Soundalikes and Disrupted Pleasures

In “Intellectual Property,” season one, episode four of Aaron Sorkin’s Sports Night, Dan Rydell sings “Happy Birthday” to his on-air partner Casey McCall at the end of one of their sports broadcasts. Rydell is surprised that an executive from the accounting department calls him to task for singing “Happy Birthday” without having it approved through proper channels, given that the accounting department must now juggle the production budget to pay for the licensing and public performance rights of the time-honored birthday serenade.1 Rydell’s consternation mirrors the consternation of listeners and fans unaware of the legal and economic backstories of production and distribution of the music they hear in their everyday lives. As the amount and variety of music in television, gaming, and various forms of new media increased during the 1990s, complex negotiations involving licensing, copyright, contracts, and intellectual property law shrouded the backstories of media production in economic and legal language. DVD releases of series such as Freaks and Geeks and La Femme Nikita were delayed for years, and producers often paid through the nose for the use of classic rock songs, oldies, and established artists. Other releases such as the DVDs for The Chappelle Show simply left out most of the musical numbers and performances, since producers either could not negotiate decent rates or felt that paying licensing fees wasn’t worth the trouble.

One of the most noticeable ways that these backstories have become visible is in the discussion and derision of soundalikes in the DVD releases of television series and in video game content. Soundalikes – the act of replacing an artist’s song with something that sounds vaguely similar – result from licensing and revenue sharing issues that arise when a television series transitions from broadcast to DVD home distribution or from a game publisher’s desire to cut production costs. In order to expedite DVD releasing and manage game development or television distribution budgets, producers began using soundalikes in order to avoid expensive licensing fees. Soundalikes are songs that to the casual listener sound similar to the songs being replaced, but these songs are often written and/or performed by new and emerging artists that do not carry the high price tag of A-list singers and songwriters. While the use of soundalikes made economic sense, the practice angered fans and threatened to cause a backlash from angry performers whose work had been replaced.

The WB and production companies working with the netlet angered fans when programs such as early seasons of Felicity and Dawson’s Creek were significantly altered in the transition from broadcast to DVD, with original songs replaced with soundalikes. The choice to use soundalikes annoyed viewers who wanted to watch the broadcast versions of shows they had followed over multiple television seasons. The move also affected those who experienced and decoded the narrative based on the specific songs and stars whose music was incorporated into television programs. For instance, teen girl fans of the music of Alanis Morissette or Tori Amos might combine their readings of the music, Morissette/Amos’ star text, and the visual and dialogic elements of the television narrative. Replacing Morissette or Amos with a musical unknown would significantly alter the sources of viewer pleasure and identification.

Similarly, gamers playing Rock Band or Guitar Hero quickly noticed the difference between the use of actual master recordings and the use of soundalikes for tracks that were “made famous by” the original artists. Classic rock fans and Generation Xers were not amused.

And the use of new songs or new renditions of the title credits on The Cosby Show and later seasons of Married with Children have made these shows unwatchable for many audiences and less useful as pedagogical tools in media studies classrooms.

The use of soundalikes also had the potential to provoke litigation from A-list and iconic artists whose work had been replaced with musical unknowns. Lawsuits lodged by Bette Midler against Ford Motor Company and by Tom Waits against Frito-Lay created precedents for the protection of vocal style under the right of publicity theory and extended this right to soundalikes.2 In these two cases, corporations wanted to use Waits’ and Midler’s work, the artists refused, and the companies used singers to mimic their vocal style. While these two cases posited that the artist’s image had been harmed and that the corporations had intended to fool the public into thinking that it was really Waits and Midler singing, they did alert media producers to the potential dangers in using soundalikes to stand in for iconic recording artists.

This made the soundalike strategy a legally defensible position only with the use of musical unknowns whose image, star text, and memory were not kept under constant scrutiny; in these cases, however, producers could probably afford the original in the first place. For example, replacing iconic artists on The Wonder Years soundtrack with soundalikes in order to release the show on DVD (which has not yet occurred and may never occur) might threaten to spark litigation regarding the rights of performers and copyright holders. If producers intentionally used something sounding like Diana Ross and the Supremes or Elvis, lawsuits arguing that producers intentionally chose soundalikes in order to subvert contract law and industrial policies governing licensing rates might be filed against program producers and distributors.

Soundalikes also raise methodological problems regarding how we do textual analysis by making the formal analysis of television and game texts historically contingent. Television’s early encounters with the music industry were highly charged. Since I had not archived the original airings of many of the series I consider, I have had to rely on DVD releases and friends’ collections of over-the-air broadcasts, and thus my analyses of television texts may run counter to the memories of some audiences who accessed these texts in their broadcast run. Convergent strategies in the culture industries have made textuality historically contingent at the same time that these strategies potentially multiply the channels of discourse, making it important that we specify our objects of analysis and the distribution method in which texts were accessed. Soundalikes re-establish the need for us to archive over-the-air broadcasts and the first runs of programs, as these programs are often significantly different from syndicated and DVD versions of the same titles. Soundalikes may also tell us a great deal about how the texts we see on American screens are modified for British, Australian, and other foreign markets.

For media historians for whom primary research materials may be limited to commercially available products, the choice is to analyze the materials that have been successfully licensed and made commercially available to the public or, in attempts to specify original textual materials, to rely on information compiled by fans, which is often incomplete and of questionable veracity. It follows then that shows with a devoted fan base will have more visible traces on the web and in fanzines and that in these cases fan sources will become more prominently featured as sources of evidence. In short, soundalikes alert us to how malleable televisual sound truly is and render claims regarding the meaning and reception of televisual mobilizations of popular music more difficult to make.

