Nowhere to Go but Up: Redeeming HBO’s Eastbound & Down

Nick Marx / University of Wisconsin – Madison

In June 2008 HBO took a minority stake in the comedy website FunnyorDie.com. As part of the pact, HBO ordered an original television series from the site’s main creative minds, Will Ferrell and director Adam McKay (Anchorman, Step Brothers). At the same time, the duo’s Gary Sanchez productions was preparing to release The Foot Fist Way, a low-budget comedy written, directed, and produced by North Carolina filmmakers Ben Best, Jody Hill, and Danny McBride. Even though Foot Fist performed modestly in limited release, Ferrell and McKay latched on to the trio’s comic sensibility and solicited them to produce the HBO comedy series Eastbound & Down (premiering February 15).

While I’ve only seen the pilot episode, I’d like to consider some already apparent issues; namely, that there’s a lot to not like about Eastbound. The series follows the bottoming-out of disgraced baseball pitcher Kenny Powers as he returns to his southern hometown and takes a job as a middle-school gym teacher. Kenny (played by McBride) is abrasive, spiteful, and unrelentingly egotistical. He drinks frequently and heavily. He cusses, especially at women and children. The other characters populating Kenny’s world-including his manipulable brother, his now-engaged former flame, and various starry-eyed fans-often serve more to absorb Kenny’s abuse than they do to put him in his place. By the end of the series’ pilot episode, we learn that Kenny grudgingly intends to stay at the school until he can work his way back to the major leagues. But if the program’s producers wish so strongly to portray their protagonist as a despicable person (a point driven home after a seemingly interminable sequence of Kenny snorting cocaine), how do they expect audiences to root for him week after week?

I don’t mean to suggest that we can’t be drawn to unlikable characters, especially comedians. Indeed, Kenny is part of a rich heritage of loathsome comedy protagonists, from Archie Bunker to Al Bundy. The most common strategy for creating audience rapport with such characters is to build their respective goal-driven actions into a story arc of maturation and/or comeuppance and to allow them to be seen as pitiable along the way. Eastbound, however, indicates that this is not the model it intends to follow. In one early scene, we see a close-up of Kenny lying on his bed after a rough day, crying. Just as we begin to feel for him, we cut to a wider shot showing the contents of his bedside table, including a stack of pornographic magazines. This quick betrayal of the audience’s sympathy is exacerbated in the following scene. Before his first day of school, Kenny pensively guzzles beer in his car while listening to his autobiography on tape. We’re treated to the following:

Undaunted, I knew the game was mine to win. Just like in life, all of my successes depend on me. I’m the man who has the ball. I’m the man who can throw it faster than fuck. So that is why I am better than everyone in the world. Kiss my ass and suck my dick, everyone.

Not only is Kenny’s profane soliloquy a refusal to allow the audience closer to him; it’s also an indication of how hard he is willing to push other characters in the Eastbound diegesis away. There is no maturation or comeuppance plot on the horizon for Kenny. If we’re going to follow Kenny’s crusade back to the big leagues, it will be on his terms.

Given its rejection of the traditional redemption narrative, Eastbound might be better viewed as another instance of so-called “cringe comedy” (offensive or embarrassing situations specifically designed to cause audience unease). Here, the pitiableness and maturation of the protagonist are secondary; the success of a cringe comedy series hinges on the degree to which its televisual asshole speaks to the asshole in all of us. Audience sympathy for cringe comedians, however slight it might be, is made possible by the highly personalized nature of their humor. The results can range from series structured around the idiosyncrasies of their protagonists’ comedic personas (as in the selfish misanthropy of Larry David) to ones serving as showcases for virtuosic performances (as in the chameleonic multitasking of Sascha Baron Cohen or Summer Heights High’s Chris Lilley). In the case of Eastbound, though, star Danny McBride (though he as a reputation as an adept improviser in the films of David Gordon Green) doesn’t have an established comedic persona on par with that of Larry David or Ricky Gervais. As a result, grappling with our repugnance for Kenny Powers at the strictly textual level yields a limited understanding of the series. I argue that we view Eastbound in a broader discursive context, as being integrated with its conditions of production and the cultural milieu it both constructs and comments on. Seen in this light, we can account for the stylistic elements of cringe comedy at play, as well as understand how those elements compel us to consider the larger implications of a character that acts purely in his own self-interest.

