I Am The One Who Acts: Breaking Down Bryan Cranston’s Breaking Bad Performance

R. Colin Tait / Texas Christian University

– Vince Gilligan1

Acting is not commonly discussed in relation to television. More often than not, television acting, and by proxy, television actors, has been viewed as inferior to film, which is more often associated with prestige. Although TV’s cultural value is on the upswing, perceptions about TV acting is still an under-examined subject, especially in latest era of great television. However, as Torben Grodal reminds us, scholars and critics are drawn to directors, while audiences relate to actors, dissertation writer and their performances.2

So, while TV may now be more cinematic, good acting is still what ultimately fuels the engine.

I offer Bryan Cranston’s universally lauded, multiple Emmy Award-winning performance in Breaking Bad as an intervention to this problem. By characterizing Cranston’s portrayal of Walter White as a “long-form performance text,” and concentrating on what is arguably the series’ most memorable moment – I propose an alternate method to consider television authorship and an actor’s contribution to the series. As Cranston’s five-season-long character arc from the nebbish White to methamphetamine kingpin “Heisenberg” is one of the most pronounced and vivid transformations in television history, I maintain that it can consequently be utilized to read moments of agency and labor that Cranston brought to his role.

Only by considering Cranston as a complementary author to showrunner Vince Gilligan can we understand how he shapes the series, and how actors function within television more generally. The question remains: how do we quantify Cranston’s performance of research papers as Walter White? Without direct access to his script pages, there is little room for such analysis of the actor’s interpretation, not to mention the difficulty of translation from the script page to the screen. Moreover, how is Cranston’s performance shaped by his fellow actors, including multiple Emmy-winning performers Aaron Paul and Anna Gunn.

Inspired by Cynthia Baron and Sharon Marie Carnicke’s analysis of “character interactions” within The Grifters (Steven Frears, 1990) I will analyze Breaking Bad’s most famous monologue3 . Next, I will illustrate the scene’s context in order to account for the shifts within it. I will also position this scene within the rules of classical tragedy, where the protagonist makes a fatal decision that ultimately leads to his downfall. Finally, I will analyze the scene as a performance within a performance, where Walt’s bravado in the scene is actually a sign of his weakness rather than his strength.

The “I Am The One Who Knocks” Scene

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31Voz1H40zI[/youtube]

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OuoZqLyMMI4[/youtube]

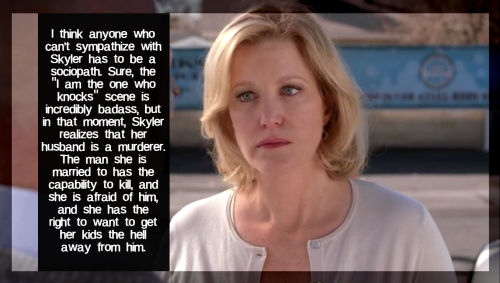

As famed acting guru Stella Adler once pronounced, all “acting is reacting.” One reason that this scene is so memorable is because of the skillful work of Anna Gunn as Skyler White. While Cranston may score the goal in this particular power play it is only because he gets a great assist from his scene partner. So despite this scene being more famous for Cranston’s monologue, it is his scene partner Gunn who anchors the action and has the more difficult role of reacting to Walter’s bravado.

Indeed, as Cranston relates in the following clip, the scene takes place at Walt’s complete transformation into Heisenberg as he reveals his tragic flaw.

Dramatic irony also comes into play here. What the audience knows and Skylar doesn’t is that Walter’s speech is itself an act, very much calculated in order to silence his wife on the subject. So, despite Walter’s protestations to the contrary term papers, what is clear in the scene, is that he is actually in a much more precarious position than he is indicating here — making this a violent performance within a performance.

Moreover, what the scene ultimately reveals is that Walt’s superpower is not his ability to cook crystal meth better than anyone else, but, in fact, it is the power of his performances and his ability to lie convincingly. In other words, he is an actor of the highest order, and much of his empire is built on theatre — the main source of his power.

There is also the question of whose scene this is. Since it begins and ends with Skylar, I would argue that it is actually hers. Again, following Adler, her reactions to Walter’s bravado are crucial to the way the scene plays out. Taken as a whole, we see a classic staging of the transfer of power. It is also a demonstration of extreme violence under the surface and from here, Skylar is basically cowed into submission by Walter’s display. I would also state that what is unsaid is as important as what is being said and the subtextual dimension (what is neither spoken nor heard within the scene, but is clearly going on in Skylar’s silence) speaks more effectively than Walter’s monologue does. Here, the acting is combined with editing to register the contrast between Walter’s madness and Skylar’s growing anxiety.

Conclusions

Within this short piece, I have demonstrated that television acting needs to be taken seriously within the context of television’s commercial and critical resurgence. Only by examining Walter White’s famous monologue in relation to the character it is spoken at, and within the series-long character arcs that Cranston, Brandt and Paul perform in, can we productively come to conclusions at https://grademiners.com/lab-report about the state of contemporary TV. What I offer here is merely a snapshot of the kinds of methods that could be employed if critics and scholars are to effectively understand some of the overlooked elements that are largely responsible for the current ascension of Television’s “Quality.”

Image Credits:

1. One Who Knocks

2. Danger

3. Skylar

Please feel free to comment.

- Quoted in Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution: From The Sopranos to Mad Men to Breaking Bad, p 265. [↩]

- See Grodal, Torbin “Introduction” in Grodal, Torben K, Bente Larsen, and Iben T. Laursen. Visual Authorship: Creativity and Intentionality in Media. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, University of Copenhagen, 2005. Print. [↩]

- see Baron and Carnicke “Stanislavski: Player’s Actions as a Window into Character’s Interactions” and “Case Study: The Grifters” in Reframing Screen Performance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008. Print. pp 208-230 [↩]

- See Gray, Jonathan, Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. New York: New York University Press, 2010. Print. [↩]