They Should Have Sent a Poet: Faith, Grief, and the Female Mystic in Contact

Natalie Bograd / University of Texas at Austin

We embarked on our journey to the stars with a question first framed in the childhood of our species and in each generation asked anew with undiminished wonder: What are the stars? Exploration is in our nature. We began as wanderers, and we are wanderers still. We have lingered long enough on the shores of the cosmic ocean. We are ready at last to set sail for the stars. –Carl Sagan, Cosmos.

In one of the most memorable opening sequences in science-fiction film since its predecessor (and obvious inspiration) 2001: A Space Odyssey, the camera pulls slowly away from the Earth into deep space. On the soundtrack we hear the aural artifacts of humanity in reverse order from chart-topping music hits to the rich baritone of Martin Luther King and finally, silence. As we speed through the universe, interstellar clouds, nebulae, and zooming galaxies converge into a single point of blue light; a gleam in the iris of young Eleanor “Ellie” Arroway1 in Robert Zemeckis’s 1997 film Contact. Ellie (Jodie Foster) is a seeker. She goes from a precocious young girl attempting to reach truckers on her HAM radio to a SETI astronomer listening for—in her own words—“little green men.” Contact may be a film about one woman’s journey through space, but it is also about Ellie’s spiritual journey as she becomes a female Columbus in search of much more than a new world.

Notably, the sudden traumatic death of her beloved father as a young girl catalyzes not only Ellie’s atheism but also her deep-rooted desire to understand why things happen. The film’s most memorable sequence—Ellie’s eventual whirlwind journey through space—is both a quest for the answers to our biggest questions (what science-fiction humor writer Douglas Adams deemed “life, the universe, and everything”4) and a deeply personal spiritual experience. In a series of visually breathtaking scenes, Ellie travels through a series of wormholes. At one point, she arrives on the edge of a beautiful peach-tinged galaxy with a bright white-yellow sun in the center giving off unearthly rays of light. Ellie, narrating her experience for the record, is moved nearly beyond the point of the speech. Her voice trembling, Ellie whispers: “Some celestial event. No – no words. No words to describe it. Poetry! They should’ve sent a poet. So beautiful. So beautiful…I had no idea.” In a bit of cinematic genius, the face of young Ellie is superimposed onto Foster’s, the expression and voice flickering between that of the woman and child. The implication is that this journey is healing not only for Ellie but also for the little girl grieving the loss of a parent.

Ellie’s voyage becomes even more fantastical when she wakes up on an isolated beach with stars and galaxies hanging impossibly close in the sky overhead. A familiar figure soon joins her: her deceased father. No “little green man,” Ellie quickly realizes that he is actually an alien who has taken on her father’s form. The alien’s appearance as a dead loved one is part of the mystery of Ellie’s experience. Is this real, the ultimate wish fulfillment, or both? Regardless, the alien does what Ellie’s father Ted did for her as a little girl: tries to give her answers to her questions. Their brief conversation reveals that there are “many others” i.e, intelligent species beyond Earth, and that some of them have taken the same journey using the same cosmic transport system. In one of the signature lines from the film, the alien tells Ellie:

You’re an interesting species. An interesting mix. You’re capable of such beautiful dreams, and such horrible nightmares. You feel so lost, so cut off, so alone. Only you’re not. You see, in all our searching, the only thing we’ve found to make the emptiness more bearable…is each other.

Because she is a woman in a mostly male field and the scientific community considers her work for SETI fringe at best, Ellie is often alone and misunderstood. Because of the loss of her father, Ellie imposed isolation on herself, refusing to open up to people for fear of losing them. The alien’s prescription for humanity—that we realize how deeply connected we are to one another and the cosmos—is also a prescription for Ellie’s loneliness.

No longer the atheist defending her lack of belief in God, Ellie is now an evangelist attempting to convince others to believe. This reversal makes Ellie a prophet of sorts. It is significant that in Western tradition most explorers and nearly all prophets are men—Moses bringing God’s law to his people or Columbus discovering the so-called “New World.” In Contact, however, it is Ellie’s combination of scientific reason and female intuition that makes her such a powerful symbol. While Ellie is deeply shaken by the trial, she exits the courthouse to find a crowd of supporters cheering her name and holding signs that say, “Ellie discovered the new world.” Contact is such a significant film in the science fiction canon because it is a female hero’s journey. Ellie is not Uhura waiting by the phone while Kirk and Spock explore the foreign planet—she is the hero, following her destiny through a series of obstacles and returning home to deliver truth to us all.