One character we might use as model for expanding our reading of Kenny Powers is South Park’s Eric Cartman. Cartman, like Kenny, drives the narrative of his show with racist diatribes and self-serving actions, often without retribution. In one recent example (“The Snuke”), Cartman’s misguided suspicions of a Muslim boy set off a chain of events that saves the town from annihilation. The episode’s uncomfortable life lesson is that sometimes, according to Cartman, “bigotry and racism [save] the day.” Such sentiments are clearly problematic, yet characters like Cartman and Kenny Powers go unpunished for having them. When considering offensive representations beyond their visceral, “cringe” impact at the textual level, though, we can see their integration into a variety of industrial and socio-cultural discourses. In the case of South Park, Cartman exposes the absurdity of extremism in American news media and political rhetoric; in the case of Eastbound, Kenny Powers embodies a collective American lassitude after nearly a decade of being told we were bigger, stronger, and faster than everyone else.

Kenny Powers is, appropriately enough, an offspring of the deluded narcissists Will Ferrell has long specialized in playing. And while FunnyorDie.com might too be seen as an exercise in Hollywood narcissism1 , its mix of professional and user-generated content has become a financially viable model that dozens of comedy sites are scrambling to emulate. Ferrell has maintained the site’s profile in part by using it as a cross-promotional tool for other projects, like last year’s touring sketch-show in support of his film Semi-Pro that also provided outtakes for the site.2 . On February 5 he began a live stage-show directed by McKay, “Will Ferrell: You’re Welcome America. A Final Night With George W. Bush” that will also be televised on HBO. Ferrell’s Bush impersonation falls right in line with the likes of Talladega Nights‘ Ricky Bobby-both are impetuous cowboys oblivious to those around them-so it’s plain to see how Ferrell and McKay were drawn to the same characteristics in McBride’s The Foot Fist Way.

It’s also tempting to draw parallels between Bush and Kenny Powers-both are disgraced national icons returning home, reluctant to own their blighted legacies-but here again Ferrell proves useful. His Bush impersonation reads as straight parody, an exaggeration borne out of the manufactured (and, by now, passé) red/blue divide. Conversely, McBride’s portrayal of Kenny, for all its surface crudeness, is more than a mere Hollywood response to the Blue Collar Comedy Tour. With Eastbound being shot in their native North Carolina (far from LA-based HBO executives) and using mostly local talent, McBride, Best, and Hill utilized their creative freedom to create a portrayal of the south that feels more lived-in than gleaned from collections of stereotypes.3 While I wouldn’t argue that the series posits any “authentic” notion of the south, it does create a comedic hero that embodies American cultural tensions of the recent past while warily embracing the changes to come.

Kenny, inspired by former Atlanta Braves pitcher John Rocker (who was also played by Ferrell on SNL), provides numerous reminders-literal (steroid use in baseball), metaphorical (Kenny’s shortsighted splurge on a jetski), and pop cultural (his stints in rehab)-of Americans’ selfish recklessness in the mid-2000s. But no moment better expresses it than a confrontation between he and his brother Dustin. As Kenny drunkenly pouts late one night, Dustin implores him to get used to living a modest lifestyle and to change his selfish behavior. Kenny seems to take this to heart, and the score swells as we see a moment of reflection flit across his face. Clearly, though, Kenny has heard what he wants to. “You’re sayin’ I gotta get back on top again,” he says, despite Dustin’s protests. “I gotta remember that I’m a winner, man. I need to remember that I am better than everyone else.” The exchange perfectly captures the selective hearing of pro athletes who thought they’d never be caught, political leaders sure we’d be greeted as liberators, and homeowners who never stopped to ask if it really was too good to be true. Sure, change is coming, and we’ll get back on top again. But for the time being, we’ll all, like Kenny, continue to wake up with a wicked hangover.

