Binders Full of Women: A Feminist Meme to Bind them All

Samantha C. Thrift and Carrie A. Rentschler / University of Calgary and McGill University

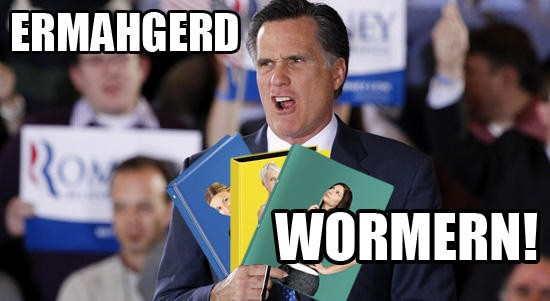

Social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr, as media reporter Virginia Heffernan put it, “don’t blow up for no reason.”1 On October 16, 2012, the Internet exploded with humorous visual image macros in response to Republican U.S. presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s answer to voter Katherine Fenton’s question regarding women’s pay inequity during that evening’s televised presidential debate, to which he replied: “I went to a number of women’s groups and said: ‘Can you help us find folks,’ and they brought us whole binders full of women.” Many people (including the authors of this piece) turned to social networking sites to share their chagrin at his seeming disregard for women as voters, workers, and fellow human beings.

The meme Binders Full of Women quickly manifested in image macros and gifs, as a Tumblr, a Facebook page, and mock customer reviews for three-ring binders sold on Amazon.com. By appropriating consumer spaces, curating image macros, and posting to Facebook, feminist meme creators and distributors responded to Romney’s gaffe and other more egregiously misogynist Republican claims making in political debates about sexual violence and women in the work place in 2012, amplifying, nearly instantaneously, a network of feminist political critique that seemed to rise up from the screen, standing in relief against popular claims of U.S. feminism’s decline and death.2 Binders Full of Women revealed a set of humorous practices for doing feminism via peer-to-peer social media platforms and micro blogs, through which the political humour and critique they foster can spread. Whitney Philips and Kate Miltner argued that the “political memesplosian” accompanying the 2012 American election campaign was hardly surprising, since “memes (and meme creation as a cultural practice) have become mainstream.” The question, they suggest, is not “‘will there be memes’ but ‘which memes will they be’.”3

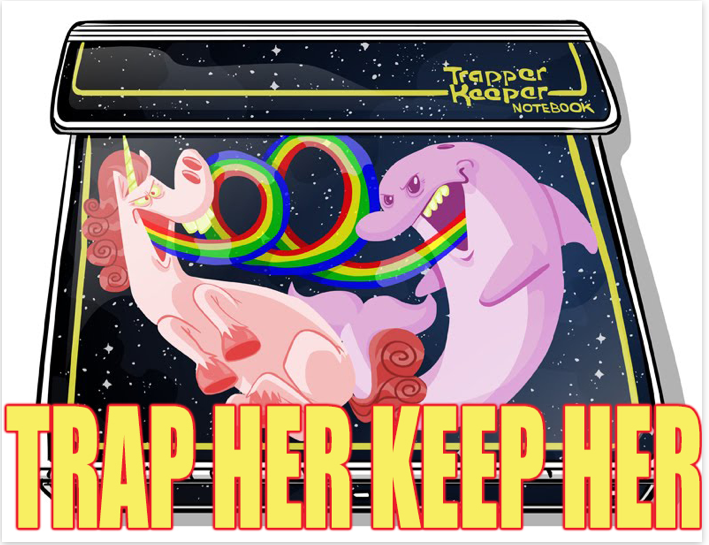

On the night of the debate, Veronica DeSouza created the Tumblr Binders Full of Women, where, within 24 hours of establishing the site, over 200 image macros were posted in response to Romney’s quip and 11000 people began following the Tumblr microblog.4 The first image macro posted on Veronica DeSouza’s Tumblr Binders Full of Women appeared at 9:48pm the night of the debate. The joke, “Trap Her Keep Her,” drew on the popular 1980s student binder brand Trapper Keeper for its graphic art, bright colours, cartoon animals and Velcro closure.

