Comic Conversations and Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee

Kelli Marshall / DePaul University

I’ve two goals here: first, to explain the rise of a genre cycle I’ve dubbed comic conversations, and second, to submit that one of the most recent products of this cycle, Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, distinguishes itself from similar interview shows—and arguably raises the bar—because of its constant mobility, focus on civility, and high production values.

Over the last five years, an unusual genre cycle has emerged: comic conversations. Shows in which comedians interview or randomly talk to other comedians usually for the pleasure of an audience have erupted both online and on television. Perhaps the three most successful are WTF with Marc Maron, a podcast which currently averages 2.75 million downloads per month; The Adam Carolla Podcast, which recently broke the world record for most downloaded podcasts ever; and The Ricky Gervais Show (with comics Ricky Gervais, Stephen Merchant, and Karl Pilkington), a podcast that held the aforementioned Guinness World Record until Carolla broke it in 2011.

Comic conversations may also be found weekly on these podcasts: Never Not Funny (with Jimmy Pardo and Matt Belknap), Doug Loves Movies (with Doug Benson), Comedy and Everything Else (with Jimmy Dore and Stefane Zambrano), Comedy Bang Bang (with Scott Ackerman and Reggie Watts), The Nerdist (with Chris Hardwicke), and How Was Your Week with Julie Klausner? (significantly the only woman in the bunch).

This new genre cycle isn’t restricted to iTunes though. Cable television and digital networks have embraced the comic conversation as well. Just last year, for example, we saw the release of IFC’s Comedy Bang Bang, a spinoff of the above-mentioned podcast; HBO’s Talking Funny, a roundtable discussion featuring Ricky Gervais, Jerry Seinfeld, Chris Rock, and Louis CK; and Showtime’s Inside Comedy, a series in which long-time Canadian comic David Steinberg talks with Ellen Degeneres, Don Rickles, Martin Short, and Sarah Silverman among others.

There are also Showtime’s The Green Room with Paul Provenza in which panels of comedians discuss their craft (but mostly try to one-up each other), and Modern Comedian, a documentary web series shot, edited, and produced by Scott Moran and distributed on YouTube by PBS Digital Studios. Finally, earlier this summer, I was introduced to the web series In Bed with Joan, in which Joan Rivers invites comedians into “her bed” for a 20-30-minute conversation.

Comic Conversations: Why So Popular?

So why is this current wave of comic conversations so popular? I’ll offer three reasons. First, the shows are cheap to make, especially the podcasts. Aside from a couple of chairs and a relatively quiet space, one needs only a microphone, mixer, and recording software, the latter of which comes with most computers. Moreover, some podcast hosting packages are available for a mere $5.00 a month.

A second reason comic conversations may be so widespread at present is that self-distribution is possible via blogs, websites, RSS feeds, iTunes, and the like. Some have even compared podcasts to television in the 1940s in that it’s “entering uncharted territory but has the potential to rival terrestrial radio” (Halperin). Similarly, because comedians are able to circulate their own conversations, they are able “to take power away from the gatekeepers of culture and put it back in the hands of its creators,” The AV Club’s Nathan Rabin writes.

A final reason these comic conversations have grown in popularity is that comics presumably function as “the punk rockers of today.” In other words, according to comedian Mike Birbiglia and comedian-turned-director Judd Apatow, comics are “saying things nobody really wants to hear but doing it in a way that’s engaging enough to hook you.” (I understand what Apatow and Birbiglia are trying to say, but I’m not sure this differs from what Don Rickles, Lenny Bruce, and/or Richard Pryor have done or did for years.) Still, podcasts and premium cable channels necessitate little censorship; so cursing, uncomfortable banter, and political incorrectness frequently fly through the airwaves.

Along the same lines, many comedians’ personal lives, often destructive, resemble that of “punk rockers,” which, like bear-baiting in the past and car wrecks in the present, creepily attract audiences. Marc Maron, for example, has battled addictions to alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine; he’s twice-divorced, was twice-cancelled by the radio network Air America, and has openly struggled with jealousy toward other comics, his old friend Louis CK in particular. All of this I’ve learned from listening to his podcasts. In sum, comic conversations are popular because most of them are cheap, easy to distribute, and (somewhat) free from censorship.

Enter Jerry Seinfeld…

It was only a matter of time, then, that America’s most well known stand-up comedian would toss his hat into this growing ring. Last summer, Jerry Seinfeld quietly released Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, a weekly web series in which he and a fellow comic are documented driving around Los Angeles or New York, drinking coffee (or tea, in the case of Larry David), and “pouring over the excruciating minutia of every, single, daily event” as Seinfeld’s Elaine Benes would put it. Yes, as Larry David observes at the end of the series’ first episode, “Jerry, you have finally done a show about nothing.”

Distribution and Civility

What’s unique about Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, however, is that it defies virtually all of the potential reasons comic conversations have risen over the last five years. For example, it did not begin freely via iTunes, a blog, RSS feeds, and the like but is distributed via Crackle, a Sony Pictures Entertainment Company—significantly, the same company that owns and distributes syndicated episodes of the TV show Seinfeld.

As well, Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee debunks the notion that comedians function as “the punk rockers of today.” There’s no vulgarity or offensive themes, and the few curse words uttered are bleeped so “you can watch comfortably if your kids are around,” Seinfeld tweets. Like Jerry Seinfeld’s stand-up act and the TV show that bears his name, Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee is not interested in spectacle or shock-value but observational comedy: deliberating with Larry David, for example, about the warmth of a pancake, wearing briefs over the age of 60, and the contemplative nature of a cigar.

