Using Digital Tools for Collaborative Discovery: Assurances and Ambivalences

Leah Shafer / Hobart and William Smith Colleges

As a media studies professor at a small liberal arts college, I struggle to engender genuine, invested, critical conversations amongst my students. Because of the baroque structures of the students’ social lives outside the classroom – structures whose outlines are clear to me but whose details escape me entirely – my students find it difficult to separate what they see as their personal, social identity from their scholarly, intellectual identity. This means that they are extremely reluctant to critique each other’s ideas and to reveal (or even develop) their own investments in ideas, causes, or theories. One solution I have found to this problem is to design learning activities that ask students to work in groups, to utilize digital tools that allow them to produce and assess data sets in order to construct consensus, and to build time for reflection and revision into the process of responding to the collaboratively produced analyses. The solution is not without its own problems: I’m both incredibly pleased with the results and deeply uneasy about the process. But, as I will discuss here, this push and pull has become generative and has provided productive obstructions that have provoked rich and dense scholarship in my media studies classrooms.

Because I am a feminist pedagogue with scholarly interest in activist media, avant-garde aesthetics, and digital humanities work, I am deeply invested in collaborative work as both a pedagogical praxis and as a scholarly enterprise. [1] Collaborative work productively decenters hegemonic discourse and invites multiple, diverse points-of-view into conversation. But students hate group work. [2] When you let them pick their own groups, the classroom transforms into a middle school lunchroom – or, worse, a gym – where cliques form immediately and someone ends up picked last.

When you randomly assign them to groups, extreme awkwardness prevails and more often than not you end up with alienated and angry students in office hours the week (or day) before a project is due. When you carefully craft groups you are faced with a dilemma: should you try to spread the underachievers/slackers out amongst the hard working/shining stars? Or, do you create a caste system by putting the best students together and setting the struggling students up for mutually assured destruction? It’s very difficult, even in an era of grade inflation, to get undergraduate students to focus on process and developing ideas rather than final grades – and group work can make grade negotiations extremely fraught. [3] But, as I say to my students every semester: no matter what you are going to do in your life, you’re going to have to work with other people. And, for the most part, other people are the worst. If, however, you have the skills to work with others systematically, intelligently, and effectively, you’ll be way ahead of the game.

One of my current attempts to address this problem has been the design of courses that include a series of collaborative lab assignments. In one of my current courses, there are two major lab-based projects, each of which is composed of a sequence of three group assignments, and each group assignment is made up of a different grouping of students. Students are assigned to these groups both randomly and systematically: the groups are not designed around aptitude, they’re just groups that change entirely for each assignment within the lab. This way, individual students remain the constant across the three graded assignments within the larger lab project. This helps to ameliorate their anxieties about being “stuck” in a bad group, for example. It provides me with a wealth of assessable data when generating grades. And, it allows students to work with a diverse set of responses and ideas while developing a coherent final product. It also gives them permission to cultivate relationships with each other that are not social. By “forcing” them to work with different people, I am freeing them from the social stigma of “choosing” to work with different people. It’s a depressing bit of social engineering, but it’s effective.