The Binders Full of Women Facebook page also appeared the night of the debate, created by page administrator Michael M Fil from Toronto, Ontario. Fil moderates the page to cultivate a safer online space for “[t]alking about current events, politics, gender issues, privilege, memes, etc”, explaining that, if a comment or post is deleted, “[i]t was probably […] because you used a slur, trolled, or attempted to derail a discussion. Sometimes, Facebook comments disappear and I don’t know where they go. Possibly Narnia.” In an early example of the phenomenon of writing funny mock reviews of products on Amazon.com, the day after the debate on October 17, 2012, an Amazon.com reviewer named Bazinga posted a satirical review of the Avery brand durable view binder with 2-inch slant ring, asserting “I don’t want to be filed away in an inferior & confusing electronic doohickey that I couldn’t possibly understand,” poking fun at the ways women are often cast as technologically illiterate. Over 13000 Amazon.com site users ranked Bazinga’s review as “most useful.” One reviewer jokingly commented on how efficiently the product binds women: “not my feet, just my brain,”5 while another described the tactic of mock reviewing as “some of the best crowd sourced comedy we’ve seen in a long time.”6

In the run-up to the 2012 U.S. election, feminist memes about gender inequality in the workplace, access to abortion, and the language of rape, moved women’s issues into a prime spot on the campaign agenda. This capacity to respond constitutes an engagement of feminist subjectivity based in social media networks of distribution, what we call “doing feminism in the network.” If, as Janet Bing argues, the Internet is particularly good at facilitating the diffusion of feminist humour online, the networking, linking and distributive capacities of Twitter, Facebook and Tumblr also create new modes of feminist cultural critique and models of political agency for doing feminism in ways that are especially timely.7

A feminist meme event, we suggest, is a form of feminist media event that references not only an external event like a U.S. presidential debate, but soon becomes a temporal signpost that references response speed and an emerging context of feminist criticism.8 Several posters reflected on the timeliness and public nature of their response. On the Facebook thread, the third comment reads, “that was quick” (posted at 22:11 on October 16, 2012, the night of the debate), followed in rapid succession by: “I love how quickly this page was created” (22:17), “I love how many likes it already has LOL” (22:18), “I can’t believe how fast this page came out!” (22:20), “Hysterical!! How fast did this get done?” (22:20), “This page was created 40 minutes ago” (22:23), and “oh how quickly this web moves” (22:25), “Wow, just wow, at both the comment and the speed of this page and the speed of the likes” (23:24), and “How is there already a Facebook page for this?? lol” (23:40). Commenters observed the speed and virality of the new meme, with posts that tracked the growing number of “Likes”: “55,000 Likes in ONE HOUR. I’m impressed” (22:50), “112K Likes in 1 hour…Wow!” (23:35), and “Created NINE hours ago and over 222 THOUSAND likes … yes…this resonated deep and wide” (October 17, 2012). Meta-commentary focused on the speed of posting and page “Likes” takes shape itself as an event, a thing to talk about and participate in – a way of temporally registering the ability to quickly respond to political debate.

Similarly, in the comments linked to the Binders Full of Women Facebook cover image of a row of rainbow-coloured binders, early posts also evidence a sense of excitement derived from “meme spotting”: “YES THIS IS A THING. Internet, I knew you’d never let me down” (Coral Rose, 16 October 2012) and “Words cannot explain how unbelievably awesome this page is. Oh Internet, I knew you’d never let me down” (Janey Marie Thomas, October 17, 2012). The comment thread revealed a shared instinct to document individual experiences of incredulity, anger, and general “WTF-ness” evoked by Romney’s anachronistic sexism: “Binders? Binders? What decade is this guy living in? Flash drives … maybe. Binders are SO Boogie Nights” (Don Young, 17 October 2012), “What the hell did he even mean by this???? So weird. So weird” (Britt McNiff, 16 October 2012), “Yeah this was the comment that really got me shaking!” (Molly Schissler, 16 October 2012), and “I posted on a friend’s wall ‘Binders full of women…I’d like to have been a fly on that wall’ right after his comment […]” (Kelly Waterman, 16 October 2012).

