Griefing, Grokking, and Meaningful Play in EVE Online

Morgan C. O’Brien / The University of Texas at Austin

In July, 2005, the CEO of a large corporation was murdered while relaxing on her private ship. An assassin had infiltrated the company for over a year, gradually working up the corporate ranks and becoming a trusted chief advisor to the now deceased CEO. The faux-employee enticed his target to a remote location in her luxury ship and executed her. Immediately afterwards, a secret society of mercenaries of which the hitman was a member – ‘The Guiding Hand Social Club’ (GHSC) – claimed responsibility for the crime. The assassination was committed for purely financial reasons – it was a cold-blooded murder, with no undertones of political or terrorist involvement.

In August, 2011, the two founders of investment company ‘Phaser Inc.’ ended what had been an elaborate Ponzi scheme, folded their company, and sauntered into anonymity to split over one trillion units of embezzled currency. For eight months, the fraudulent businessmen had fooled over 300 people a week to invest in their scheme by delivering a reliable 5% return on investments made.

Both crimes were widely reported across several international newspapers and websites. However, no litigious criminal or private actions were taken to locate and apprehend the perpetrators, nor were there any political recriminations made against the assassin’s parent group. There was in fact no forthcoming response, actual or anticipated, informal or judiciary, from any government, NGO, or law enforcement agency.

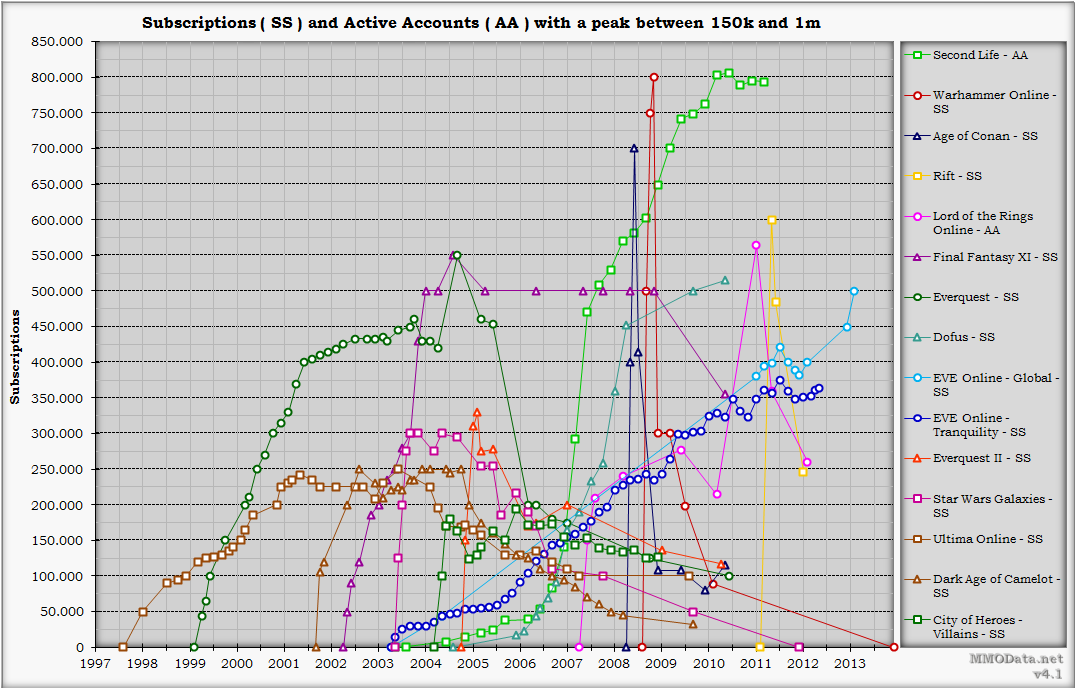

This is because these events occurred within the virtual world of EVE Online; a MMORPG or MMOG where both the assassin-player and the embezzlers’ actions are within the purview of EVE’s digitally signed end user licensing agreement.1 EVE is a globally popular game developed by Icelandic company, CCP, and currently boasts over 500,000 users regularly playing from around the world on one persistent server. While its number of active subscriptions fall short of the undisputed champion of MMOG’s Activision Blizzard’s World of Warcraft, EVE’s player population still rank it among the most popular of all MMOG’s.

