t matter.” Then a chuckling Cosby responds “It doesn’t make any difference. And the girl would drink it,” and an equally delighted King finishes with “And she’s yours.” [5] In hindsight, the casualness and flippancy of Cosby’s words seems downright chilling. The image of the women on Dateline comes to mind: hands raised when asked if Cosby had drugged them. Cosby’s directives, offered from upon high, and his “public moralist” position empowered Judge Eduardo Robreno to release the 2004 deposition transcripts detailing how the comic utilized Quaaludes.

The rapidity of Cosby’s downward spiral has shaken folks throughout the Black community, although, the impact may have some generational buffering. Black millennials, who saw The Cosby Show on Nick at Nite, have no real experience with him other than as a sitcom star or a pitchman. They may know about his accolades but they came of age with Black America’s scolding senior not the universalist funny man. When my student, Raymond Reid, a Black male born after The Cosby Show’s heyday, ranted unendingly about how much he hated Cosby’s pomposity, it made me wonder whether Cosby’s object lessons for Black success rang as hollow for Buress as they did for my student.

Cosby has lost his perch on the hierarchy of respectability and, along with the revoked honorary doctorates and severed ties with universities, the NBC series, and the Netflix special, he may be losing more—if the October 9 deposition reveals as much as the last did. Yet, what still remains both angering and painful for folks in the Black community is that Cosby was “our” icon and now he has become “our” shame. Brittney Cooper gave voice to what I feel:

The thing that I am most angry about besides Cosby’s violent, predatory acts toward his female victims is the collective sense of shame and disappointment that rests on the sagging shoulders of black folks in this moment. … Cosby now legitimates every awful thing that white people have been conditioned to think is true about Black men. If the innocuous, lovable, jello-pudding-pop man can’t be trusted, then no Black man can. [6]

In the end, this is about more than the fall of an icon—at least for us it is.

Image Credits:

1. Bill Cosby, the Fallen Comedy Icon (author’s screen grab)

2. Cosby’s Previous Jokes Carry New Meanings (author’s screen grab)

3. Cosby’s Accusers Speak up on Dateline (author’s screen grab)

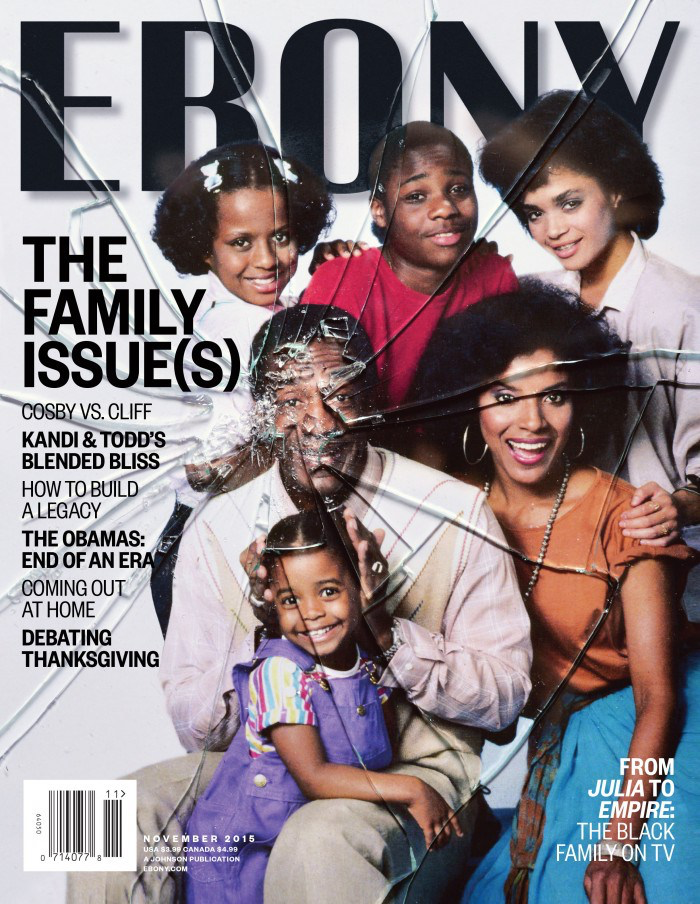

4. A Shattered Image

Please feel free to comment.

