Wise Men from Fools

Kristopher Mecholsky / Louisiana State University

“The whole town knew about the cloth’s peculiar power, and all were impatient to find out how stupid their neighbors were.”

—Hans Christian Andersen

This article is the last of three articles I’ve written here on representations of meritocracy in American television. By meritocracy, I mean it roughly as Michael Young coined it in his satirical novel The Rise of the Meritocracy: a system in which each participant gets what he or she deserves, each rewarded in direct proportion to individual effort and ability. The first two articles sketched out some of the ways in which I saw the ideals of a meritocracy depicted on various television series, focusing particularly on NBC’s The Blacklist and the potential I saw in it as a challenge to the popular replication of the meritocratic ideal that many shows engendered.

But The Blacklist threatens to be just one more in a list of network and cable dramas (as I suggested previously) that seem to glorify the antiheroes, “great men” (and they are usually men), and meritocratic ideals that I think those shows are usually slyly critiquing. If these shows are meant to poke holes in America’s belief in its meritocracy, they’re doing a terrible job because people are throwing Draper parties left and right, uncritically co-opting (admittedly) cool style with all its ideological baggage but none of the feminist critique a show like Mad Men actually provides.1

In this “Golden Age of Television,” the networks are often left behind in ratings and critical estimation. Yet, if we’re criticizing a lack of diversity in what is popularly considered quality television—as Willa Paskin did passionately at Slate, noting that shows like Top of the Lake and The Fall have not received the “frenzied attention” of shows like True Detective2—we might want to turn our attention back to the networks, at least for suggestions for a way forward. For the past 10–15 years, a number of American network comedies have been trying to dismantle our illusions about meritocracy.

While we tell ourselves daily that we deserve our jobs and wealth—and while we habitually watch shows about detectives, lawyers, doctors, and even real-life performers who glide their way to the tops of their fields—some shows on NBC, ABC, Fox, FX, and even CBS have been skewering the idea that America is a homogenous, meritocratic system that doles out rewards in direct proportion to effort and ability. Shows like Arrested Development, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, The Office, 30 Rock, Parks and Recreation, and Brooklyn Nine-Nine have instead been revealing a hilarious universe frequently populated with self-involved, lazy, inept, undeserving drones.

Not that we dislike them. At their warmest, as in The Office, Parks and Recreation, and Brooklyn Nine-Nine, these shows nevertheless celebrate the general populace who carry out the day-to-day tasks necessary for a society to revolve. But none of these shows have taken on the particular problem of the myth of meritocracy as directly as The Office. And in no season was it more consistently the center of the show than in Season 8, when James Spader starred as the new CEO of Sabre: Robert California.

At its start, The Office moved among a few (primarily romantic) narrative arcs, but from about Season 3 on, the business politics of Dunder Mifflin, the Michael Scott Paper Company, and Sabre become a driving force behind most of the season’s arcs. The show takes a central interest in how its characters influence and are influenced by the company they work for. How the managers and CEOs treat the lower employees are of particular concern. While romantic tensions still drive many of the particular episodes and help define some of the season arcs (particularly Dwight and Andy’s romantic lives), the characters lives’ begin to revolve more decidedly around the business they practice daily, in particular through their interactions with upper management. In other words, the episodes began to interrogate their relationship with those higher up in the “meritocracy.”

Had I world enough and time here, I would also talk about how the show used Michael Scott and Ryan to dissect the American business world because the show began its most thoughtful critiques in Season 2. Yet while the entire series becomes increasingly cynical and critical about upper management practices, it does so in a way that tries to celebrate the low-level workers at the center of the show—and of every business. This is why I point to Season 8 as the culmination of the series’ efforts to dismantle our knee-jerk praise of management over daily paper pushing (literally!). Moreover, I think it’s notable that Paul Lieberstein (who also played Toby) was the series show-runner for seasons 5 through 8, when the season arcs began to concentrate more devotedly to the struggle between workers and management. I think it is no coincidence that an early defining moment of the show’s heart occurs in the second Lieberstein-scripted episode (2.7), “The Client,” when Michael wins over Lackawanna County representative Christian because he demonstrates that he cares more about people than profit (he would rather talk to Jan about her divorce, order appetizers, and make jokes than move right into business) and because he’s lived in the county his whole life and cares about it.