In fact, while games like WoW have seen a steady drop in subscribers, EVE has managed to maintain a following that has consistently grown over the course of its’ 10+ years of existence. A remarkable feat considering that the game experience has not changed much in the face of increasing competition. Apparently, anonymously indulging in illicit behaviors never goes out of style, especially in the digital world where there is no fear of ‘real life’ repercussions.2

GHSC’s 2005 assassination and the 2011 Ponzi scheme are not the only EVE ‘criminal acts’ making headlines in mainstream news outlets. The Internet abounds with EVE anecdotes. Details of enormous PvP battles are aplenty, but so too are the intricate schemes that players indulge in, and also the RL financial relevance of EVE’s completely player-run economy – just as adversely affected by banking scams and warfare as RL. This division between the ‘real’ and the digital becomes especially tricky in games like EVE, where GW actions can have RL consequences. PvP battles and scams can quickly incur RL costs beyond the game’s monthly subscription fee, sometimes drastically so.

EVE’s social dynamics have been described as a “[…] controlled experiment in human nature and unfettered capitalism”.3 In EVE you can do anything to anyone and get away with it (or not), as long as you don’t expect others to treat you any differently. It is not a stretch to say that player existence in EVE is in accordance with 17th century political philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ ‘state of nature’, where life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”.4 Hobbes’ masterpiece of modern moral philosophy, Leviathan, imagines a world without central Government, where man strives solely for his own satisfaction in a society defined by the “war of all against all”, where only the strong survive.5

Looking past the sensational headlines surrounding EVE, observing how the game is being played can tell us something about RL society. Player engagement with game design in EVE’s environment raises questions about the concept of ‘meaningful play’ and the ‘reverse gamification’ of normalized socio-political ideologies (re: capitalism).

Gaming can feel ‘real’ because of meaningful play, something Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman call the “goal of successful game design”.6 Salen and Zimmerman differentiate between “descriptive” and “evaluative” game meaning – defining descriptive as the relationship between player action and system outcome, and evaluative as what takes place when these relationships are “discernable” and “integrated” into the larger game system.7 So, meaningful play arises in a game when, a) the player realizes certain actions will result in specific outcomes, and, b) player actions do result in anticipated outcomes from the game design.

Gamers learn as they play – the design of any game constrains and guides players while allowing them to pursue their own meaningful goals. EVE’s game design supports both the mundane and the nefarious, but also makes an argument for players gaining ‘meaning’ by behaving badly, not spending hours and RL money engaging in laborious tasks. However, can bad behavior really constitute truly meaningful play? At what point does meaningful play become unethical and what are the implications for RL? If meaningful play implies the designed purpose in a game system, then making it pleasurable to pursue deliberately unethical paths seems potentially troubling.

EVE is not a zero-sum game – there is no conclusive point of completion or even a way to ‘beat’ other players. Its persistent game world hosts a live economy – perpetually fluctuating according to player actions. Arguably, there is no easily comprehendible point of playing other than to acquire (in-game) capital and ‘grief’ other players.8 EVE offers players an optional quest-based system of advancement and opportunity to join player-created ‘corporations’ but many players opt to instead profit at the expense of other subscribers.9 When asked what separates his play style from simple griefing, the head of GHSC stated: “Absolutely nothing. We are griefers for hire. I can’t defend myself from this at all, since my corporation exists solely to provide the service of ruining other people’s good time until they break and scatter”.10

Game designer Ralph Koster argues griefing can be understood as a form of ‘grokking’ a game.11 That is, deeply understanding a game’s design and demonstrating the procedural and conceptual knowledge to manipulate it to further game experience beyond the recognized rule structure. Koster describes this concept pragmatically: “when a player cheats in a game, they are choosing a battlefield that is broader in context than the game itself”.12 Notably, EVE provides a grander scale for understanding how RL neoliberal activities are not necessarily beneficial in the long run – particularly resonant in today’s RL corporate global marketplace and mediascape.

While EVE features several different ‘career paths’ the main reason to play and the goal gameplay seems to perpetuate is simply to acquire as much as possible. Acquisitions include the in-game currency of InterStellarKredits (ISK), skills for your avatar pilot, different ships, blueprints for manufacturing items, ore from mining asteroids, etc. In such a way EVE embodies the tenets of a form of absolute capitalism – the game solely revolves around the accumulation of capital.

As EVE’s most basic play experience is predicated on capitalism, players must engage in labor to accumulate in-game wealth and abilities, potentially infinitely. Players can choose to either peacefully compete against each other for resources, or become robber-barons, bandits, and bankers – aggressively relieving workers of the fruits of their digital labor. Griefers can accordingly make EVE ‘meaningful’ by grokking that the game design allows beneficial outcomes as a result of actions that take advantage of other players. Perhaps a positive spin on this griefing style of play would be to understand it as a form of culture jamming – a way for players to subvert the designers’ prescribed play experience and engage in more individually ‘meaningful’ play.

