The Informal Economy of the Amateur Archive: Collectors as Cultural Intermediaries Shawn VanCour / New York University

It’s a Friday morning in October 2014, and I am interviewing Marty Biniasz of Buffalo, New York, on behalf of the Library of Congress’s Radio Preservation Task Force. Marty is a former news anchor, past president of the Buffalo Broadcasters Association, and holds a personal collection of several hundred audiocassettes with over 20,000 hours of airchecks featuring local DJs, news, and public affairs programming from more than a dozen Western New York stations. He and fellow collector Steve Cichon are authoring the first book on the history of Buffalo broadcasting, and together they have helped preserve thousands of films, audio, and pieces of broadcasting ephemera for their local historical group, Forgotten Buffalo. You have likely never heard of either of them.

In current media studies parlance, we might categorize the forms of collection and preservation pursued by these individuals as part of an “informal economy” of archival practice, existing beyond the boundaries of official broadcasting institutions, below the level of chartered libraries and museums, and off the radar of most academic media historians. These bottom-up modes of archivization form the invisible substrate on which much of the history of local broadcasting may be written, impacting what sounds can enter the historical record and what cultural significance is accorded to them: if journalists, as the saying goes, write the first draft of history, the amateur archivist is the first to gather and organize its traces. To facilitate effective dialogue between these often neglected custodians of local broadcasting history and official keepers of national cultural memory, we must recognize the operational logics of the amateur archive, whose informal economy I suggest may be broken down into three smaller, component economies:

1. Moral Economy (Bootlegging as Public Service)

In a recent post on OTR fandom, Nora Patterson notes the instrumental role that bootleggers played in preserving programs not actively archived by commercial networks. The concept of “moral economy” is useful for explaining such activity, adapted from E. P. Thompson’s formulation by scholars of fandom to describe responses to perceived breaches of contract between producers and their audiences. In a 1997 article for the New York Times, critic Allan Kozinn boldly declared “Bootlegging as a Public Service” that righted the wrongs of an entertainment industry whose overzealous antipiracy efforts had also threatened more ephemeral content unavailable through commercial channels:

“From a broader cultural perspective, bootleggers are doing something crucially important . . . . preserving recordings that would not otherwise have been kept, including material taped from radio.”

Fandom is by no means a precondition for bootlegging, nor is amateur archivization necessarily the province of fan studies. Nonetheless, the concept of a moral economy seems in many ways applicable: the bootlegger responds to failures by established institutions (both commercial and cultural) to adequately preserve and value local broadcasting, producing an unofficial, grassroots archive to complement the official one.

Moving this amateur archive into channels of official memory involves not just a physical transport of recorded material but also a negotiation between traditionally opposed structures of cultural valuation. Intended acts of cultural recognition may in this context be easily mistaken for symbolic violence – an attempted cooptation or perversion of alternative knowledges whose legitimation has been repeatedly denied in the past.

2. Fiscal Economy (Gray Markets)

Informal economies are never wholly separate from nor resistant to economies of capitalist exchange, occupying the space of so-called “gray markets.” As Clinton Heylin notes in his history of bootlegging, this “secret recording industry” has always been subject to market forces, with bootleggers cultivating markets neglected by official producers, who may in turn claim them for their own once their value has been proven.

While bootlegging is often not for profit, neither does it operate outside the sphere of monetary exchange. If recordings hold the stored labor of the musician, as Jacques Attali claims in his political economy of music, so too do they that of the bootlegger, who may seek appropriate compensation for his time and materials. Ed Brouder’s Man from Mars site, for instance, lets collectors view databases of his own holdings and purchase copies of desired recordings, for which the site explains, “Fees charged are for studio time, tape stock, office supplies, and postage only.” Richard Irwin’s Reel Radio online aircheck archive moved from a free to paid subscription service in 2006 to cover server costs, and by 2010 had nearly doubled its fees to meet increased operating expenses that Irwin attributed to “[listener] attrition, lack of corporate support and ongoing theft and trade of our exhibits.”

Online services are also directly impacted by the formal economies of official copyright regulation; Dale Patterson’s Rock Radio Scrapbook collection announces on its front page that “Rock Radio Scrapbook pays music licensing fees to the Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada,” while the growing popularity of Irwin’s site has made it a target of an RIAA crackdown that leaves the legality of many similar services in the U.S. in serious question.