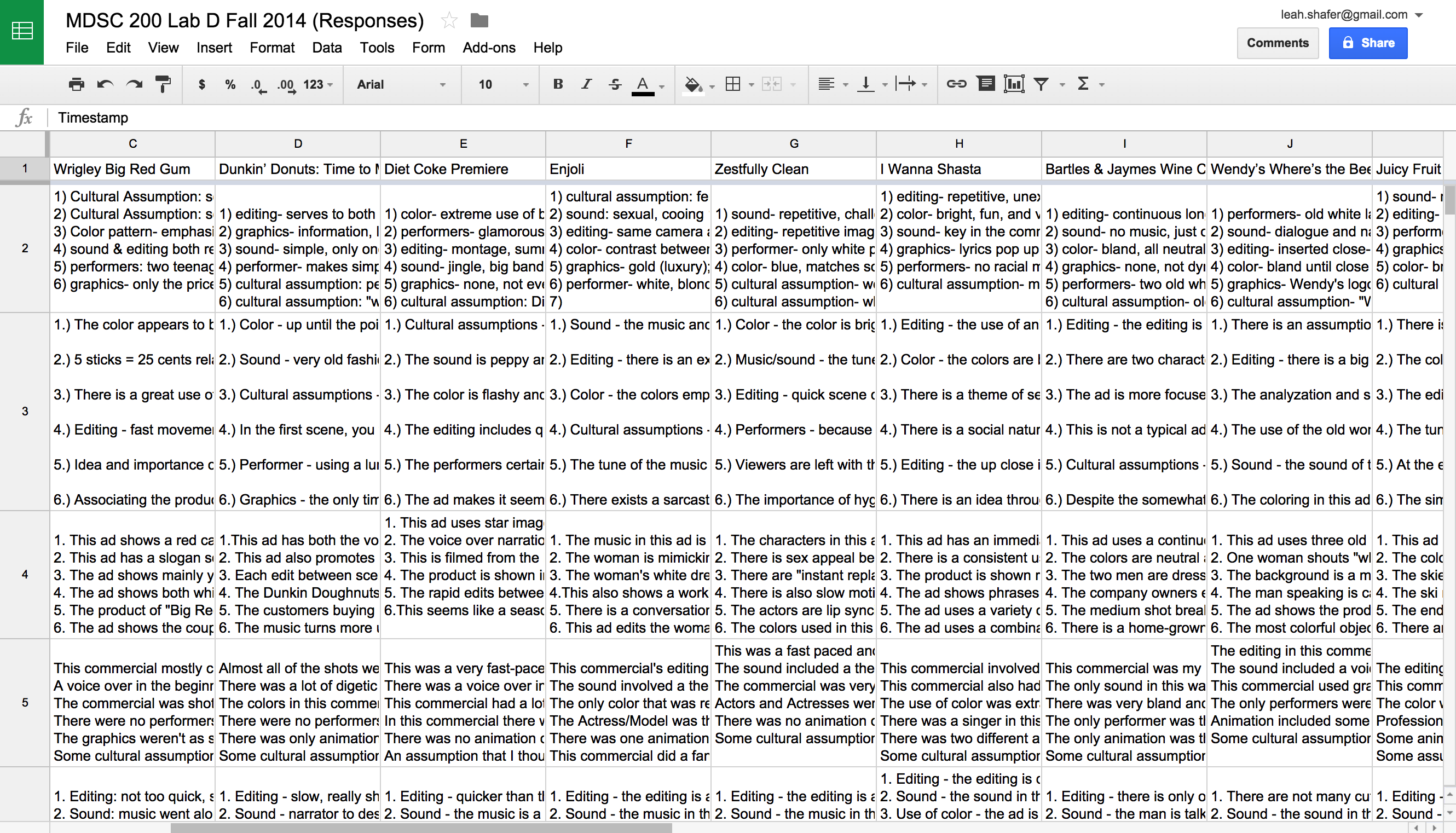

The second element of the solution lies in the way that the groups collaborate within each lab assignment. This element embraces the generative spirit of Digital Humanities 2.0, which models for our students the value of “the open, the infinite, the expansive, the university/museum/archive/library without walls.” [4] By designing lab assignments that collect student responses as data, students are invited to integrate their individual responses within both their small group and within the responses of the other groups as well. Each assignment within the lab asks the students to analyze a media object. (In the case of this current course, the objects are television commercials.) The students in each group work together to answer a set of standardized questions about the media text that have been formatted as a Google Form. After each group has submitted their responses to the questions, a second set of questions directs them to the spreadsheet of answers that has been generated by the Google Form. They read all of the groups’ answers to the standard questions. They are then tasked with analyzing the similarities and differences that they observe in the collection of answers to the standardized questions. We discuss, rank, and elaborate upon the answers in a classroom discussion. We then use the assessments of those collective answers to build, collaboratively, an analysis of the media text in question.

Resources like Google Forms are free, [5] sexy, user-friendly, and assessment ready, which is awesome, but also problematic. As this exercise is meant both to address a specific media text AND to model collaborative strategies for future work, the use of the Google Form can be distractingly sexy: the collaborative generation of ideas can fail to be the focus when the collection mechanism for those ideas is so slick. Further, it’s important for things to be user-friendly so students will embrace the process of analysis, but is complex analysis truly meant to be user-friendly? Isn’t struggle an important part of thinking? The ease of use can’t be allowed to convince students that the task of thinking is easy. And, I am deeply conflicted about assessment. On the one hand, especially given the precarity and unsustainable workload of most teaching jobs, any tool that streamlines assessment holds value. But on the other hand, trendy assessment tools capitalize on invisible labor and foreground metrics: two things that faculty should be deeply suspicious of in the era of the neoliberal. Further, shouldn’t students in the humanities be thinking outside the box, rather than in it (in spreadsheets)? And, even though it’s perfectly true that textbooks are, themselves, products of consumer culture, it’s unsettling to rely on branded utilities in order to teach a course that calls branding into question. Even though it’s a teachable moment, it’s still queasy-making.

In any case, the baroque architecture of this lab assignment tends to dismantle the baroque architecture of the students’ social sphere, at least long enough for them to open up to each other and to find ways of working together. The goal of the lab exercises is the creation of space and time for reading, researching, analyzing, writing, editing, and revising. This particular structure, which utilizes digital tools in order to scaffold collaborative acts of analysis, rewards individual initiative and retains individual points of view while capitalizing on the fruits of collectivity and collaborative labor. It creates critical conversations, which is the point of the whole enterprise.

Image Credits:

1. Collaboration is key.

2. Student being forced to do group work (author’s gif).

3. Spreadsheet of student responses (author’s screen grab).

4. Collaborative labor yields awesome results (author’s gif).

Please feel free to comment.

- Recently, a colleague who grew up behind the Iron Curtain posted on social media that her experiences as a youth have made her deeply suspicious of the zeal for “collaboration” in academe. (I feel similarly about the number of times in a day that a website asks me to click on “submit.”) I take her point, but I remain committed to collective work in the classroom and among scholars. [↩]

- Honestly, when I was in college I hated group work. My Tracy Flick-like tendencies led me to bossily do all the work, which overtaxed me, alienated me socially, and deprived me of the type of enriching and generative conversations with my peers that would have led to more interesting and nuanced work. [↩]

- My colleague Lisa Patti and I have experimented with different modes of self-reflection in order to ameliorate the question of who in the group did what work. For more details, see our essay: “Extreme Searching: Multi-Modal Media Research” in The Journal of Interactive Technology & Pedagogy http://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/extreme-searching-multi-modal-media-research-2/ [↩]

- “Digital Humanities 2.0: A Report on Knowledge” Todd Presner 2011 accessed February 2, 2013, http://cnx.org/content/m34246/1.6/. [↩]

- “Free” if you have access to a computer and electricity and an Internet connection, that is. [↩]