Straight Men Can’t Camp: The Politics of “Too Gay” in Behind the Candelabra

Ben Kruger-Robbins / University of Texas at Austin

Early in the final act of Behind the Candelabra, Steven Soderbergh’s Liberace biopic that premiered last month on HBO, the flamboyant entertainer’s lover, Scott Thorson (Matt Damon), announces his distaste for a porn flick playing in the couple’s bedroom. “I just find it repulsive,” he spits to a titillated Liberace (Michael Douglas), aptly providing a summation of the film’s attitude toward gay sex. A disdain for queer eroticism envelops Soderbergh’s detached visual landscape and resonates more explicitly in the uncomfortable performances of Douglas and Damon. As Mike Hale of the New York Times scathingly concludes, “If the impressively assembled Behind the Candelabra is indeed Mr. Soderbergh’s last film, as he has intimated, his final achievement — in part — will have been to get two of Hollywood’s most bankable actors naked together without giving us a very good time.” Soderbergh’s portrayals of gay sex as something ugly and aberrant, I contend, work to undermine the queer potential of his “gay” project and remain consistent with underhandedly homophobic press discourses surrounding the film’s heterosexual stars and director. Furthermore, insinuations that straight artists remain superior judges of gay sensibilities lead me to critique the film on the basis of not only its depictions of gay sex but also on its derision of camp stylization.

Similar to that of Magic Mike, Soderbergh’s 2012 feature about professional male strippers, Behind the Candelabra’s glitzy conclusion sermonizes about the sad destitution beneath sexual adventurism. Unlike Magic Mike, Soderbergh’s “gay” venture divests its conclusion of sexual intrigue. In Behind the Candelabra’s final moments, Liberace’s stage-bound spirit announces that, “too much of a good thing is wonderful,” providing a clear verbal and visual contrast to the film’s preceding series of unfortunate events. Most explicitly, this scene follows an overwrought moment wherein the AIDS-stricken performer seeks Scott’s forgiveness, underscoring the film’s ascription to a politics of sexual shame surrounding its gay characters. While Soderbergh emphasizes repression as Liberace’s ultimate undoing, the film denies his subject any form of erotic pleasure and attributes the narrative’s tragic outcomes to Liberace’s promiscuity and presumed hypocrisy in remaining professionally closeted. In denouncing the sad desperation of the closet without more closely investigating its social creation, Soderbergh equates AIDS with repressed sexuality and the disloyal philandering that inevitably follows. Such logic, paired with visuals that frame both leads’ nude bodies as grotesque (particularly, a close-up of a frail, balding Liberace sans hairpiece and a much discussed close-up of Damon’s artificially bronzed butt), remains consistent with Michael Warner’s discussion of contemporary LGBT politics as embroiled in straight understandings of sexual normalcy.1 Liberace and Thorson, aided by the entertainer’s leering, malformed plastic surgeon (a self-parodying Rob Lowe), resonate as borderline-inhuman monsters deserving of pity, objectified curiosities on display for HBO’s “alternative” viewing audience.2 Since they do not ascribe to homonormative ideals consistent with the current political environment of matrimony and family, Thorson’s and Liberace’s sexual interaction evokes condemnation and laughter (especially during a scene where Liberace offers his partner poppers during sex) rather than even momentary or fleeting eroticism, passion, or joy.

Regarding these portrayals of gay sex, press articles surrounding Behind the Candelabra’s release incessantly highlight Soderbergh’s statement that Warner Brothers rejected his film because it was “too gay” for mainstream moviegoers. In an interview with Mother Jones, the director, whose severed ties with Hollywood and “retirement from filmmaking” received widespread media attention, states that HBO demonstrated a daring sensibility in airing a film that “explicitly displays gay sex”; conversely he announces that executives at Warner Brothers feared that these scenes would diminish Behind the Candelabra’s marketability. Championing himself and HBO, the extended cable channel responsible for airing such gay-themed prestige projects as And the Band Played On (which NBC passed on), Gia, Citizen Cohn, and Angels in America, as exhibiting radically queer sensibilities, Soderbergh indicates an appeal to subversive filmgoers outside the increasingly broad, safe scope of Hollywood. The straight director’s gayer-than-thou proclamation in his Mother Jones interview, however, only renders the controversial sex more staged and obtrusively manipulative; gay male intimacy, as intrinsic to Soderbergh’s anti-Hollywood crusade, resonates as a device to secure HBO’s alternative bona fides and attract socially liberal straight cinephiles rather than subvert hetero/homonormative constructions of sexuality. Regardless of Warner Brothers’ (contested) motives in rejecting Behind the Candelabra, Soderbergh’s and HBO’s insistence that the project was simply “too gay” for theaters resonates as equally insincere.

