Text-To-911: Disability Accommodations, Universal Benefits, and Telecommunications Legacies Elizabeth Ellcessor / Indiana University

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z_OTORD4rx0[/youtube]

My home state of Indiana was the second to widely implement text-to-911 (following Vermont). This was made possible by INdigital telecom, which manages Indiana 911 services, routing calls on behalf of the Indiana Wireless Enhanced 9-1-1 Advisory Board. In May 2014, INdigital launched texTTY for use in 911 call centers. Indiana PSAPs now have access to texTTY, “a platform that allows the PSAP to ‘add on’ non-voice (SMS)”1 to an existing call. This means that PSAP workers can receive texts and reply, as seen in the video below, using a simple interface; they may also choose to initiate texts following a silent phone call from a given number.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EqjPDLNX8aI[/youtube]

In the case of Indiana, according to the Indianapolis Star,3 text-to-911 “will let Hoosiers call for help with the same amount of effort it takes them to “LOL.”” It may be possible for me to alert emergency services with a quick “OMG,” but the rollout of this service has been accompanied by constant exhortations that members of the public avoid using it. The FCC advises that “texting to 911 should be thought of only as a last resort, …. people who are hard of hearing, deaf, or speech-impaired should still be encouraged to use TTY for calling when they can.”4

In short, text-to-911 in Indiana was introduced primarily as a benefit for those in situations in which speaking would be unsafe, and as an accommodation for people with hearing or speaking impairments. Indiana is estimated to have nearly a quarter million d/Deaf residents, and Barry Ritter, executive director of the state 911 Board explained to the Indiana Daily Student that “It was our focus that the sooner we could begin offering text-to-911 services at https://grademiners.com/book-report, we would be providing equal access to the deaf and speaking-impaired.”6

The emphasis on direct access to emergency services for d/Deaf and speech-impaired individuals is laudable as a means of extending access to telecommunications media. Certainly, this is an improvement on the retrofitting of technologies and services that has historically characterized access to media by people essay writing with various disabilities.7 Wentz, Jaeger, and Lazar argue that such retrofitting is encouraged by disability laws, which offer numerous exemptions and rely upon individual complaints for enforcement, thus offering very little incentive for policymakers or media industries to consider disability needs prior to the development of new media forms or technologies.8

“Universal design” offers a more inclusive approach, which would take into consideration the needs of people with disabilities or other non-normative bodies or needs in the development phase of new technologies or structures.9 One of the benefits of universal design, dating back to its origins in architectural fields, is that it produces benefits for all users. For instance, curb cuts help wheelchair users and are also beneficial for people using strollers, dollies, or on roller skates.

The instructions offered by texTTY are illustrative in this regard:

“Select ‘create a new text message’. Put 911 in the to: field. Put your emergency and your location in the message body. Do not attach or send pictures or videos. Keep your message short and do not use abbreviations.”10

In the interests of simple implementation, images, videos, emoji, abbreviations, and other standard elements of contemporary text messaging culture are expressly forbidden. It is unclear what, exactly, would happen were a PSAP to receive a text message featuring an image of illegal activity. Yet, this might easily be the first impulse of a user – d/Deaf or hearing – sending a text from a tense situation in which typing a longer message could attract attention. Even as the spelling of Indiana’s “B4 U TEXT” public service announcements acknowledges that texting involves unique cultural literacies, the expectations of emergency call centers (and their technologies) rely upon standard written communication or equivalence with spoken messages.

Finally, text-to-911 fails as an example of universal design in its limited, and gradual roll-out. Mobile devices are increasingly central to daily life; the Pew Internet and American Life Project reports that roughly 90% of adults own a cell phone, and 81% of adults use their cell phones to send or receive text messages.11 These numbers are fairly consistent along racial demographic lines, and vary only slightly by urban or rural location. Yet, in Indiana, it is the urban and more racially diverse cities of Indianapolis and Gary that are lagging in implementations of text-to-911. Even in Bloomington, there was concern about the unknown volume of texts that could be received in a town with a large undergraduate population, resulting in a slight delay in implementation. Thus, in areas that might be expected to have high demand for these services, there is little availability, likely leading to a depression of awareness and use that may persist long after text-to-911 services become fully operational and work against the inclusive benefits of such a technology.