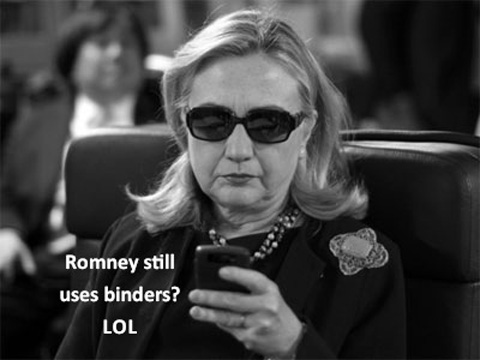

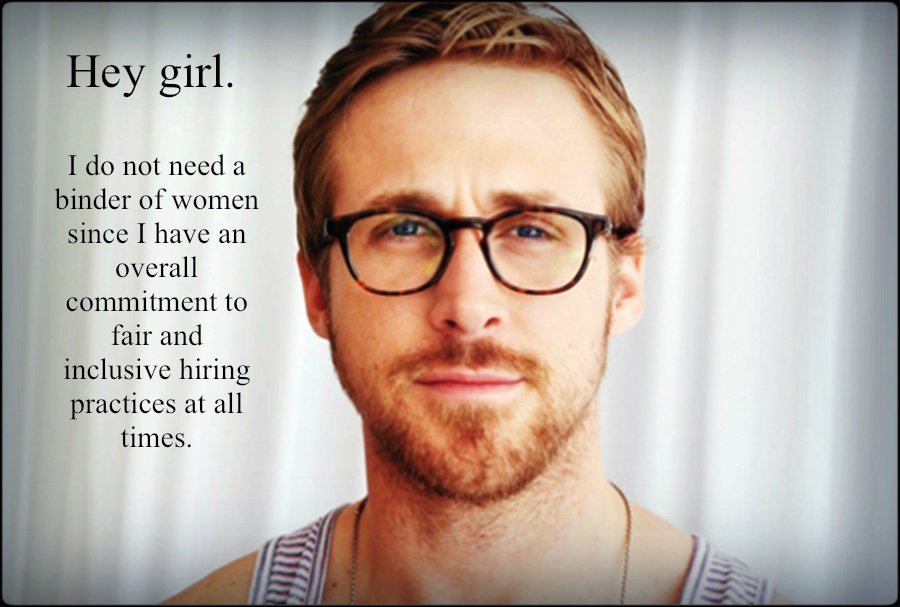

The meme Binders Full of Women manifested a networked public whose discourse was explicitly feminist. It was diffused to strangers as part of a larger imagined collectivity (“connections forged among strangers,” as Michael Warner describes them) enabled by social media, and because of its temporality of circulation, its “punctual circulation…turns [discursive] exchanges into a scene with its own expectations.”9 Participants brought an expectation of humour to the scene of public discourse. Their trade in jokes and criticism signalled the ways in which people responded to the sexist tone and content of election discourse through feminist humour. Binders Full of Women inter-textually referenced several other memes in a moment of meme amplification, including Texts from Hillary, Feminist Ryan Gosling and Inappropriate Timing Bill Clinton.

Feminist use of Internet meme warfare and other forms of new media disruptions to what Sara Ahmed describes as the feminist killjoy stereotype expose a feminist hack value of playful and political exchange that is mobilized rapidly and picked up by online aggregators, in ways that make visible feminist networks of response and resistance in some unexpected online spaces.10 Binders Full of Women represented a shared space of public discourse that propagates feminist humour. That propagation makes visible a diverse and ambiguous understanding of feminism expressed in practices of meme aggregation, compilation, and replication. While different image macros revealed different articulations of feminist critique, comments on the Facebook page also suggested that the turn to feminist humour illuminated rifts in feminist sensibilities about how best to respond to Republican backlash against women. One Facebook post scoldingly calls for civil discourse and feminist civic-mindedness the day after the televised debate:

Instead of personal attacks, let’s try a bit of civilized discourse. Rebut with facts. Cite sources. What are the candidates’ track records on helping to close the wage gap? What are the candidates’ track records on women’s rights in general? What more can be done by both parties? (October 17, 2012)

While this post called for feminist seriousness in the wake of the debates, others used humour to articulate a form of feminist critique that was especially mobile across social media sites, changing up the terms of debate in part by poking fun and making jokes, as this sarcastic Facebook post from November 1, 2012 illustrates:

So, let me get this straight: according to some Republican candidates, forcing a woman to carry her rapist’s baby to term is OK, but federally mandating paid maternity leave is a no-no? What about automatically denying the rapist custody of the child? Also no? Super.

