“Turkish Rambo” Geopolitical drama as Narrative Counter-Hegemony

Marwan M. Kraidy / University of Pennsylvania

Omar Al-Ghazzi / University of Pennsylvania

Arabs and Turks share a historically complicated relationship. After 400 years of Ottoman imperialism over Arab lands that lasted until after World War 1, Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s secularized Turkey and cut linguistic ties with Arab culture. Secularism, nationalism and NATO membership during the second half of the 20th century further distanced Turkey from Arab countries. This changed in 2001 with the rise of the Justice and Development Party (known by its Turkish acronym AKP). Incorporating electoral politics in a pro-business platform reflecting the AKP’s pious and entrepreneurial constituency in Anatolian cities, the AKP has consolidated its power in electoral victories since 2002. In the past decade, Turkey’s forceful foreign policy, public criticism of Israeli actions, increased economic entanglement in the Arab world, and overall rising status, has been discussed via the trope of “neo-Ottomanism.” Despite Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s autocratic tendencies and his government’s worrisome imprisonment of numerous journalists and academics, the AKP appeared to be unshakable until popular demonstrations in Gezi park in Istanbul in 2013 put Erdoğan on the defensive.

After a decade and a half of commercialization and transnationalization of both Turkish and Arab/Pan-Arab television landscapes, Turkish television drama made a strong entrance into the Arab world in the summer of 2008, when the Saudi-owned, Dubai-based, pan-Arab satellite channel MBC first aired Nour [Turkish original: Gümüş] in the summer of 2008, to huge commercial success and public controversy. In light of the historically fraught Arab-Turkish relations, the popularity of Turkish drama series is paradoxical. Elsewhere, we discussed Turkish media’s reception in the Arab public sphere, labeling it neo-Ottoman cool.1 Drawing on the same larger study, here we would like to zero in on what we call geopolitical drama, a genre that enacts a counter-hegemonic narrative that depicts Turks and Middle Easterners as action heroes in global geopolitics.

Geopolitical Turkish dramas, especially those sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, resonated with Arab viewers. The most prominent was Valley of the Wolves, a movie and television series that caused a diplomatic row between Turkey and Israel. Valley of the Wolves was dubbed into the Syrian vernacular and aired by Abu Dhabi TV between 2007 and 2012. It tells the story of a Turkish intelligence officer, Mr. Alemdar, who unravels plots against Turkey and retaliates against foreign conspirators and local collaborators in the name of Turkish pride and Middle Easter solidarity. Some of Alemdar’s exploits occurred beyond Turkish borders, notably in Syria, Northern Iraq, Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, and both films and television featured graphic violence against US troops in Iraq and Israeli troops in the Occupied Territories.

Tensions arose with negative depictions of Israelis and Jews in Valley of the Wolves: Iraq, and Arab media extensively covered the ensuing Turkish-Israeli row. That season centered on what Turks know as the July 2003 “hood event,” when US soldiers led Turkish commandos in Sulaymaniyya, Iraq, at gunpoint, hoods over their heads, into 60 hours of detention. Though the US later apologized, Turkish media condemned the incident as an insult to Turkish pride, triggering anti-US protests in Istanbul and Ankara. The official website of Valley of the Wolves: Iraq described the event as a US bullying attempt.

In the film a Turkish First Lieutenant commits suicide after feeling dishonored by the “hood incident,” leaving a note that compels Alemdar to avenge his colleague. Alemdar travels to Northern Iraq and observes US forces humiliating the local population. Particular scorn is reserved for a US commander called Sam Marshall, who was responsible for the “hood event” and for raiding a wedding party in Northern Iraq and killing the groom and dozens of civilians. An unlikely alliance emerges between the Iraqi bride-widow and Alemdar who together seek revenge against the US officer. The movie depicts Turkish commandos as unequivocal heroes, Americans and Israelis as unmistakable villains. The Arab press described how the musalsal features Israeli agents kidnaping children and Israelis smuggling body parts. In one particularly contentious episode, as Alemdar storms a Mossad post to rescue a Turkish boy, he shoots the Mossad agent, whose blood splatters on the Star of David of the Israeli flag.

Israel accused the series of anti-Israeli and anti-Semitic content, triggering a mediatized Turkish-Israeli diplomatic storm in January 2010, which temporarily appeared to jeopardize the two countries’ strategic alliance. Israel’s deputy foreign minister summoned the Turkish ambassador to Tel Aviv to the Knesset rather than to the foreign ministry, and was made to sit on a low couch, which made him appear on cameras to be on a lower level than the Israeli diplomat. The Turkish flag was also removed from the table. An Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs statement accused the series of showing Jews as war criminals. Furious at Israel’s diplomatic rebuff, Ankara demanded an apology, which it received in the form of a letter to the Turkish ambassador. Pana Films dismissed Israeli accusations, wondering how Israel’s leaders “shell[ing] refugee children hiding under the banner of the United Nations (in Gaza) [but] feel upset when real events are told by Valley of the Wolves?”2

