Oh Snap! Stop Shaming the Sext Jacqueline Ryan Vickery / University of North Texas

When it comes to online privacy, I commonly hear some version of, “Well, if they didn’t want anyone to see it, then they shouldn’t have put it online.” Such a simplistic approach may be justified when we consider, say, deliberately sharing a supposedly inappropriate photo on a non-private Instagram or Twitter account. However, the attitude becomes deeply disturbing when applied to blatant breaches of privacy, for example, revenge porn sites1 and the recent hack of a third-party Snapchat app.2 In both of these instances, images were distributed in contexts outside of the original context in which they were shared, and importantly, they were shared without the consent of the individuals in the photos. Transmitting content outside of its intended context is a clear breach of privacy, what Nissenbaum (2004) refers to as a breach of “contextual integrity”. Yet, rather than blame those violating privacy, I continually encounter attitudes that blame people for sharing the photos in the first place. Such rhetoric is undoubtedly familiar to women, who are continually blamed for their own victimhood in cases of harassment, rape, and abuse. Hence, my frustration with an attitude that blames individuals (and namely women and youth) for sharing “inappropriate” photos in the first place.

Such attitudes are part of a broader context in which women’s and young people’s practices are often trivialized, demonized, and pathologized. This is evident in the ways news media and popular culture continually seek to identify and name young people’s practices in order to position them as abnormal or extraordinary (e.g. cyberbullying, sexting, selfies, etc. Newsflash, teens don’t call it sexting, they just call it sending photos). Despite research that continually evidences the positive, empowering, smart, and creative ways teens use social and digital media, there remains a pervasive attitude of “kids these days, when will they learn?”. For example, Naked Security, an award-winning computer security news website, recently ran an article about the Snapchat hack. Rather than framing the issue for what it was (and what their site purports to be about) – a breach in security – they begin with, “What would it take to pry Snapchat out of the hands of college age users? Heaven knows, given that nothing’s worked so far.” There is absolutely no explanation of why we should want to pry Snapchat out of their hands – just an assumption that we should.

The recent Snapchat hack exposed the weakness of third-party apps and an overall vulnerability of online data. Of course, with recent breaches into supposedly secure systems such as Target and Home Depot, it’s likely Snapchat users are aware of potential security risks.3 But what this article (and so many like it) fails to acknowledge is the motivation for using apps such as Snapchat in the first place. Yes, young people (like adults) are concerned about security, but they’re also deeply concerned about social privacy – that is, privacy within and among their peers. As such, their use of Snapchat is often a deliberate strategy intended to maintain greater control of their social privacy. Social media render friendships, explorations, and interactions increasingly visible, searchable, and spreadable (boyd, 2010). For decades, internet scholars have been researching how young people’s identities and communities are mediated via technologies. Not surprisingly, there are a lot of positive reasons for and outcomes of using digital media to explore identity.

However, practices are also mitigated by negative consequences and unintended consequences. Reports demonstrates that young people are leaving Facebook (or at least using it less frequently) in favor of other social media platforms. There are a variety of reasons for this, not least of which includes concerns related to social privacy. Despite the fact that middle-class teens tend to consider their phones personal and private, it is not uncommon for peers to breach boundaries of privacy by looking through a friend’s phone without permission (Vickery, in-press4 ). For more working class teens, who often have limited or precarious access to mobile phones, it is not unusual for mobile devices (e.g. the iPod Touch) to be passed around and shared with trusted friends (ibid.). As such, young people are acutely aware of the risks of sharing intimate content at here https://grademiners.com/dissertation-help via social and mobile media (be it sexual or otherwise). Thus, Snapchat provides a viable alternative to traditional messaging apps and social media because it grants them greater social privacy. Regardless of whether or not the image can be stored on a server (or even saved via third party apps), the app minimizes the risk of someone inadvertently or deliberately viewing images, writing an essay on someone else’s phone. As Snapchat co-founder Evan Spiegel notes, “It seems odd that at the beginning of the Internet everyone decided everything should stick around forever. I think our application makes communication a lot more human and natural.” The ephemerality of the communication allows for greater social privacy and lends itself to intimate self-expression.

Furthermore, the rhetoric around intimate pictures falsely constructs the act itself as inherently inappropriate. In other words, sexually suggestive or nude photos tend to be discussed in terms of how “inappropriate” they are. Yet, when these photos are taken and shared within the context of a trusting and consensual relationship, there is nothing inherently inappropriate about them.5 However, the photos become inappropriate when they are shared in a different context – say one that is more public, professional, or with the intent to shame. But even then, it is not that the photo itself is inappropriate, but rather it is the sharing of the photo in a different context and without the consent of the individual that deems it inappropriate. We need to shift discourse away from discussing sexual and suggestive photos as inappropriate and abnormal, and rather focus on the inappropriate acts of sharing. This not only places blame back where it belongs – on those violating privacy – but also moves away from discourse that demonizes expressions of sexuality; instead we ought to approach sexually suggestive and explicit pictures as part of normal sexual expression, exploration, and intimacy.

