‘ “War crimes” are defined by the winners. I’m a winner.’ Genocide and legitimizing social systems.

Dr. Rob Leurs / Utrecht University

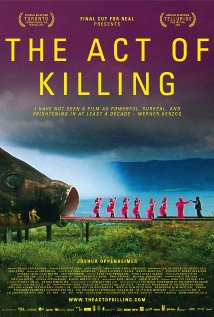

Documentaries are not only interesting because of their content; they can also be works of art in their own right. One of the most striking examples is Joshua Oppenheimer’s recent The Act of Killing1. In this documentary former killers are interviewed about their role in the 1960’s Indonesian genocide: not only do the killers discuss their acts, they also re-enact them in dramatic scenes that resemble B-movies. The two-hour documentary not only gives an impression of the crimes that were committed, but also of how the killers reflect upon their acts. The last element is especially shocking: here the killers are proud of the countless murders committed, in fact they brag about it.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1kssnOoJ93I&feature=youtu.be[/youtube]

These bragging murderers stand in stark contrast to those interviewed in another documentary: Enemies of the People by Rob Lemkin and Thet Sambath2. Here we also get to see murderers whom in the 1970’s contributed to large-scale massacres in Cambodia. But the attitude of these killers is different: they intensely regret what they have done, they suffer from insomnia, and (as Buddhists) believe that they shall never again reincarnate as a human being. Thus, both recent documentaries show killers reflecting upon their past, but interestingly demonstrate two opposing views of upon the crimes committed: pride versus regret. The documentaries show how both attitudes are related to the respective views of the genocidal periods in Cambodia and Indonesia: the Cambodian killers emerged as losers out of a violent decade (the murderous regime was overthrown by Vietnamese invaders), while their Indonesian counterparts remain winners (decades later their allies are still in power). Their respective attitudes, regret vs pride, are related to the outcome: the losers are regretful of their crimes, whereas the winners sense pride. Though their actions are largely the same: they have with bare hands killed countless people, but their reflections upon their acts are opposing. What can a comparison between these two documentaries teach us about large-scale human evil?

Both documentaries have many positive qualities: they attempt to address horrible events from the past, they are unmistakeably works of art, and they intervene in political discussions. Enemies of the People, the documentary about the mass killings in Cambodia, takes on a conventional approach: much research was conducted before filming, the production process itself took a long time, the role of the filmmaker is discussed in the documentary etc. Alternatively The Act of Killing, the documentary about the genocide in Indonesia, takes on a different approach by not adhering to conventional rules: it does not present the victim’s point of view, fiction and non-fiction are intertwined, and only minimal historical context is presented. But it would be incorrect to state that the The Act of Killing therefore offers little insight, on the contrary: it tells us a lot about killers, however in a different way. I shall now expand upon this: the Cambodian ‘losers’ versus the Indonesian ‘winners’ – the Cambodian killers belonging to a group that emerged from history as losers, while their Indonesian counterparts prevailed as winners. With this I aim to say something about the roots of genocide, namely the genocidal system in which perpetrators operate.

The attitude of the killers, their psychological state, is sharply reflected in their statements. The Cambodians respond as you hope they would do: they bitterly regret their past deeds and are full of guilt. As one of the killers states3 :

“I do not know what I’ll be reborn as in the next life. How many holes of hell must I go through before I can be reborn as a human being again? I feel desperate, but I do not know what to do. I will never again see sunlight as a human being in this world. This is my understanding of Buddha’s Dharma. I feel desolate.”

The attitude of the Indonesian killers starkly contrasts with this. They do not respond in the way that we are used to from Hollywood movies: evil is not rejected. Even more, it is condoned as is demonstrated by one of their statements4:

“So maybe the Geneva Conventions [amongst others prohibiting the killing of civilians in wartime] are today’s morality, but tomorrow we’ll have the Jakarta Conventions and we’ll throw away the Geneva Conventions. ‘War crimes’ are defined by the winners. I’m a winner. So I can make my own definition. I need not follow the international definitions.”