Luckily, alongside soulless science-fiction blockbusters like Transformers and yes, Avatar—movies with great special effects but no heart—there have emerged a few gems. Films like District 9, Moon, and Her may be smaller in scale, but they share the same generic DNA as the best of their predecessors, making us think and entertaining us simultaneously. In addition, a handful of films and TV series such as Ron Moore’s Battlestar Galactica, The Hunger Games, and Orphan Black have delivered a new generation of female sci-fi heroes. As a female science fiction fan, I am often disappointed. So I hold out hope that there will be another Contact, a film that has stayed with me for over a decade and reminds me how powerful a storytelling tool film can be. I think about that little girl in her Darth Vader costume, lightsaber in hand, and am reminded that each of us has a quest of our own and the chance to seek out greater understanding. To boldly go.

To Coleen Hubbard and Larry Bograd, parents and longtime editors for encouraging all my obsessions from Star Wars to rock collecting to writing and for being the first to introduce me to this film. You are my guides through life, the universe, and everything.

Image Credits:

1.website Contact movie poster.

2. Opening images from Contact(Robert Zemeckis, 1997).

3. Author as Darth Vader (photo from author’s personal collection).

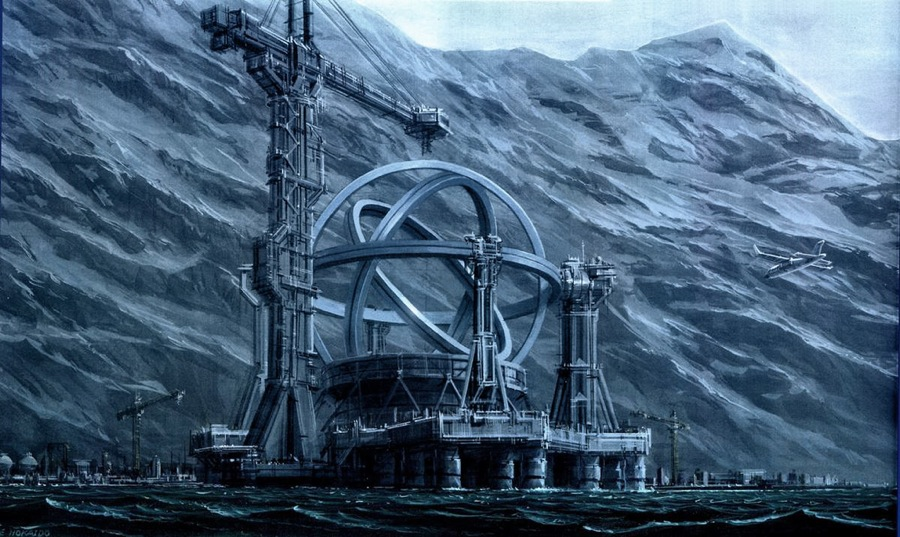

4. The machine built from plans sent by an unknown intelligence (Contact Robert Zemeckis, 1997).

5. Jenna Malone as Young Ellie (Contact Robert Zemeckis, 1997).

6. Ellie (Jodie Foster) listens for patterns in the chaos(Contact Robert Zemeckis, 1997).

7. Ellie has a mysterious encounter (Contact Robert Zemeckis, 1997).

Please feel free to comment.

- Young Ellie is played by Jenna Malone who went on to appear in multiple films including Saved! and the Hunger Games: Catching Fire and Mockingjay. [↩]

- This was later expanded on in the Star Wars Expanded Universe novels: Leia becomes a Jedi Knight in her own right but chooses politics instead, serving as Chief of State for the New Republic and giving birth to three children who all become Jedi Knights themselves. [↩]

- This is the name of the person chosen to test the machine, which is determined to be a spacecraft of some sort. Initially, the seat goes to Ellie’s rival David Drumlin, but he is killed when the first machine is destroyed in a terrorist bombing. Ellie discovers that a second machine has been built in secret and is then given the chance to go. [↩]

- This is part of a running joke in Adam’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series: the answer to “life, the universe, and everything,” (also the name of the third book in the series) is the number 42 but know one knows what the question is. [↩]

Nat,

You continue to be a soulful seeker. In addition to being an insightful appreciator/critic of the science fiction form, you are a graceful writer. Funny, I recently put “Contact” on my list of films to revisit. Deeper than people remember!

I loved you in your light saber years, I love you now.