Arab media closely followed the Turkish-Israeli row, casting Turkey as proactive and Israel as reactive. A Lebanese daily opined that Turkey “exposes Mossad as the ghost behind many assassinations and mafias that infiltrate the Turkish state and its agencies,” while a UAE paper wrote that “the Turkish position is brave and resolute in defending Turkish pride and international standing,” and that it would behoove Israel to be more ashamed of the images of the horrific deaths it caused in Gaza rather than of Valley of the Wolves.3 4 Valley of the Wolves: Palestine, released in 2011 in Turkey and Europe, revolves around the Mavi Marmara, the Turkish Gaza-siege busting ship stormed by Israeli commandos in May 2010 who killed 9 Turkish citizens on board, causing an anti-Israeli uproar in Turkey and in the Arab world. In the film Alemdar leads Turkish commandos into the Occupied Territories to liquidate the Israeli commander of the Mavi Marmara raid. When during fighting an Israeli soldier asks Alemdar: “Why did you come to Israel?” He answers: “I did not come to Israel, I came to Palestine.”

Some journalists were skeptical of images of Turkish regional heroism and critical of Turkey’s hypocrisy, on the one hand constructing an anti-American and anti-Israeli self-image, on the other hand maintaining close economic and military relations with the US and Israel. Reflecting Saudi anxiety towards Turkey, the Saudi-owned al-Hayat dismissed Alemdar, wondering “whether the world really needs a Turkish Rambo?”5 Nonetheless, Arab media coverage of the issue bolstered Turkey’s status by framing the series as a tool in regional geopolitics. In reality, the significance of Valley of the Wolves resides less in its artistic or factual merits, and more in its reversal of Hollywood’s routine representations of Arabs and Muslims as villains and its glorification of Turkish power. It is therefore narratively “counter-hegemonic,” though the Arab media’s reading of Valley of the Wolves in purely geopolitical terms obscures economic and cultural factors.

Also, the show’s popularity relates to how attractive Turkish modernity has been to Arabs because it manages to combine a variety of hitherto separate and seemingly contradictory political, economic and socio-cultural elements. Accordingly, Almedar embodies the character of a self-confident, powerful, and moderate Muslim. On Facebook, there are dozens of popular fan pages following and commenting on the show, but also using the show’s symbols to comment on actual political struggles in the region. Alemdar’s image has been used as a symbol for political projects from the Palestinian cause, the Syrian uprising, to the secession of South Yemen. His face is plastered on the flags of different Arab countries and political movements—indicating Arab youths’ eagerness for a politically-potent pop culture symbol.

It is no surprise then that Turkish stars have filled that role. For many Arabs, the rise of Turkey for some time held the promise of literally de-centering Western power in the Middle East, i.e. removing the West as the necessary central mediator between different countries and cultures in the Middle East. In this context, Valley of the Wolves reflects a militarized masculinity. As a martial, fearless, vocal and pro-active commando, Alemdar represents a newly aggressive Turkey, a conqueror whose cultural products depict a growing military might. If the trope of neo-Ottomanism was invoked by Arab pundits concerned about the return of regional Turkish influence (hence the “Ottoman”) but in a different—i.e. diplomatic, cultural, economic—guise (hence the “neo”), then coverage of Alemdar in the Arab press depicts him as a more alluring and muscled versions of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The Arab uprisings now constitute the backdrop for Alemdar’s exploits: In the coming season of the series, the Turkish commando will be in Syria assisting the Free Syrian Army get rid of Assad.

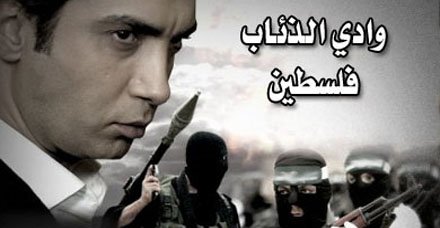

Image Credits:

1. Necati Şaşmaz as Polat Alemdar in a poster for Valley of the Wolves

2. Valley of the Wolves: Palestine promo image

Please feel free to comment.

- Kraidy, M. M, and Omar Al-Ghazzi. “Neo-Ottoman Cool: Turkish Popular Culture in the Arab Public Sphere.” Popular Communication 11 (2013): 17-29. [↩]

- “Valley of the Wolves in the face of Turkish-Israeli tension.” (2010, January 13). Assafir [Arabic]. [↩]

- Hassan, H. (2010, January 14). “Valley of the Wolves at the heart of Turkish-Israeli tension… or is it just a façade?” Assafir [Arabic]. [↩]

- Na‘san Agha, R. (2010, January 15). “Israel and the dead end.” Al-Itihad [Arabic]. [↩]

- Ya‘qub, F. (2011, January 20). “Turkish Rambo.” Al-Hayat [Arabic]. [↩]