Image Credits:

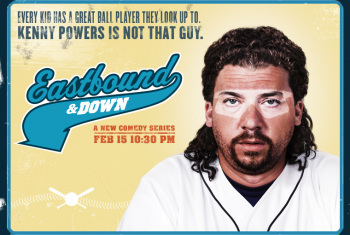

1. Eastbound & Down

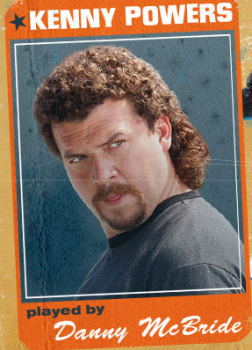

2. Danny McBride as Kenny Powers

3. Kenny Powers Promo

4. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

- See Heffernan, Virginia. “Mocking Stars and Beer Ads. Yawn.” The New York Times, 31 May 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/31/technology/31screen.html?_r=1. [↩]

- Curiously, especially for a series with Hollywood talent as recognizable as Ferrell attached, Eastbound has seen little promotion on HBO and broadcast outlets. Instead, the focus has thus far been online. When FunnyorDie.com premiered the second season of Flight of the Conchords weeks ahead of its run HBO, for example, and the episode ended with a promotional short for Eastbound. [↩]

- See the interviews with McBride and Best in Stephenson, Hunter. “Exclusive Set Visit! HBO’s East Bound and Down.” /film, 3 December 2008. http://www.slashfilm.com/2008/12/03/exclusive-set-visit-hbos-east-bound-and-down-with-danny-mcbride-david-gordon-green-and-ben-best-cameo-by-gina-gershon/ [↩]

Interesting piece, Nick. You are doing work I cannot do as a media scholar, primarily because I cannot stand Danny McBride. I don’t think he, his drawl, his gut, or his ironic mullets are funny. A large part of this has to be with being a feminist — while I know (or at least assume) a critique on white, hetero “proud to be an American” masculinity is being made, I find it hard to believe in because so often characters like Kenny Powers (or Eric Cartman or Homer Simpson or David Brent or Michael Scott or Archie Bunker or . . . or . . .) are made into some kind of hero or underdog or even cast as sympathetic (for example, I can’t think of an episode of the American “Office” where Michael doesn’t go completely over the line — outing a gay subordinate, sexually harrassing a female admin assistant, humiliating an alcoholic single mother, mocking employees of non-white racial and ethnic groups — and then squeeze out a tear after he gets called to the mat, making us, the audience, remember what a lonely, insecure guy this unlikeable boob is and want to put our arms around him.

It doesn’t sound like anyone wants to put their arms around Kenny Powers, but as you argue it to be a part of a larger sub-genre called “cringe comedy,” I wonder if there is any substantial critique of whiteness, masculinity, heterosexuality, or Protestant religious values actually goes on or if cringe comedy in fact reaffirms the hegemonic power of these identities. I’m overwhelmed by how unbeliveably white, male, straight, and Protestant the examples you provide are (Larry David aside, who is Jewish). Does the “cringe” in cringe comedy come from how regressive these men are when confronted with identity differences or more progressive ideologies? Does their racism, sexism, and homophobia — along with their bodies, as many of these examples are doughy boys and men — make them “failed” men? Or do their failings make them somehow heroic? Do these shows actually take identity politics to task or do they ultimately reinforce that staid gender norms, sexual politics, Protestant religious practices, and racist ideologies are correct? I can’t help but think about how unchecked these characters behavior and actions often are when other cringe comics like Sarah Silverman (a Jewish female comedienne) are often taken to task for controversial aspects of their work. I also can’t help but read this genre alongside Dave Chappelle’s feelings of discomfort when white men started laughing for the “wrong” reasons at racially-charged sketches on “Chappelle Show,” cancelling a tremendously popular and lucrative television franchise as a result.

In short, I’m asking that if people find this kind of humor funny, why are they REALLY laughing? Are they laughing with these characters, or at them?