Based on a review of posts in 2014, posts to the Facebook page discuss current U.S. politics, Clinton’s potential run for the U.S. presidency, state passage of gay marriage laws, and gender issues on the Internet.11

The feminist memetics of Binders Full of Women still resonate today alongside other durable gender memes like Texts from Hillary. Such memes “with a feminist lean” look to be key features of electoral campaigning for Clinton. #ReadyforHillary, a PAC campaign for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run, repackages 2012’s “meme of the year” Texts from Hillary in its materials. In June 2014, CNN reported that Texts from Hillary “humanized” Clinton as a candidate in the now ubiquitous photograph of her scowling at her mobile screen behind dark sunglasses.12

Heading into the 2016 U.S. federal elections, we will see how the Binders Full of Women meme re-visits the American political scene, particularly in a context where a Clinton presidential run would set the Democratic party’s visible, if still largely symbolic, commitment to gender equity in high relief against the Republican party’s ongoing “war on women.”13 Binders Full of Women endures as more than the GOP’s political albatross. In addition to the vital Binders-themed feminist networks of critique the meme inspired, the meme persists in the political memory of other countries,14 and often circulates as a cautionary tale in news reports, such as the deputy prime minister of Turkey’s admonition that women should not laugh in public.15 In this light, the so-called end of a feminist meme may in fact be more of an assertion or aspiration than a guaranteed practice. One cannot simply “close the binder,” so to speak, even if one declares it to be over.

Image Credits:

1. Romney

2. Trap Her Keep Her

3. Texts From Hillary

4. Feminist Ryan Gosling

5. #ReadyForHillary

6. @TheHillaryBus

Please feel free to comment.

- Virginia Heffernan, “Presidential Jingles and Sympathy for the Loser.” Studio 360 radio interview (November 2, 2012). [↩]

- Jen Pozner, “The ‘Big Lie’: False Feminist Death Syndrome, Profit, and the Media” in Rory Dicker and Alison Piepmeier (eds) Catching a Wave: Reclaiming Feminism for the 21st Century (Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 2003), 31-56. [↩]

- Whitney Philips and Kate Miltner, “The Meme Election: Clicktivism, the Buzzfeed Effect and Corporate Meme-Jacking.” The Awl (November 2, 2012). [↩]

- Veronica DeSouza, “It’s Time to Close the Binder.” Binders Full of Women Tumblr (November 7, 2012). Leslie Kwoh, “Binders Full of Women’ May Help One Woman Get a Job.” Wall Street Journal (October 17, 2012). [↩]

- LeeBo, “Wow I feel Secure.” Amazon.com customer review (2012). [↩]

- Madeline Davies, “Amazon Customers Go Rogue, Hilariously Review Bic’s Idiotic Pen for Women.” Jezebel (2012). [↩]

- Janet Bing, “Liberated Jokes: Sexual Humour in All-Female Groups.” Humor 20:4 (2007), 337-366. [↩]

- Samantha Thrift, “Feminist Eventfulness, Boredom and the 1984 Canadian Leadership Debate on Women’s Issues.” Feminist Media Studies 12:3 (2012), 406-421; see also Samantha Thrift, “#YesAllWomen as Feminist Meme Event” Feminist Media Studies (2014). [↩]

- Michael Warner, “Publics and counter-publics.” Public Culture 14:1(2002), 66. [↩]

- Sara Ahmed, “Killing Joy: Feminism and the History of Happiness” Signs 35:3 (2010), 571-594. [↩]

- See Binders Full of Women FaceBook page and Vogue [↩]

- See Brandon Griggs, “What Clinton Says, Clinton Memes.” CNN (June 17, 2014). [↩]

- See Dailykos.com and Salon.com [↩]

- See TheGuardian.com and Irishexaminer.com [↩]

- See Nationalpost.com [↩]