Understanding the forces of capital that shape and limit the amateur archive is a necessary condition for effective dialogue between official and unofficial keepers of cultural memory, while raising concomitant policy issues that directly impact prospects for broader public access to archived materials.

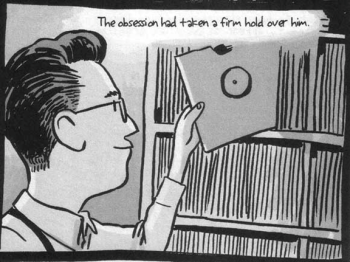

3. Libidinal Economy (From Bootlegger to Ragpicker)

In his book on the late Orson Welles, Joseph McBride cites a 1981 talk in which Welles proclaimed, “I’m an amateur director . . . in the sense that ‘amateur’ derives from love.” This libidinal economy of amateurism, applied to collecting, moves us from the figure of the bootlegger to Walter Benjamin’s ragpicker, who strives to rescue the detritus of mass culture from destruction. In what sense may these salvage missions be characterized as labors of love?

Speaking with collectors, tales abound of last-minute rescues of master tapes discarded or on the brink of destruction by station owners who failed to see their value. As Benjamin says in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” “every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.” The collector here appears as the final bulwark against otherwise inexorable forces of historical destruction and amnesia, the hero in a desperate scene of object-rescue.

In his work on collecting and consumerism, Russell Belk argues that efforts to save the object are often acts of love, but a love of two kinds: agape, that “selfless love” in which the collector gives himself over to the object, and eros, in which the object forms the screen for the collector’s own projections and desires. The amateur archive is suspended between these two loves.

Agape relinquishes the object in the very act of saving it and may better facilitate its reinscription within a new order of the official archive. However, it may also produce an indiscriminate antiquarianism that levels differences in meaning and complicates prioritization for preservation purposes, making all objects equally important and worthy of saving.

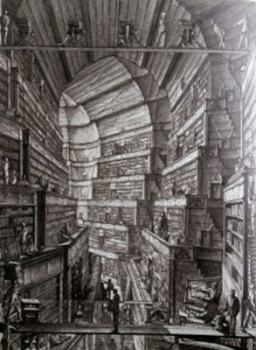

Eros rescues the object from antiquarianism but may also trap it within the collector’s own private echo-chamber, yielding not a Library of Babel so much as a Wunderkammer whose secret code must be broken before its materials can be extracted and made usable for other forms knowledge-production. Eros bears within it the seeds of critical history, in its selective cutting-up and rearrangement of the past, but it may also foster a possessive individualism whose hold cannot be easily broken. We must learn to recognize which is which.

Closing Thoughts: The Noble Amateur?

In analyzing the informal economy of the amateur archive, we should take care not to replicate the myth of what Andrew Keen has called “the noble amateur.” While I do not share Keen’s views about the amateur’s destructive impact on creativity and professionalism, knee-jerk valorizations of bottom-up modes of cultural praxis should indeed be questioned, along with their presumed opposition to forms of top-down institutional power. Amateur archivization includes a broad range of practices (some valorous, others not), while efforts to open exchanges between amateur and official archives are ill-served by placing them in a relationship of a priori opposition.

The category of the “amateur” is itself problematic, blinding us to the expertise of the individuals involved – who often have extensive training as professional sound workers and web workers, may be published authors, and in some cases even hold part-time academic appointments. The “amateur” designation may here prove a problematic othering strategy that absolves us from the difficult work of interrogating the foundations and authorizing forces of “official” histories and archiving institutions. Creating effective dialogue between official and unofficial sites of cultural memory is essential for achieving the RPTF’s long-term goals of preservation and public access, but success in this area requires understanding the component economies of the amateur archive and critical questioning of the institutional forces that for too long have rendered it mute and invisible.

Image Sources:

1. QRL Card

2. Radio Shack Cover

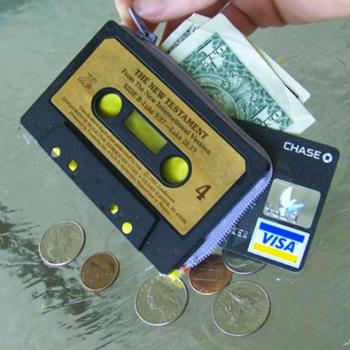

3. Cassette Wallet

4. Ragpicker

5. Library of Babel

6. Anatomical Cabinet

7. Boris Rose