Image Credits:

1. Sports Night

2. Guitar Hero Closeup

3. Married with Children

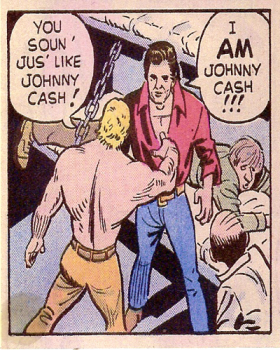

4. Johnny Cash Comic

Please feel free to comment.

What’s most thoughtful about this piece is the underlying importance of diegetic and non-diegetic music and soundtracks in our pleasure and readings of media. So much notable attention has been placed on preserving images but I feel less so on preserving sound and soundtracks, which can sometimes be more expressive of onscreen emotion and thematic happenings than the imagery. And in the case of Rock Band and Guitar Hero, the music is the centerpiece with cover bands standing out (sometimes painfully) among the master recordings of famous music groups.

As you illustrated, this is a struggle between business practice and artistry with audience and fan considerations tossed into the mix.I am very curious about how these soundalikes and replaced music alter one’s reading of a text. How do viewers of original broadcast TV shows deal with the changed DVDs in their relationship with the episodes? There is the original memory of viewing the episode that undoubtedly comes into conflict with these substituted ones. I experienced such changes watching the first season DVD of Roswell, specifically the first episode’s opening scene. Formerly opening with Eagle Eye Cherry’s “Save Tonight,” I was thrown off by the switch on the DVD release. Actually, I wasn’t sure if I had imagined the Eagle Eye Cherry song on the episode, so I dug out my VHS taped-from-TV premiere episode of Roswell and confirmed that the switch was made.

It bothered me as a fan, but even moreso as a media scholar for the reasons you pointed out. That history, the intended audiovisual relationship, is completely lost to those without access to the original broadcasts or memories of viewing. However, it seems we find ourselves in a Catch-22: copyright issues have prevented viewer access to many popular classic TV shows not in syndication but shows released on DVD often have substituted music, fiscally overriding copyright issues yet changing the original text. While arguably scholars have greater access to archived media material, I can only think so much has slipped through the cracks. Furthermore, that access is not extended to the greater public.

How do we reconcile this convergence issue? It is a question that has sparked in my mind for further thought.

It seems as though we’ve come full circle, as in the eighties it was almost impossible to license popular songs for B-grade movies. I also wonder what will happen (or has happened) to songs that were directly promoted by particular shows such as Gray’s Anatomy and The O.C. Overall, this article definitely raises some great ideas and ultimately asks the all-important question as to when and where we will ever get to see the Wonder Years again.

Rick Linkletter once observed that licensing Aerosmith’s “Sweet Emotion” for his film Dazed and Confused cost more than the

entire budget for Slacker. And I agree this causes major problems for historians of broadcasting, not only in terms of the substitutions, but in terms of certain programs remaining completely unavailable. Get A Life, arguably one of the most influential series for contemporary “edge” comedy, remains unavailable in any form almost twenty years after its debut precisely because of this issue.

As I’m sure Ben is aware, this was also a prominent strategy among the budget-line record labels of the ’60s and ’70s. Several labels specialized in anthologizing recent pop hits “performed in the style of…” At the point, the idea was that children and young teens were not very discriminating consumers or listeners–that a cover of The Archies “Sugar Sugar” was qualitatively not much different than the “real” recording, and if it was half the price, so much the better. Of course, that seems unthinkable today, suggesting how much better trained audiences are in hearing texture, production, “authenticity,” etc…

I find it particularly unfortunate that those who represent music artists and television producers cannot come to some sort of middle ground. DVD has lifted TV out its ephermal state in ways that not even cable channels such TV Land can do. But these soundalike soundtracks are bastardizing the original work of both the music and the television programs. I’ve also heard that it is domestic distribution agreements that are the hardest to settle. For instance, Ally McBeal (which features work by artists like Barry White) has been released on DVD in various european countries but there are not plans for a US release.

Pingback: warsystems » Sports Night season 1 episode 4 clip 2

Thanks for raising so many interesting issues. Colin, in answer to your question, producers and music supervisors on series such as The O.C. have worked hard to ensure that the purchased rights extend to home distribution, even though there remain series such as Cold Case that seem to be stranded on broadcast television. MB, you bring up an excellent issue regarding the ways that national and regional markets determine the value of artists’ work and the prices that copyright holders and publishers can charge for particular artists. Might it be that Barry White’s music and star persona have less economic value in Europe, meaning that licensing White’s music in Ally McBeal is less expensive for the distributor and the production company than it would be in the US? This seems to be the case with House, where Massive Attack’s “Teardrop” is featured in the US title credits, while the theme music from the show’s closing adorns the opening to the UK version. While Massive Attack remained a niche favorite in the US in the 1990s (what college radio station didn’t play Mezzanine?), trip-hop artists popularized a Bristol sound in the UK, making them more expensive to license for British distribution. Racquel, you hit on the issue of memory and the fact that we can no longer ignore the fact that textuality is historically contingent and much more malleable than many of us would prefer.

Pingback: TV theme songs: Joan Jett and the Blackhearts and Freaks and Geeks « Feminist Music Geek