Game designer and TED Talker, Jane McGonigal is optimistic about the effects playing games can have on society. McGonigal argues convincingly of the pro-social side to game playing, and suggests that RL activities should be made more like games.13 However, in a game without end, in which the only goals are to acquire capital at all costs, what can be said for what constitutes meaningful play and how it reflects upon gamers? What does this kind of meaning tell us about the larger society it takes place in? Play in EVE does not just occur within the fantastical vacuum of a game’s ‘magic circle’. Can the designed immorality of EVE’s online state of nature be justified as a way of creating meaningful play experiences? Since RL people have been robbed of RL money in EVE, at what point does meaningful GW ‘play’ become prosecutable RL crime?

Culture jamming itself becomes subverted in EVE, returning paradoxically to the pursuits of a neoliberal agenda. Ultimately, I’m unsure if meaningful play in EVE is an example of griefing, grokking, culture-jamming, or plain obeisance to neoliberal ideals. Most likely, play in the world of EVE is equal parts of each, just like the everyday tactics of RL. It is hard to imagine the pro-social benefits of a game like EVE and the behaviors it normalizes. On the other hand, perhaps CCP’s intent is to warn of the dangers of ‘unfettered capitalism’. If this is the case, they may have succeeded.

Image Credits:

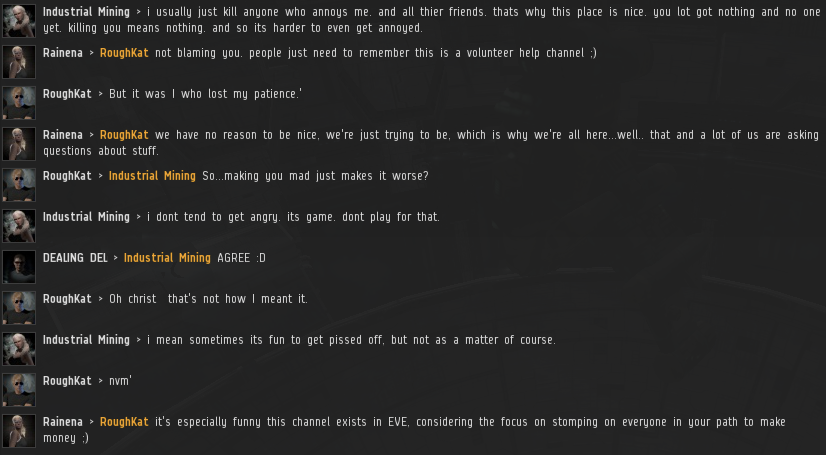

1. Griefing in EVE’s player help channel

2. Chart showing consistent growth in EVE subscriptions since 2003

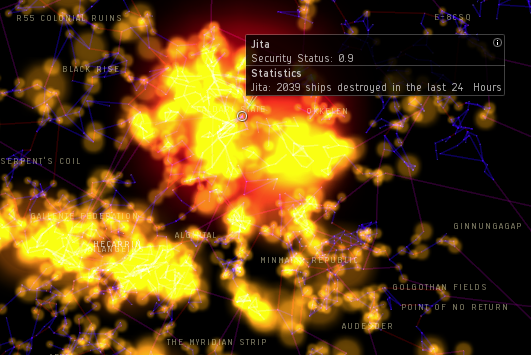

3. The war of all against all?

4. ‘kill’ heatmap showing player deaths across multiple solar systems

Please feel free to comment.

- Massively Multiplayer Online [Role Playing] Game [↩]

- I use ‘RL’ (Real Life) and ‘GW’ (Game World) throughout this article to distinguish between the two [↩]

- Vance, Ashlee. “Multiplayer game ‘EVE Online’ Cultivates a Most Devoted Following”. Business Week. Bloomberg., 18 Apr. 2013. Web. 22 Aug. 2014. [↩]

- Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Chapters XIII-XIV. Online Library of Liberty. 1909 ed. [1601] n.d. Web. 22 Aug. 2014. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Salen, Katie and Eric Zimmerman. “Chapter 3: Meaningful Play”. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004. Kindle file. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Griefing is the act of making other players’ play experience miserable [↩]

- EVE corporations fill the role that guilds usually play in other MMOGs. Framing a guild as a corporation highlights the capitalistic nature of EVE’s gameplay [↩]

- Ethic. “Interview: Istvaan Shogaatsu“. Kill Ten Rats. n.p. 12 Oct. 2005. Web. 22 Aug. 2014. [↩]

- Koster, Ralph. A Theory of Fun for Game Design. Scottsdale, AZ: Paraglyph Press, 2005. Print. p.112. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- McGonigal, Jane. Reality is Broken. New York: The Penguin Press, 2011. Kindle file. [↩]