- Ta-Nahesi Coates, ‘This Is How We Lost to the White Man’ The audacity of Bill Cosby’s black conservatism. The Atlantic, May 2008 http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/05/-this-is-how-we-lost-to-the-white-man/306774/ accessed 9/1/15 [↩]

- This is the title of the first chapter in Michael Eric Dyson’s 2006 book, Is Bill Cosby Right?: Or Has the Black Middle Class Lost Its Mind?. Afristocracy speaks to what Dyson, and other cultural critics see as the classism and elitism in the Black Middle and Upper Middle Class. [↩]

- Ella Ceron and Lainna Fader, “35 Women and the empty chair.” New York Magazine, July 28, 2015 http://nymag.com/thecut/2015/07/35-women-and-theemptychair.html. Accessed July 30, 2015. [↩]

- Barbara Bowman, Bill Cosby raped me. Why did it take 30 years for people to believe my story? Only when a male comedian called Cosby a rapist did the accusation take hold.” The Washington Post Nov. 13, 2015 https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2014/11/13/bill-cosby-raped-me-why-did-it-take-30-years-for-people-to-believe-my-story/ accessed 2/13/15 [↩]

- “Creepy Bill Cosby interview resurfaces, describes dropping ‘Spanish Fly’ in women’s drinks” The Griot, http://thegrio.com/2015/01/13/cosby-interview-spanish-fly/ accessed 3/15/15 [↩]

- Brittney Cooper, “Black America’s Bill Cosby Nightmare,” Salon July 9, 2015, http://www.salon.com/2015/07/09/black_americas_bill_cosby_nightmare_why_its_so_painful_to_abandon_the_lies_that_he_told/ accessed 8/10/15 [↩]

The recent verdict regarding Cosby has had me thinking about this issue more than usual these past few days, and I found this piece to be extremely insightful and covers issues that need to be talked about, but I rarely hear covered in media. While this verdict finally represents some small amount of justice for Cosby’s victims, in the discussion of this outcome, some of the discourse represented in the piece above gets lost. Every piece of media I run across refers to Cosby, as you mention, as America’s Dad, and while it’s true that that was the reputation and persona he built, it was remarkable because he accomplished that feat as a Black man at a time when few Black role models were to be found so visibly on television. He represented an upper middle class loving father and created an image that even white America at that time was comfortable inviting into their homes, not an easy task in a landscape of television sitcoms practically defined by the white family. The Cosby Show did much to normalize the idea that a Black family could enjoy the kind of success and harmony of the white sitcom family. Though not the first Black led sitcom, the praise for its decreased stereotyping and wide appeal were well earned. By virtue of this show and his other work, Cosby cultivated a celebrity both on and off screen as an icon and role model in the Black community and by doing that came to be America’s Dad, and his identity as a Black man in inextricable from that achievement and which made that achievement all the more historically impactful. His work made America’s Dad a Black man.

As you so rightly point out, the betrayal felt in the wake learning of his actions is not merely amplified by his fatherly persona, but what that persona means in the context of the Black community. His work did much do improve Black representation in the media, and yet it was based on a lie and pomposity over his own success at hiding that lie to become an icon. Though his actions cannot go back and rewrite the history of that representation completely, he has certainly betrayed those who saw him as a role model for the Black community.

I grew up with Bill Cosby. I’m a 63 year old white woman. In the Army I was raped and sodomized after being drugged by Superior. I was cosbeed. I hate the man I wish him hell for eternity and how dare he take those lies and profess himself to be something almost omnipotent. Fuck him and anybody that agrees with him or follows him I wish he could be forced to watch Stone castration and then forced to eat his own testicles