Joanne

Natalie,

WOW!! What a great piece with so many interesting ideas expressed so well. I have not gravitated to science fiction and reading the piece gave me an expanded understanding of the genre. It truly is sci-fi, a mixture of science exploration ,which at it’s best teaches us about what it means to be human. I was also impressed by the importance in Contact of the hero being a woman. Contact is in this way is a trailblazing film which will help more and more women to high achievement in our real life sciences and in science fiction acting.

Your have a real gift for writing. Your writing is clear and flowing, and this made the piece very informative and pleasurable to read.

It is great that you chose to do your masters program in Austin . Congrats in having your piece in Flow. Reading this made me excited to be a part of all your future explorations in our universe,

Harvey

It’s interesting how the plot of these films are formed around such broad and universal questions yet they can help us inspire or find answers to our own more specific life inquiries. I really appreciated this viewpoint. As a female in her 20’s, I’m currently seeking answers to those “big questions” I rarely gravitate (no pun intended :) ) to science fiction films because I always assume they’re too abstract and fantastical to apply to my own life. This has been the push I’ve needed to give the genre a second chance!

Natalie,

A rich read precisely because it returns to a formative film in your youth, and is thus an example of identification at it’s best—a deeply personal and completely self-aware exploration of the relationship, as you put it, “between outer space and our inner selves.” That shot of you in your Darth Vader costume says it all! Like Art Spiegelman in his Cisco Kid outfit, you literally tried on at an early age what you wanted to become—and in this piece, you continue to try it on, the “it” being the process of wondering, wandering, exploring, intuiting, doubting, questioning, proving, and seeking. You’re the seeker here, the poet and female cine-mystic, too—as intuitive and intellectual as Ellie Arroway, as heroic in your quest for truth as that whole panoply of girls and women in all those other films, genres, and cultural contexts you know so well: Paikea in Whale Rider, Marjy in Persepolis, Hush Puppy in Beasts of the Southern Wild, Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster again) in The Silence of the Lambs, and, most recently, Waad Mohammed as the young female protagonist in Wadjda.

As you investigate the relationships between nature and culture, science and faith, technology and transcendence in and through the figure of Ellie in Contact, I am reminded of two things that seem to drive your intertwined journeys, one from Rebecca Solnit, the other from Caroline Walker Bynum. Solnit, citing Edgar Allan Poe in A Field Guide to Getting Lost, writes in that all experience and matters of philosophical discovery, “it is the unforeseen upon which we must calculate most largely.” Bynum, in her Presidential address on “Wonder,” ends with a lovely rumination that is a call to retain our capacity for an amazement “that yearns toward an understanding, a significance, that is always a little beyond both our theories and our fears.”

The unforeseen leads Ellie where she needs to go; your capacity for amazement infuses your writing.

Boldly going, you too shall find.

A beautiful, smart, expressive piece of writing.

Melinda

A wonderful, insightful, and warm piece of writing! As one who grew up writing to NASA for photos of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo astronauts — I can relate! Reminds me of the (unpublished) children’s book illustrated by Dirk Zimmer, in which the young protagonist escapes his family to lie on his back in the empty yard, wishing he could fall into the sky.

LB

As a lover of period pieces and not one with a natural predilection for sci-fi and fantasy, you bring up some fascinating points. In many ways, leaving the realm of what is or was allows a greater freedom to explore progressive ideas, particularly of the feminist variety. Sigh, I guess I should try to give sci-fi more of a chance. I do remember enjoying Contact after my dad forced me to sit through it. While I doubt I’ll start a willing journey into the literary side of things, you’ve convinced me to give the cinematic side another go.

It’s a very good essay, Natalie. In teaching screenwriting, and the foundation principles of screenwriting, the ‘what if…’ question is the central premise of movies–not just science fiction but essentially movie storytelling. Stanislavsky called the ‘the magic what if.’ We teach that it comes out what we call the ‘inciting incident’ or in mythological investigations the ‘call to adventure’. I’m sure you know all this so apologies if seems a bit obvious or patronizing. Such is key to structural development in screenplays. But far more importantly, the premise and its examination is central to the creative imagination and investigation of the writer. It is absolutely essential to the storyteller’s creativity. And what I often explore with screenwriters is just this–not simply the premise, but the ‘why’ of the premise. The why reverts exactly to what you explore in your essay: the why is an exploration of ego. Not the negative ‘ego driven processes’, but rather the exploration on oneself, on one’s journey of the world. Whatever genre we work in, and explore, as storytellers and artists, ultimately reverts to an exploration of ourselves–and not the broad, open questions or philosophical meanderings of the many, but the explicit, experiential exploration of each individual self–those ‘themes’ and ‘curses’ and ‘questions’ and indeed the anger that defines the individual. This is not just true to science fiction. It works in whatever genre one is writing in. When I lecture students all over the world now, it is always what I come back to: your story, your creativity, is in fact an examination of yourself, your place in the world. So your essay, Natalie, examines not only ‘Contact’ but far more importantly you– your reaction to it, your responses, your relationship vis a vis a work of art. That is a sure sign of a very good work of art. And it is a sign of a good writer exploring. Don’t stop doing so. And best…

