SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL CONGLOMERATE

Jonathan Nichols-Pethick / DePauw University

Several years ago, working on a student film about local bands in Portland, ME, one of my interviewees told me: “You know what local means? Local means ‘not-as-good-as’ – that’s what local means.” This frustrated yet keen observation referred to the dominance of certain music “scenes” – Seattle, Minneapolis, Austin, Athens – each with their own locally branded sound that had moved out of the merely local and into the realm of the imagined local: corporate-funded nationally or internationally recognized acts with a localized identity. Listeners’ enthusiasm for the merely local bands in Portland, ME had the habit of wilting in the hot glare of an imagined local band from Seattle. As a result, merely local music production was (and is) diminished, rendered nearly invisible.

The same can be said of local television. It is increasingly invisible – its local character increasingly imagined.

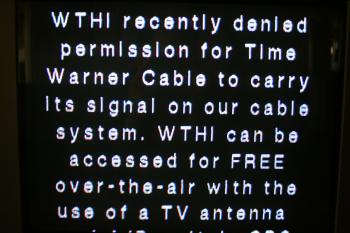

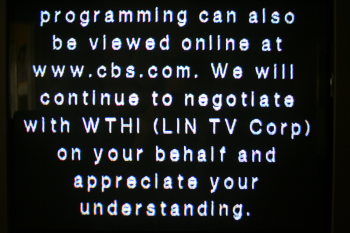

On Thursday, October 2 at midnight WTHI-TV, the CBS affiliate in Terre Haute, IN went dark. Kind of. They were still broadcasting, of course. You could get their signal with a good, old-fashioned antenna, or if you were a satellite subscriber. Anyone tuning in via the local Time Warner cable franchise, however, was out of luck. Viewers were greeted Friday morning by a somber looking scrolling announcement:

WTHI recently denied permission for Time Warner Cable to carry its signal on our cable system. WTHI can be accessed for FREE over-the-air with the use of a TV antenna. Your favorite CBS programming can also be viewed online at www.cbs.com. We will continue to negotiate with WTHI (LIN TV Corp) on your behalf and appreciate your understanding.

What is at least notable (if not surprising) here is the way that this simple strategic message highlights the tensions that structure the relationship between local affiliates, broadcast networks, and cable/satellite MSOs (multiple systems operators) while simultaneously negating them through the aura of inevitability, painting WTHI’s demands as a kind of petty disruption of the natural order of things. In what follows, I would like to briefly trace three arenas in which the changing economics of electronic media are leading to the increased negation and invisibility of local television: ownership patterns, contractual relationships, and the forced infrastructural change to digital broadcasting.

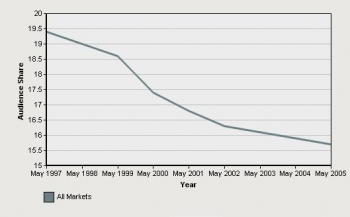

First, and most obviously, the imagined quality of local television is underscored by the fact that ownership of local stations now rests firmly in the hands of a relatively small cadre of “station groups.” According to the latest figures from the Project for Excellence in Journalism, the top 20 station groups own 546 local stations. Stations owned by these groups (of which the major broadcast networks comprise the top 4), can centralize their sales operations and pool capital in ways that allow their stations to run more efficiently and profitably. But even these groups are running into trouble in the wake of the current world financial crisis. According to Broadcasting and Cable, the stocks of Gray Television, Belo, and Nexstar have each lost well above 80% of their value in the last year (Malone 221). These declines in value promise to fuel the increased traffic of stations into the hands of largely unregulated and relatively secretive private equity firms that have little interest in the requirements for or vagaries of localism. FCC commissioner, Michael Copps stated in December 2007, when the FCC approved the sale of over 60 Paxson TV stations to CIG Media, an affiliate of Citadel Investment Group: “We do not know the identity of the investors in this particular fund [series], and we do not know how this fund has treated other companies it has owned in recent years…We don’t have anywhere near the information or context necessary to know whether this change in control will harm viewers” (Marich2). As the identities of owners become less apparent, the operations of local stations become invisible to both communities and regulators.

A second area that points toward the invisibility of local television is the changing contractual relationships that define the daily operations of local stations. Gone are the days when networks compensated local stations for the use of their licensed airwaves. In order to help defray escalating production costs as well as increasingly high fees for the rights to air MLB, NFL, and NBA games, networks have mostly eliminated or, in some cases, reversed compensation agreements, requiring stations to pay networks for access to their programming. Elimination of compensation removes a significant revenue stream from local stations, further fueling the cycle of cost-cutting and centralization that further erodes their ability to engage in merely local production beyond news, and further encouraging private investment. The loss of this revenue stream from the networks also forces stations, regardless of their market power, to seek compensation from cable providers in the form of retransmission fees. As with WTHI, these transactions typically involve the cable operators using their channel space to paint the station as unfairly and greedily seeking money for what is commonly understood as a free service. Perhaps ironically, this process usually involves the cable franchise (Time Warner in this case) positioning itself rhetorically as negotiating on behalf of the local community while highlighting the non-local station ownership (in this case, LIN TV) that, by contrast, does not put the community above its bottom line. Of course, ownership by station groups already moves most local television into the realm of the imagined local, but the new ground-level economies of local broadcasting discussed here work together to further erode both the capabilities of local broadcasters as well as the allegiances of local communities.

Finally, the forced infrastructural change that is the convergence to digital broadcasting also leads toward the imagined local. Most obviously, the switch to digital requires an enormous amount of capital investment beyond the direct means of many locally owned stations, making them ripe for quick sales to station groups and/or private equity firms. In terms of programming, the promise of digital broadcasting has been sold to the consumer in part as the promise of more access to local production (particularly weather and sports) on the additional digital spectrum. The reality of additional programming space, however, turns out to be the promise of more imagined localism in the form of centrally produced weather reports via outlets like NBC Weather Plus or new programming networks such as “Dot2” that are designed specifically for local digital subchannels. These digital networks share advertising with local broadcasters and provide opportunities to insert local news broadcasts into their schedule seamlessly. Trading the potential development and expansion of merely local programming for the imagined local programming of these types of networks represents perhaps the height of invisibility for local programming.

But it’s not just the rationalized operations of large conglomerates and mid-sized media moguls that render the local invisible by encouraging imagined localism. Media studies has been largely blind to the importance of local television. Too often understood as simply “not-as-good-as,” local television productions and operations have received relatively scant sustained critical attention; what it has received has been typically either dismissive or coldly scientific in tone. So what are we to do? If the history of broadcast regulation teaches us anything, it is that localism is impossible to define on a national scale. It is only at the local level that it can be understood, and even then only provisionally. If we’re serious about media reform and preserving some semblance of a commitment to localism in its purest sense – as merely local production – then we will need to confront the slow and steady erosion of local television with something more formidable than sentimental regret. Perhaps we can take hold of this moment and begin talking locally about what local might really mean and how it might be realistically achieved.

Image Credits:

1. Local TV

2. Local Set

3. Author’s screen shot

4. Local Audience

Please feel free to comment.

It appears that, at least in terms of television, the only route to the truly local is through public or city funding as in the case of public access television. Sadly, I cannot foresee a competitive merely local station in the contemporary media industry, comprised of a steadily decreasing number of owners and increasing costs. But, I’m open to suggestions.

u so much for this. I was into this issue and tired to tinker around to check if its possible but couldnt get it done. Now that i have seen the way you did it, thanks guys

with

regards