Alyx, I think it’s the inability to easily answer your final question that has often stopped a lot of comedy research before it begins, since we can’t ever know, and surely there’s variability in why people laugh. While personally I don’t see the payoff over an entire series, I can see, for instance, how one might laugh at Kenny in the same way that one might laugh at Lil’ Bush — angrily and censuriously (which doesn’t seem to be a word, but hey, let’s make it one for now, shall we?). Ultimately, though, I think we need a performance studies approach to get at this, since a lot of comedy is about an interaction between audience and what’s on the screen (a reason I think it’s a pity that there isn’t more comedy research, since all images work this way, but it seems as though comedy makes the interchange more explicitly obvious. If we could unlock some of the secrets of what audiences bring to comedy, especially apparent oddities like cringe comedy, we might have a better sense of what they bring to other genres too), one that makes it impossible to get the comedy by studying the text alone. I think that was Chappelle’s failing — in thinking that he ever could control the text. He left his show, as you note, because he worried that white viewers weren’t reading it the way he wanted them to, and he missed the control that (he thought) a standup has over such situations. But even with standups, the comedy will always be produced in a performative interchange. It’s a slippery beast, which, as I noted at the outset, is probably behind the small amount of comedy research (especially odd for a genre that basically ruled supreme over the Nielsens until the 90s), and so I think it scares people away, or can be examined as if the audience doesn’t exist. Yet, to reword the above, understanding cringe comedy may be our best way to understand audiences in general.

All that said, while Nick makes me interested in studying or analyzing Kenny, and while some might laugh at/with him, he doesn’t give me much hope that I’d actually enjoy watching it. As he notes, one of the interesting things with Kenny is how thoroughly unlikeable he is. That might just be the pilot, and perhaps he’ll get some niceness drilled into him at some point. But in contrast to some of the other figures that Nick and Alyx mention — Homer, Al Bundy, Michael in the The Office — he just sounds boring. Indeed, that would be my “defense” of Michael to Alyx’s concerns: that he’s a more interesting and realistic depiction of racism, homophobia, etc. by having a nice edge too. We do ourselves a disservice if we depict all intolerance as Hitler- & the Spanish Inquisition-like, and while it may be comforting to make a racist character, for instance, a horrible James Bond villain, and while that may try to close down the possibility of misinterpretation, it’s too polarized and unrealistic, and I’d rather ponder characters’ intolerance when it comes in spite of some other positive attributes than in stark evil. Kenny just sounds boring. So where I see significant potential (even if not realized, or if poorly rendered in some instances) for thinking through identity politics with some of the other characters mentioned, I’d agree with Alyx that Kenny sounds fairly barren, at least on the surface.

Great piece, Nick. Having just watched the pilot episode this seems like a very logical extension of the McBride character that has been seen now across various films — with an exaggeration of a few of the elements. I think Alyx points to the key identifying characteristic of both Kenny and the show: failure. That’s not a new trope in media about masculinity, but what’s on full display in the show is the way Kenny embraces his failure and ignores what seem like “logical” ways out. The show seems to be pushing the boundaries of what’s been happening for a while now (especially on television, some examples of which Jonathan points out), but does so with a relentless glee that makes no apologies. This isn’t just appropriating juvenile behavior as part of adult masculinity (which Tim Havens wrote about for Flow some time ago — see: http://flowtv.org/?p=857), it’s rewriting “successful” adult masculinity as that which has failed. I’m not sure I’d put this in the same category as other “cringe comedies.”

It might be part of the trend started by Adam Sandler, continued by Vince Vaughn (and, as Nick points out, Will Ferrell), and then seized by Seth Rogan and Judd Apatow –who, in turn, have worked with McBride. The films made by these men certainly induce cringing, but not the same way as someone like Sarah Silverman or Dave Chappelle. I don’t think there’s much of a critique of masculinity happening in the show — rather, like Apatow and Rogan’s recent work, it’s more of an effort to rewrite what it means to be a “man” in a culture increasingly attuned to criticisms of masculinity. What better way to rescue John Rocker and his ilk than to create a sitcom out of it? The comedy creates the perfect alibi, in a sense “forgiving” the behavior by making it seem outrageous (and thus “safe”) while all the while aligning the viewer (narratively, aesthetically, and through the construction of the humor) with the slow reclamation of “success” for Kenny.