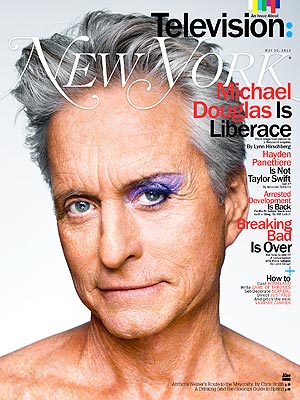

Subtly homophobic statements surrounding the film’s “daring” sensibilities also extend to the film’s leads. Michael Douglas, commenting on costar Damon’s performance, notes, “I just want to commend Matt because I don’t think I would have had the courage at that point in my career to take this on,” prompting a paper as conservative as the Salt Lake Tribune to question why, exactly, a straight actor in a prestige project warrants special commendation for playing a gay character. The self-congratulatory bombast that Soderbergh perpetuates through his “too gay” remarks and that Douglas reiterates in saluting Damon’s bravery contributes to Behind the Candelabra’s straight cooptation of gayness as an overriding press discourse. Focusing intently on the heterosexuality of the film’s leads, a review by Lori Rackl of the Chicago Sun-Times states, “half the fun of Behind the Candelabra is watching these two Hollywood heavyweights deftly tackle roles that could have been career-enders not that long ago,” while Richard Corliss of Time remarks that “the rampantly heterosexual Douglas might seem a stretch as Liberace, but from that first moment on the Vegas stage he nails the character.” Douglas’s subsequent interview with The Guardian, in which he discusses his recent battle with throat cancer as originating from HPV transmitted through oral sex, works to reemphasize his heterosexual credentials and differentiate him from the flamboyant “old queen” in Behind the Candelabra that he “bravely” portrays. Similarly, a New York magazine cover, featured below, visually reiterates the star’s negotiation of the the hetero/homo binary through his onscreen and offscreen performances. Mike Hale discusses this self-awareness in his New York Times review as a detriment to the film’s performances, describing Douglas and Damon as “disconnected and uncomfortable; they push a bit too hard, like a couple of frat brothers putting on a show of fellowship.” The show illuminates a type of straight panic3 that prompts the film’s creative team to embrace gay sex in a self-applauding manner while simultaneously drawing attention to their own heterosexuality.

As a component to the film’s political discourse, press-reviews emphasize the hyper-stylized visual landscape and flamboyant performances as indicators of the film’s “gayness” but repeatedly deny that Soderbergh’s vision constitutes camp. As Willa Paskin of Salon bluntly states, “The most impressive thing about Behind the Candelabra is what it is not: campy.” Tying gay sex into the anti-camp sentiment, she describes the film’s love scenes as transgressing sex to find “compassion” and “love” during exchanges of idle pillow talk and mentions that “many more scenes than you would expect are calm, almost dull.” I agree entirely with Paskin’s adroit assessment, but not as a compliment to the film. Soderbergh’s denouncement of glittering performance and aesthetic excess as masks for emotional rot works to undermine queer pleasure in camp aesthetics. As a way of drawing attention to hyper-heterosexual media tropes and reclaiming agency through alternative viewing and reconstitution, camping remains essential to queer empowerment. Soderbergh’s desexualized and dull ruminations on the dangers inherent in gay sex and performance reflect the sensibilities of a straight auteur rather than a director “too gay” for the Hollywood establishment. In adopting Scott Thorson’s attitude of sexual revulsion, Soderbergh and his company illustrate the dangers of straight men expressing gay love through the lens of their own privilege.

Image Credits:

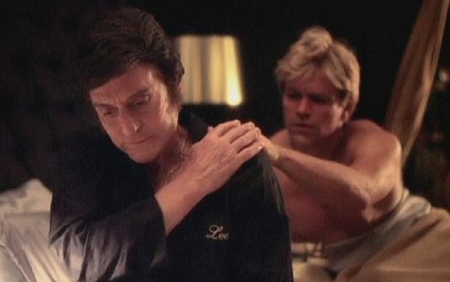

1. Soderbergh and Douglas on set

2. Too much of a good thing is wonderful

3. Damon and Douglas in bed

4. Douglas on the cover of New York magazine

- Warner, Michael. The Trouble with Normal. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA: 1999. [↩]

- Ron Becker discusses gay television programming as concurrent with marketing strategies that target a socially liberal urban-minded professional demographic, or the SLUMPY audience as he terms it. While Becker’s overriding discourse pertains to network television audiences in the 1990s, I would argue that HBO’s promotional strategy for Behind the Candelabra remains consistent with an appeal to straight viewers with “edgy” sensibilities. See Gay TV and Straight America. Rutgers University Press. New Brunswick, New Jersey: 2006. [↩]

- Becker, Ron. Gay TV and Straight America. Rutgers University Press. New Brunswick, New Jersey: 2006. [↩]

Really enjoyable piece Ben!

I especially appreciated your analysis of the rhetoric surrounding the film and I think that you’re right about its lacking in pleasures for spectators looking for either its camp or queer sensibilities.

I do wonder how this film works within Soderbergh’s canon and the mainstream critical discourse surrounding it. For instance, critics have been calling his films cold and “unsexy” for some time, which echoes your statements about this particular film. In other words, I guess I wonder whether his treatment of the subject matter – i.e. is this the case of a hetero director taking the fun out of sex, or if this is more typical of his late works – which tend to subvert their viewers’ expectations, if not disappoint them entirely.

Pingback: Seinfeld’s Web Series and Grading Video Essays: Two New Publications | MediAcademia