When Robert California arrives to Scranton, at first to replace Michael and his original replacement (played by Will Ferrell), he enthralls everyone. His aphorisms are so richly euphonic that the office presumes he must be a genius. Over time, however, it becomes clear he is actually a hedonistic egomaniac who might destroy the company. The moment that epitomizes the transformation of the Scranton office’s view of Robert California is his entrance after the credits in Season 8, Episode 23. A hungover California enters the office, shushing everyone. He looks around, and then lunges for the garbage can next to Jim’s desk, puking audibly. In celebration of the finalization of his divorce, he explains he had “a one-man Saturnalia last night.” It is soon revealed that the Binghamton branch has closed, and the Scranton sales team is trying to land their clients. California reveals in a confessional that “closing the Binghamton branch never occurred to me before today. Or…I guess, last night. But! In vino veritas, as they say. I’m not going to start doubting my drunken self now.” Robert California’s integrity is so strong that he implicitly believes in his own genius. In fact, when a salesman from Syracuse comes to complain about Jim and Dwight taking Binghamton’s clients and ultimately confronts the CEO, California responds, “Harry, there is a time for every decision, pre-determined many years ago. There is no benefit in questioning why this particular decision seems so poorly timed.” From many other executives, this line might seem like a cover-up, but as his actions all along have demonstrated, California really does believe he must have somehow willed this plan into action—even through a debauched revelry. The line between his free-form ramblings about sex and his musings on business and management vanished long before he appeared on the show.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EdhtmV2Lbfc[/youtube]

As in The Blacklist, and just about every production he performs in, James Spader is a joy to watch. As Robert California, he conveys a strange sense of integrity to his character: he is in love with his own vision of the world and has no problem manipulating everyone to conjure what he wants into existence. He is fascinating partly because he is so comfortable aligning his inner thoughts and desires with his public practices. He is someone Nietzsche would be proud of, and whom Freud would professionally delight in. In any case, his leadership style is strangely not wholly unrealistic. Ironically, one of the most apparently verisimiltudinous aspects of The Office is the utter whim with which companies are run. When Andy steals the paper client Prestige from Sabre, the CEO is simply waiting in his office, excited that someone has come to see him. As Andy says, “I could be anyone. I thought I was going to have to convince you.”

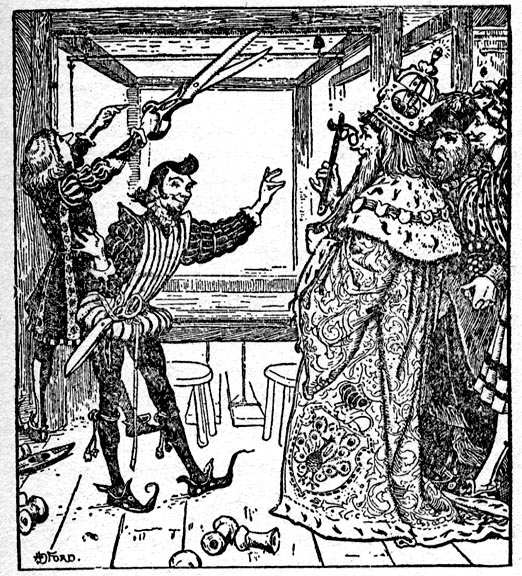

I have come to see in one of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales a parable for how the myth of meritocracy propagates. Two swindlers arrive in a kingdom promising to weave for a vain emperor the finest clothes he has ever worn.

Not only were their colors and patterns uncommonly fine [they said], but clothes made of this cloth had a wonderful way of becoming invisible to anyone who was unfit for his office, or who was unusually stupid.

“Those would be just the clothes for me,” thought the Emperor. “If I wore them, I would be able to discover which men in my empire are unfit for their posts. And I could tell the wise men from the fools. Yes, I certainly must get some of the stuff woven for me right away.” He paid the two swindlers a large sum of money to start work at once.3

Of course, the tale ends with the emperor parading down the street nude, all the denizens of the empire pretending to admire clothes they cannot see—until a little boy shouts out, “But he hasn’t got anything on!”, at which point the town finally admits (together) that they couldn’t see anything to begin with. The emperor, humiliated but too prideful to stop, continues his embarrassing procession.