We can continue to bemoan these “kids these days” (in which such rhetoric tends to lump all “millennials” together, typically the 35 and under generation) or we can start to hold the real perpetrators accountable – those who breach and exploit privacy, security, and social norms. Instead of telling young people the act of taking a suggestive or explicit photo is always “wrong”, we ought to shift the conversation to one in which we talk about when, where, with whom, and in what situations is it appropriate to trust and share intimately. And hold those who breach such norms responsible. No, this isn’t going to solve all the problems. But, it helps us move beyond discourses that continually position young people’s explorations as risky and devious.

And lastly, we cannot overlook the gendered implications inherent in these blatant breaches of privacy. Exposing a nude photo is undoubtedly a way to shame and harass the individual; it is a form of dominance and control in which the victim lacks agency over their own image (quite literally). While men are also likely embarrassed by a leaked photo, it is less likely to have the same long term effects on their reputation as it will for women. As Jennifer Lawrence responded after her nude photos were leaked, “I was just so afraid. I didn’t know how this would affect my career.” Revenge porn sites construct (women’s) bodies, sexuality, and agency as something to be controlled. And this is what further concerns me about the attitude of “just don’t take the pics in the first place”. The attitude further policies women’s sexual agency. It holds them responsible for violations of their privacy and victimhood, and erroneously distracts us from the actual harms, wrongdoings, and normative gender assumptions. Such rhetoric also calls into question about term papers discourses that continually construct youth as a risky and transgressive subject position. As Gabriel (2014) poignantly calls attention to, “If sexting, selfies and self-harm constitute unacceptable behaviours because they threaten the well-being, reputations and futures of young people, then the discourses used to make sense of these practices can (and ought) to be subject to critical interrogation” (p. 109).

I’ve been encouraged by some recent responses that are attempting to demystify the taboo around sexting. For example, the Everybody Sexts project tries to demonstrate the commonality, intentions, and normalcy of sexting. By soliciting narratives about one’s own sexting practices and then turning the photos into art, it helps to shift discourse away from risk and shame, and instead positions it as something that can be acceptable and normal in the right context (one in which the sender exerts control). I hope we can stop shaming people (namely women and young people) for expressing sexuality and instead work to create more normative values of privacy, alongside calls for greater data security.

Image Credits:

1. The Snappening: Snapchat Leaked Showcases Hacked Nude Photos

2. MyEx, A Revenge Porn Site

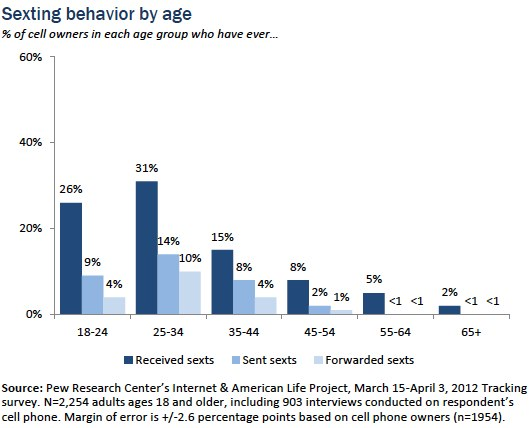

3. Sexting Behavior by Age

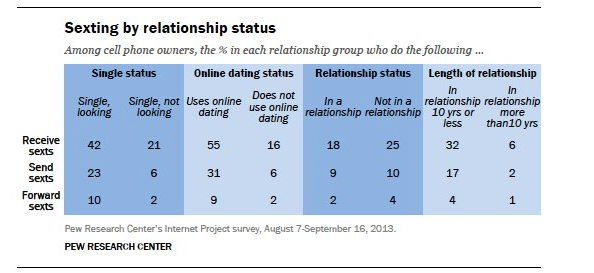

4. Sexting by Relationship Status

5. Meme about Online Leaking of Nude Pics

Please feel free to comment.

- Revenge porn sites distribute nude and/or sexually suggestive photos that have been submitted (usually by ex-lovers or scorned partners) without the consent of the individual in the photo. The intent is to shame, embarrass, and “punish” the individual by distributing their sexual images online. [↩]

- Snapchat is a mobile app that allows users to send photos or videos to select users for a brief time. The image or video disappears after 1-10 seconds. It October 2014 anywhere from 1000,000-200,000 photos were leaked after a third-party app (SnapSaved) was hacked. [↩]

- Pew (2014) reports that the overwhelming majority of Americans (81%) do not feel their data is secure on social media sties and 58% feel insecure sharing information via texts. [↩]

- Vickery, J.R. (in-press). “I don’t have anything to hide, but…”: The challenges and negotiations of social and mobile media privacy for non-dominant youth. Information, Communication, & Society 18(3). [↩]

- There are of course times in which people feel pressured to or are coerced into sharing intimate images. This is a violation of bodily integrity and sexual agency. However, in the context of this article, I am discussing the practice of consensually sharing intimate photos. [↩]

Pingback: Flow Column: Snapchat, Privacy, & Discourse | Social Convergence

I hate hate hate being sexted, and not having a penis.