The potential benefits of text-to-911 are enormous, for people with and without disabilities and in a variety of contexts. Yet, instead of functioning as an exemplar or universal design, text-to-911 looks to be hampered by its historical roots in landline technologies, its lack of cultural flexibility, and its attempts to discourage use of this service outside of specific cases. Though there are practical concerns to implementation, the narrowness of text-to-911 seems likely to limit its utility rather than to enable a real advance in telecommunications capabilities and relevance.

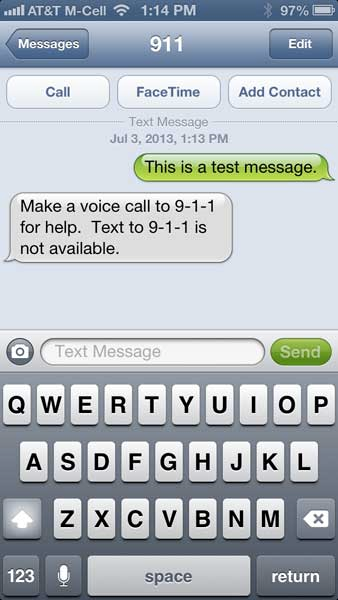

Image Credits:

1. “American Voices: FCC Mandates Text-To-911 Emergency Service,” The Onion, August 12, 2014, http://www.theonion.com/articles/fcc-mandates-textto911-emergency-service,36672/.

2. “Wireless Carriers Meet a Text-to-911 Deadline,” Dispatch Magazine On-Line, July 3, 2013, http://www.911dispatch.com/2013/07/03/wireless-carriers-met-a-text-to-911-deadline/.

Please feel free to comment.

- “texTTY,” texTTY, n.d., http://www.textty.com/. [↩]

- “Best Practices for Implementing Text-to-911,” FCC.gov, February 24, 2014, http://www.fcc.gov/encyclopedia/best-practices-implementing-text-911. [↩]

- Justin L. Mack, “Text-to-911 Service Unveiled Statewide,” Indianapolis Star, May 14, 2014, http://www.indystar.com/story/news/crime/2014/05/14/text-service-unveiled-statewide/9081155/. [↩]

- Jessica Dolcourt, “Text-to-911: What You Need to Know (FAQ),” CNET, May 5, 2014, http://www.cnet.com/news/text-to-911-what-you-need-to-know-faq/. [↩]

- Brian Fung, “911 for the Texting Generation Is Here,” The Washington Post, August 8, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-switch/wp/2014/08/08/911-for-the-texting-generation-is-here/; Dolcourt, “Text-to-911.” [↩]

- Javonte Anderson, “Indiana One of First States to Introduce Text-to-911,” Indiana Daily Student, May 18, 2014, http://www.idsnews.com:80/article/2014/05/indiana-one-of-first-states-to-introduce-text-to-911. [↩]

- Gerard Goggin and Christopher Newell, Digital Disability: The Social Construction of Disability in New Media, Critical Media Studies (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003). [↩]

- Brian Wentz, Paul T. Jaeger, and Jonathan Lazar, “Retrofitting Accessibility: The Legal Inequality of After-the-fact Online Access for Persons with Disabilities in the United States,” First Monday 16, no. 11 (November 5, 2011), doi:10.5210/fm.v16i11.3666. [↩]

- Ronald L. Mace, Graeme John Hardie, and Jaine P. Place, Accessible Environments: Toward Universal Design (Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University, 1990). [↩]

- “texTTY.” [↩]

- L. Street et al., “Mobile Technology Fact Sheet,” Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, accessed January 12, 2015, http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/. [↩]

Your post draws important attention to communication and access, and it reminded me of this recent incident in Kansas City: http://www.kctv5.com/story/279.....eck-victim.

Particularly problematic is how American sign language is alternately described in the article and the video as a “special talent” and “difficult to learn”–not to mention how the paramedics were “dumbfounded” by the child’s ability to use ASL. Emergency services’ inability to fully serve the local community should draw more concern than wonder.

At least the mother’s comments are more progressive and inclusive.