Andersen’s tale has been told many times, the moral usually articulated as either a warning against vanity or against herd mentality. These morals are not wrong, of course, but another lesson fits the story (you might say) more suitably. Throughout the tale, the emperor, couriers, and citizens believe completely that since they cannot see the fabric, they must be unfit for their positions. Rather than relinquish those positions for the good of the kingdom, however, they feign they belong by pretending to see. The people are unwilling to admit they might be unfit, so they all willingly adopt the fiction that everything is in its right place.

For a little over a decade, our network comedies have effectively been the loud child in Andersen’s tale, gleefully pointing out the Invisible Cloth that is the self-propagating myth of the successful American meritocracy. Let’s join them.

Image Credits:

1. James Spader as CEO Robert California

2. Paul Lieberstein as Toby Flenderson in The Office

3. Emperor Comes to See His New Clothes

Please feel free to comment.

- Stephanie Coontz, “Why ‘Mad Men’ is TV’s most feminist show,” Washington Post, October 10, 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/10/08/AR2010100802662.html. [↩]

- Willa Paskin, “True Detective Does Have a Woman Problem. That’s Partly Why People Love It,” Slate, March 10, 2014, http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2014/03/10/true_detective_has_a_woman_problem_yes_and_that_s_partly_why_people_love.html. [↩]

- Hans Christian Andersen, “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” The Complete Andersen (New York, 1949), trans. Jean Hersholt, http://www.andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/hersholt/TheEmperorsNewClothes_e.html. [↩]

My favorite critique of this from many years back is The Simpsons’ episode with Frank Grimes with Homer as the lazy, underserving slob who is not only successful in the workplace, but also much more popular than the hard-working, conscientious type.

I suspect you’re giving some of these shows more credit than they deserve in terms of their social critiques. Given that Mad Men is enjoyed as a glamorous period piece/ spectacle of privilege, it shouldn’t get the best of both worlds and be assumed to contain a “feminist critique” in any meaningful way beyond being dutifully liberal. (I haven’t watched it in ages, though, so maybe I’m being overly suspicious.)

Mark, I really appreciate the comment. I don’t think I’ve seen that episode, but I can certainly see how The Simpsons would apply.

I do always suspect I’m giving shows I enjoy more credit than they deserve. I know it’s definitely true for The Blacklist. In fact, in my original (longer) version of this piece, I discussed at some length how it is probably not as good as I want it to be. I’m grateful for the possibilities it provides; I’m excited by the critiques it suggests; I do think the creators are trying something daring; but I don’t think it’s succeeding at every level. The writing, for instance, can be quite heavy handed.

That being said, I feel confident that I’m not giving Mad Men too much credit. It’s true that many fans read the show as a glamorous spectacle of privilege: it has inspired retro styles in fashion, alcohol, and misogyny. But I don’t think the show wants its viewers to continually idolize Draper and co. As sympathetic as they can sometimes be as human characters, the ad men lead hollow, pathetic, hypocritical, unhealthy, sometimes sadistic lives—and it’s usually catching up to them. They’re unaware of it, which makes it a bit more pitiable, if no less horrifying. The fact that (admittedly) a great number of viewers miss this point in the face of what Sady Doyle called the spectacle of watching “its characters revel in things that we find unthinkable in 2010” does not make Mad Men‘s overall critique invalid. It just illustrates “our inability to identify misogyny, even on a show that presents it so melodramatically, points to the truth behind sexism, and oppression at large.”

Even though I disagree with Doyle’s larger point (that Mad Men is to blame for veiling our own involvement with the misogyny it depicts), I think she does a superb job of noting how our culture’s obsession with Mad Men reveals its own continuing misogyny. I’d definitely reiterate that too much of Mad Men‘s satire goes unnoticed (Doyle herself does not notice the show’s incessant disapproval of overindulging in alcohol: “To be fair, Mad Men doesn’t hesitate to show the ugly side of these attitudes; they’re not glamorized in quite the same way as, say, drinking Scotch five times a day”), but I’m not sure I would want them to be more heavy-handed about it. One of the great strengths of the show is its subtlety. I’m hopeful that, in time, its example will be used more often in the classroom to emphasize the satire it easily carries.