When this first came across the Flow editorial “desk” I knew I recognized McBride — and not just from the recent slew of Farrell/Apatow-ish films. My trusty friend imdb reminded me that McBride’s first role was in *All the Real Girls* — a heart-rendering and quiet film written adn directed by David Gordon Green before he was “promoted” to helm Pineapple Express. I remember a bit of discourse around Green’s attempt to bring his indie sensibility to the Apatow comedy (do these mesh?) but I’m most interested in the evolution of the McBride character. In *All the Real Girls,* he places, in some ways, the selfsame character described above and in evidence in the preceding string of films. While he provides a sort of comic relief, he also the sweetest, most tender center of the film. A baffoon (he referred to exclusively as “Butt-ass”) with an innocent, compassionate soul, which seems quite different from these other characters. This also seems to be the sort of alternate masculinity that Peter is positing — a Seth Rogen of sorts — dumb but sweet, overweight but soft, devoted to drunkenness and brotherhood but secretly in need of the love of a good woman?

I’m also thinking of star texts — it’s obviously that Rogen and Ferrell play “themselves” in film after film after Funny or Die skit after cameo after awards show appearance. Can a comedian NOT play himself? Will McBride always be the dude with a quasi-mullet and southern accent and vacant look in his eyes?

I thought that I’d join what has turned into a fairly lively debate. My question relates to the new-ness of the Danny McBride characte/template, and I guess when looking for precursors, I wonder why we haven’t mentioned The Bad News Bears “phenomenon” (film 1976, sequels in 77 and 78 and the TV series in 79, remake in 2005). I only suggest thisbecause it seems to present a similar object for comparison, particularly as the curmudgeonly (and often drunk) Coach Buttermaker (Walter Matthau, Jack Warner, and Billy Bob Thornton repsectively) working with children, seems to be the taboo here that charges the little league games with their comedy, rather than the Bears triumphant successes in the Astrodome or in Japan.

Placing McBride’s Kenny in a genealogy of despicable comedic protagonists, Nick’s early reading of this character certainly makes it seem that Eastbound is testing a sort of limit with “cringe” comedy. As Jonathan rightly points out, what makes a lot of these other self-absorbed, homophobic, racist, and/or sexist characters defensible (and watchable) is what they might be doing to nuance our understandings of their biased perspectives, but this only seems possible if there are redeeming or vulnerable traits available to cast their transgressions in some relief. Conversely, Kenny appears to be a pure emblem of much that is wrong with American white heterosexual machismo, and if that doesn’t subside over subsequent episodes, I have to think that any potential audience could have trouble relating over the course of a series.

However, I’m not very concerned about Kenny reaffirming his type. While I see Alyx’s point, I have much less of a bone to pick with a character that seems so clearly to be satirizing its object. It may be that Kenny will offer little insight into his bad behaviors, but there’s also little likelihood that the Blue Collar Comedy audience will be celebrating him as the next Larry the Cable Guy either. Ceding that cringe comedy may not always be as sharp as one might wish, I’m much less troubled by its political ramifications than the vision of white American masculinity offered in less stark terms across many of the remaining old school sitcoms (Two and a Half Men, According to Jim, etc.) and a different HBO comedy series – Entourage. Nick hints at the end of his piece that Kenny, though thoroughly unlikeable in his own right, may be the retrograde center that allows the series to paint a subtler picture of the contemporary American South around him. As for Vinnie Chase and his boys, there is really no hope for them to show Hollywood in any similar light. Despite their having many of the same nefarious character traits as other cringe protagonists, these are hardly ever responsible for any of their misfortunes. Sure, Johnny Drama may be slapped occasionally for his particularly ignorant moments, but largely, these guys escape any real sanctions on their behavior. In fact, they typically benefit from it. The comedy in the series is rarely directed at the characters as it is usually aimed at the machinations of Hollywood and the entertainment industry writ large. Vinnie’s Entourage is celebrated by the narrative as rightful heirs to the throne of celebrity bad boydom, allowed to float by in a suspended state of immature hubris. The very fact that the troublesome nature of Kenny is already at the center of our discussion of the show makes me much more hopeful for Eastbound‘s critical/comedic potential than I am about a lot of other less aggressively provocative television comedy.

All: thanks for the great feedback.

