Reconsidering the Technological Limitations and Potential of Large Format

IN ADDITION TO OUR REGULAR COLUMNISTS AND GUEST COLUMNS, FLOW IS ALSO COMMITTED TO PUBLISHING TIMELY ONE-TIME COLUMNS, SUCH AS THE ONE BELOW. THE EDITORS OF FLOW ARE TAKING SUBMISSIONS FOR THIS SECTION. PLEASE FEEL FREE TO CHECK OUT OUR LATEST SUGGESTED CALLS FOR CONTACT INFORMATION.

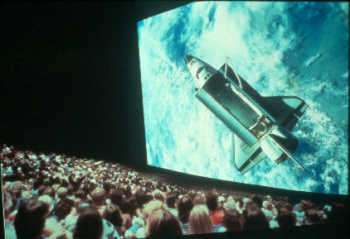

Shuttle on IMax

The first large format film, Tiger Child, was screened at Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan, and was the culmination of innovations in film, camera, projector and screen technologies. Shortly after the film’s premiere, Roman Kroiter (1970, 799), one of the founders of the IMAX Corporation, was quoted as saying that “Artistically it will have to be breaking through new frontiers, not the millionth re-hash of the same old cliches. The world isn’t going to stand still, and the movies won’t either.”

Today, as then, this largest of film formats offers incredibly high-resolution images that make the viewer feel like they are part of the action. However, some would argue that large format films have not achieved the full expression of their technological potential, primarily as a function of the format’s association with educational facilities such as museums and science centers, where the emphasis is on creating an educational film, not a film that extends the potential of this medium. The need of museums to sell film tickets — as these theatres are often much-needed sources of operating revenue — means that the content of large format films must align with consumer needs and the museum’s mission statements. This historically limited market niche for large format films also means that filmmakers’ products must be acceptable for the distinct market segment represented by the museum visitor. Artistic films, that is, films that stretch the boundaries of what is normal and acceptable to the majority of viewers (either through content or technological innovation), are not considered to be films that will attract an audience of schoolchildren and educators.

Museums have thus served as gatekeepers for the large format film, providing feedback regarding the films in order to maximize profits and to meet their obligations for informal education. Fueled by the fact that “the quest for audiences in order to recoup capital investment has meant that achieving the real has tended to privilege the more real than real, the “realistic” (Wollen, 1993), themes of nature, travel, and broad themes of science and exploration have dominated and continue to dominate the large format film lexicon. Films that fall outside of these categories, which are sometimes the most popular films (in dollar terms, and generally those that have been repurposed from 35 mm) are not always selected for showing, or are shown only after closing hours as their themes are not mission-based. The choice of films shown may also be limited to those which don’t conflict with the particular audience’s foundational beliefs, as occurred when the film Volcanoes of the Deep Sea was not shown in certain museums due to its reference to evolution (Dean, 2005).

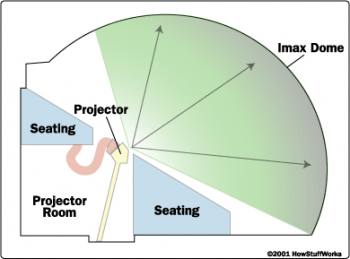

Much has also been written of the limitations of the technology due to issues with cassette length (the canister that holds the raw film), lighting needs, projected image size, and screen shape (films may be shown on either domed or flat screens, up to 80 feet high); all of which have been used as justification for creative decisions related to the structure of these films. It is believed by many filmmakers that close-ups, shot/reverse-shot and other editing conventions are impossible within the medium due to these issues. Panning is avoided in large format, and medium or long shots dominate as there is not only concern that the sight of an 80-foot human face would be disconcerting, but that the intense lighting required for such close-ups “make actors irritable” (Sherrill, 1983). Shots are paced at longer intervals in order to allow time to assimilate visual information, which in turn affects the acting, dialogue and emotion needed for dramatic scenes (Wollen, 1993). Narrative action is thus limited to point of view shots and composition within the frame, which take the place of the rapid cuts and sequential juxtaposition common to the traditional 35 mm film (Wollen, 1993).

IMax Theater

But the example of films such as Pulse: A Stomp Odyssey, would seem to indicate that the perceived need to create educational films in a particular style — and not technological limitations — has been the major force in limiting the full expression of the potential of the large format film. Without words, this award-winning film uses images to tell the story of sound and rhythm. Extensive use of close-ups loosens the boundaries of what have been considered inviolate limitations in the large format. These close-ups are not only effective in conveying the film’s message of diversity and rhythm, but demonstrate that the technological limitations of large format may be perception and not reality, especially since the filmgoing audience has expressed appreciation for the film through their continued attendance.

But can one promote innovation in large format when filmmakers are still to a great extent obliged to the needs of the museum industry for educational films? It may be that today such a shift is happening to the industry, not necessarily by the industry. The development of stand-alone large format theaters, combined with the digital remastering (DMR) of 35mm Hollywood films into large format, is shifting the concept of large format away from the museum-based educational experience towards an entertainment experience, which has greater possibility for innovation and experimentation. These shifts would appear to allow large format to fulfill the new visual frontiers as predicted by Roman Kroiter.

However, the remastering of films begs the question as to what exactly is large format, and what differentiates it from other film formats? Predicated on a particular quality and size of image, the remastering of Hollywood films into large format means that the unique characteristics of this medium are lost in — so to speak — translation. Although DMR technology restores the filmic structures that have been avoided or eliminated in the creation of a large format film, allowing for greater latitude for experimentation in filmmaking, this translation also eliminates the uniqueness of the large format camera and film and its attendant effect on the capture and display of the “all-engulfing, panoramic images” (Acland, 1998, 434) on which the format is based. These changes may open the possibility for the extension of the large format technology, but they may eliminate the uniqueness of the medium of large format; that is, once we can define exactly what is large format.

References:

Acland, C.R. “IMAX Technology and the Tourist Gaze.” Cultural Studies 12.3 (1998): 429-45.

Dean, C. “A New Screen Test for Imax: It’s the Bible vs. the Volcano.” New York Times. 19 March 2005.

Kroiter, R. “IMAX at Expo 70.” American Cinematographer 51.8 (1970): 772-99.

Sherrill, N.H. “Behold Hawaii.” American Cinematographer, 64.12 (1983): 62-67.

Wollen, Tana. “The Bigger the Better: From Cinemascope to IMAX.” P. Hayward and T. Wollen, eds. Future Visions: New Technologies of the Screen. London: BFI, 1993.

Image Credits:

2. IMax Theatre

Please feel free to comment.

This is an excellent piece on the institutional and creative limitations put on technology. These processes are not only affecting the quality but also the distribution of a number of IMAX films. I personally believe that IMAX technological limitations will soon be overcome grace of scientific progress. However, the greatest threat is museum gatekeeping role and silencing of artistic creativity. In this regard, Nucci’s point is well taken: for people interested in artistic freedom and IMAX, this is not a time to roll over and play dead.