Loved this essay, Natalie. I think the wonderful thing about science fiction, and you pointed this out so well in your piece, is how the questions these stories ask relate directly to our own inquiries about well..life, the universe, and everything. I feel that there is a duality between pondering about the universe and the world beyond ours, but also in how those ponderings figure into our own perceptions of who we are as individuals and how we fit into these roles. I love that you used Contact as your primary example. It obviously has great personal meaning to you, but I also remember relating to it in a very big way. I think the films of Zemeckis during the 90s and the early 2000s all have to deal with this send of who we are and where are we going. I mean, just think about the last scene in 2004’s Cast Away. Could you get any more existential? lol I think Ellie’s “spiritual” and physical journey into the cosmos is one of my favorite sequences in all of science fiction cinema. I do hope to see more females in science fiction, especially as the main protagonists. I completely agree with you about Princess Leia, btw. I think it’s important, especially for young children like you and me when Contact came out, to experience diversity and to slowly chip away at the unfortunate precedents set by Hollywood and the movie biz. Contact did a great job with that, and we can only hope to see that continue and expand in our new 21st Century mediascape.

First of all, Natalie, to see you again in the costume you wore as a second grader in my class, was a special treat. You were smart and thoughtful and groundbreaking then, as you still are. I still love the workings of your mind and to read your writing.

I don’t read much writing about film, and don’t watch much science fiction, and so I am doubly out of my element here. However, I watched and loved Contact when it came out. I think I have seen it once since then too.

What struck me as I made it to the end of your essay is that there is a sort of paradox here. Part of what made the film compelling was specifically the perspective and experience of a woman on this journey of exploration, a journey too often portrayed as more appropriate for men. And so in this way, the film was feministic. But the film also wants us to care about the message that is conveyed by the alien that “…in all our searching, the only thing we’ve found to make the emptiness more bearable…is each other.” In our culture of male privilege, this message might have gotten further coming from a man. Ellie says they “should have sent a poet” to capture the vision she encountered on her journey. In front of Congress she might have thought, “they should have sent a man,” not due to the limits of her capacity to communicate her experience, but due to the capacity of her audience to hear. As you write, “Ellie’s combination of scientific reason and female intuition… makes her… a powerful symbol,” but doesn’t it also make her a weaker messenger? Didn’t the film kind of empower and then pull the rug from under it’s heroine, and help her to look crazy? Isn’t that one of patriarchy’s favorite moves, the bait and switch elevation to a pedestal and then hurling to the ground of women?

(I am probably reaching here, though, and enjoying too much the opportunity to pretend that I am back in grad school myself.)

Keith,

You bring up an interesting point. I can see how the scene at the end may seem to diminish Ellie’s power as a character and messenger. I think there are two possible counterpoints to be made here.

1) After the scene where Ellie testifies, the President’s chief of staff (interestingly one of the only other women in the film and the only person of color) tells Kitz (the chief investigator) that Ellie’s recording unit recorded 18 hours of static, seemingly proving that her journey actually occurred. In this scene, the film comes down firmly on Ellie’s side. However, it is interesting that most of her journey is orchestrated by or influenced by powerful men: her father, her lover, and Mr. Hadden (the billionaire who guides her from a distance throughout the film) and that all the film’s antagonists are male including Kitz, the cult bomber who destroys the first machine, and her rival David Drumlin. I think you are right that the patriarchy is incredibly present in what is otherwise a very feminist film.

2) The second point is that perhaps it doesn’t matter if Ellie is/seems “crazy” or if people believe her. Throughout the film she spends most of her time trying to convince people that SETI is worthwhile and that her projects deserve funding. Ultimately, the journey is mostly important in confirming Ellie’s beliefs, allowing her to trust herself and become comfortable in her status as an outsider who has returned with special knowledge, as we often see in other heroic journey narratives.

Thank you (and all) for your kind words and provocative questions!

Natalie

This is fine for a subjective, hermetic review of a film from 17 years ago that had an above average critical reception and was slightly profitable at the box office.

I would expect something a little edgier or relevant from Flow but who am I to judge the academy?