Alyx, you raise a really important issue. I shied away from directly addressing it partly due to length concerns, but mainly because I believe studying comedy in terms of whether or not it reinforces or subverts a particular set of ideologies can be limiting. As Jonathan notes, the relationship between comedian and audience is slippery, and in many cases it becomes difficult to determine if audiences are reading a particular text/performance in the way the comedian intends/hopes for/explicitly puts forth. In arguing for Eastbound as being integrated with a broad network of discourses, I hope we can begin to flesh out in more nuanced ways the myriad manners in which audiences engage a seemingly straightforward comedic text. With that said, I won’t pretend that Kenny’s brazen misogyny, racism, and homophobia are not problematic, and I agree that even when these characteristics are tempered with pitiability (as in the case of Michael Scott et al.) they represent a rather feeble critique. But this is what drew me to the show as an object of analysis and a point on which I disagree with Jonathan. I’ve become bored with television comedy protagonists that have “a nice edge too.” To be sure, plenty of great scholarly work exists on how the Homer Simpsons of television, through the mechanisms of intertextuality and parody, enact various social and cultural critiques. But what about the characters we so often dismiss as irredeemably offensive and monolithic?

This is where I find the Eric Cartman example instructive; yes, he’s an unrepentant anti-Semite, and there is real danger in broadcasting these sentiments to the world in a comedic context. But if we recompose ourselves after the initial cringe and consider Cartman’s hate-speech among discourses of South Park’s production (weekly, enabling it to comment on contemporaneous events like Gibson’s post-“Passion” media-circus), and exhibition (on Comedy Central, aligning it with the like-minded media critiques of TDS and Colbert), we see how Cartman can be read as mocking not only religiously-extremist ideologies, but also the way such ideologies are discussed and mediated. This is part of what I think Eastbound is up to–commentating on (and mocking) our impulse to define the male American hero as this or that.

yeah, Cartman is a notable exception to my preference for characters with some likeability. I wonder, though, if this is because the show renders him one of a group. It’s a problem in analyzing characters, after all, that some are individual, some are parts of a clump (much as, for instance, a Spice Girl or a New Kid on the Block is one fraction of the uber-being), and some are largely foils or reflections (as with many of the characters in Dexter in S1 at least). Hence the significant change in dynamics from Seinfeld to Curb, when George effectively becomes the centerpiece, not just 1 of 4. I wouldn’t want to see a show about just Cartman, and while you may be bored by the “nice edge too” characters, Nick, I’d pose that Stan and Kyle form that “nice edge too” for the larger “character” that is the boys. Or have I tried to force you to agree with me by dragging you in a dodgy back door? ;-)

Round 2:

Peter–your thoughts re: failure and rewriting masculinity are spot on. Thanks.

Annie–I agree, there’s an extent to which the DGG/Apatow/Ferrell boys club (and many other comedians) are rehasing their same schtick across platforms. But, as with the Seidman “comedian comedy” model of star texts, this tends to slot the comedian’s performance into a framework privileging genre over historical and industrial context. For example, from what I’ve seen in promos for the show, Ferrell has a bit part as (surprise!) an eccentric car salesman. I’m inclined to think that this is less “Ferrell-being-Ferrell” (though it certainly is that), and more Will Ferrell-the-executive-producer lending the Hill/Best/McBride troika his clout to get a somewhat risky show made. I’d be interested to hear more about how you think he (or McBride’s star-text) functions in the series, though, as it progresses.

Colin–right, I don’t think Kenny represents anything new per se, but he is an interesting variation on the more pitiable cringe comedians we’ve become accustomed to. Bad News is a great idea for a precedent (thanks), but I’m not sure Coach Buttermaker holds a candle to some of the dialogue and actions we see from Kenny in just the first episode alone.

Dave–thanks for bringing up Entourage, a show I find just as loathsome as many of us debating here will likely find Eastbound! Your point about “less aggressively provocative” comedy is well taken.

Jonathan: Ha, Cartman does indeed tend to function more often as part of the group character; though the particular examples of offensive ranting I’m thinking of (“Passion of the Jew,” “Cartoon Wars”) are ones in which he flies off the handle and makes a point of separating from the others.