Mobility

Finally, Seinfeld’s web series almost certainly commands way more money and involvement than a podcast, a web series like Modern Comedian or In Bed with Joan, and, I’m guessing, even an 8-episode program like Showtime’s Inside Comedy in which two comedians ultimately just sit opposite one another in a nice room carrying on conversations about their craft. In short, virtually every other comic conversation out there is static: two people, two chairs, two microphones or cameras. On the other hand, Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, as its title suggests, is mobile.

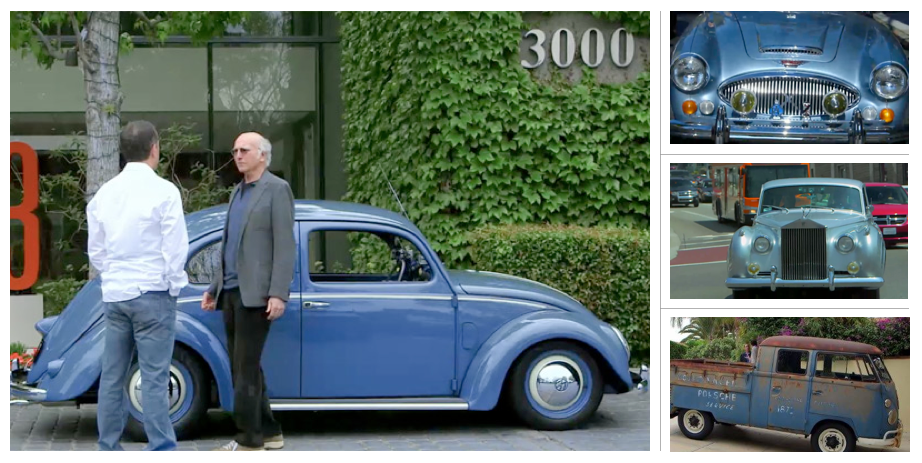

If not using one from Seinfeld’s collection, the web series borrows cars for each episode: the one Seinfeld drives, and then others that follow, precede, or drive alongside him for the exterior shots. Moreover, each car is handpicked to match the persona of the guest. For instance, Larry David gets a 1952 Volkswagen Beetle (“rich guys in a cheap car”), Ricky Gervais a 1967 Austin-Healey, Carl Reiner a 1960 Rolls Royce, and Michael Richards a beat-up 1962 Volkswagen bus.

What’s more, each car must be outfitted with tiny digital cameras and platforms to pick up the comic conversations taking place inside the vehicle. Finally, attentive viewers might notice the cameras and thus camera-operators that follow the comedians when they’re not driving as well as the cameras that must be positioned inside the coffee shops or diners before the two comics enter and then throughout the conversation. In short, much planning and several people are involved here.

Production Values

We might also note the web series’ production values, which arguably surpass those of other filmed comic conversations. I am aware that inserting nouns before the word porn has become a fad, glamorizing or spectacularizing the subject matter at hand, e.g., food porn, disaster porn, kitchen porn (Nancy Meyers’ movies). But that is how many have referred to Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee: as “car porn” or more derogatorily “rich man car porn,” to quote the team from Deadline.com.

For instance, each episode begins with extreme close-up shots of the featured car: a key in the ignition, a taillight, a hood, a side mirror, a speedometer, a bumper, etc. Then, after we’ve been introduced to the car visually, Seinfeld offers in voiceover a summary of its features: make, model, horsepower, etc. See, for example, the opening of the episode with Larry David. And even the beat-up car chosen for Michael Richards gets a glamorized story. (Fans also use the phrase coffee porn when describing the series.)

Conclusions

Whether it’s the cars, the coffee, or the shots of the two comedians’ talking, the production values of Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee—the constant mobility, clarity of shots, editing, sound effects, jazzy nondiegetic music—do distinguish it from others in this growing genre cycle. Compare it to a show like IFC’s Comedy Bang Bang, for example, which sometimes looks as though it was made in the basement of the comedians’ parents, an updated Wayne’s World if you will.

The AV Club’s Steve Heisler is concerned that all the “messiness and humanity” unearthed in many of these comic conversations, podcasts in particular, will be lost if they become more streamlined and commercial. “There will soon be a point when we know too much about comedians to retain any of the magic that initially attracted us to the art form,” he writes.

I disagree, and I think we can use Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee as an example here. With its distribution through a digital Sony Entertainment Pictures Company as well as its embracement of civility and high production values, it does seem more “streamlined and commercial” than most of the other comic conversations out there. And still, 24 episodes have been ordered for Season 2—this compared to the first season’s 10 episodes, which according to Crackle, attracted 10 million unique viewers. No, I don’t think we have to worry about losing magic or overexposure here. Thus, I’ll agree with Heisler’s AV Club colleague Nathan Rabin who claims that, in the case of comic conversations anyway, “familiarity breeds affection, not contempt.”

Image Credits:

1. Comedians in Cars getting Coffee

2. Podcasts

3. Marc Maron

4. Mobility (and cameras)

5. Cars for David, Gervais, Reiner, and Richards

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Two New Publications: Seinfeld’s Web Series and Grading Video Essays | MediAcademia

Pingback: Seinfeld, His Show, and Weak Arguments in the NY Times - MediAcademia

Pingback: Seinfeld, Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, and Weak Arguments in the NY Times | Blog