These psychological differences do not come out of nowhere: they are related to the state of their respective societies. The Cambodian perpetrators have no regime to fall back on: their political party is gone, the international legal order (in the form of the Cambodia Tribunal) is prosecuting their former leaders, and the dominant religion in their society is incompatible with their deeds. In a society that disapproves of their past actions in all kinds of ways (politics, law, education etc.), murderers can only talk with regret about their deeds. How different is that in Indonesia: there, the murderers are winners. Not only in political terms: media (in the form of a newspaper in this documentary), the army, a powerful militia (called ‘Pemuda Pancasila), law etc. condone the genocide in which these men were executioners. In a more general sense: psychological attitude is partly rooted in its context, which is in this case the structure of the respective societies. In Cambodia the legitimizing context for mass killings has fallen away, while in Indonesia the legitimization of the genocide is still present. That calls for focus on ‘legitimizing context’, because this not only tells us something about the current (psychological) attitude of perpetrators, but also about how legitimization works.

A society consists of many institutions and discourses, e.g. politics, entertainment, media, law, religion, economics, etc. These aspects of society are interrelated: they give each other power, and in turn derive power from one another. Together they tell us what is normal, i.e. how to think and live. If the social institutions and discourses strongly coincide, then rules for thinking and living become compulsory, even if outsiders would find them ethically objectionable5. The coinciding institutes and discourses can then become a homogenizing system, with the risk of enforced (and sometimes violent) homogenization. Thus, genocide (but also other large-scale evil like apartheid, gendericide, and ethnic cleansing) is more likely to occur within such a compulsory system than in societies where social discourses and institutions are separated from one another and where they are able to correct each other from a relatively equal position6. Chances that large-scale killings take place (and the perpetrators’ reflections on this afterwards) thus depend on the kind of society in which they are devised: if there is a legitimizing context, there is less inhibition. In other words: genocide is not just an event but emanates from a social system. Only when that system falls away, as in Cambodia, moral correction can take place.

What can and should we do with the knowledge that genocide (and other large-scale evil) depends on a legitimizing context, a legitimizing social system? Two things. Firstly, we must, retrospectively hold murderers accountable (in the form of trials or truth commissions) whereby we not just focus on individuals: we must hold a society as a whole accountable, including its institutions and discourses. The purposes of this is the dismantling of legitimizing systems where they still exist (as in Indonesia), the creation of a correct view on the past in the case of systems that have fallen away (thus trying to answer the question: ‘How the hell could this have happened?’) as in Cambodia, and in both cases: contribute to justice. Of course this can never result in actual justice, as for every murder justice can only be symbolical and cannot undo the past. Secondly, it can warn us for future large-scale evil. In addition to an assessment of legitimizing social systems of past and present (for systems that still exist), it works preventively: it shows us that we must strive for societies with relatively separated social discourses and institutions, so that any incitement to large-scale evil gets as little legitimization as possible. Precisely because of the opposite attitudes of their respective protagonists, The Act of Killing and Enemies of the People are powerful lessons in the construction of (dis)functioning nations.

Image Credits:

1. The Act of Killing Movie Poster

2. The Act of Killing Movie Still

Please feel free to comment.

- The Act of Killing. Dir:. Joshua Oppenheimer. Final Cut For Real, 2012. For more information, see http://theactofkilling.com. [↩]

- Enemies of the People. Dirs:. Thet Sambath & Rob Lemkin. Old Street Films, 2009. For more information, see http://enemiesofthepeoplemovie.com. [↩]

- Enemies of the People. Citation from original subtitles [↩]

- The Act of Killing. Citation from original subtitles. [↩]

- This of course raises the question whether something is ‘evil’ when people within a certain constellation approve of it, and only outsiders disapprove. For a good introduction, see Neiman, S. (2002). Evil in modern thought. An alternative history of philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [↩]

- This is consistent with Ernesto Laclau’s idea about the heterogeneity of ethical concepts resulting from a contingent relationship between the ethical and the normative; if ethical and normative orders would fully coincide, there would be totalitarianism and thus a greater chance of a broad legitimization of what is understood by outsiders as horrors. Laclau, E. (2004). Ethics, normaticity, and the heteronomy of the law. ” In: Cheng, S. (Ed.). Law, justice, and power. Between reason and will. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [↩]