Afterthoughts on Martin Luther (1953) and Christian American Cinema

Dan Chyutin / University of Pittsburgh

The recent publication of “‘A Remarkable Adventure’: Martin Luther and the 1950s Religious Marketplace” marks the culmination of a project that originated in 2008, as I was just starting out in the doctoral program at the University of Pittsburgh. As part of a graduate seminar, I was asked to write an essay that serves as an example of film historiography. I decided to use this occasion to experiment in using and writing about archival materials. The only difficulty was that my area of scholarship, then and now, has been Israeli cinema, and there were no relevant archives in this field on American soil. Out of sheer frustration, I began leafing through old volumes of Hollywood Quarterly in search of a paper topic. Finally, I came across LA-based writer Michela Robbins’s brief article “Films for the Church” (Winter 1947/8), which explored the recent acceptance, by institutions of organized religion, of cinema “as a new and powerful form of education and evangelism” (178)1 . Since I was unaware of American Christian filmmaking up to that point, I decided to investigate it further, ultimately discovering the peculiar case of the church-produced film Martin Luther (Irving Pichel, 1953) and its surrounding historical documentation (found in the Archives of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Louis de Rochemont Papers/American Heritage Center). Working with these primary documents not only provided me with insight into a community of craft and ideology of which I knew nothing, but also helped foster my own interest in Israeli filmmaking from a Judaic perspective. And though my doctoral work rarely allows me to deal with the study of Christian media nowadays, I find that my brief introduction to this area continues to enrich my understanding of the intersection of film and religion, which stands as the axis mundi of my scholarly world.

Yet I did not intend to use this space only to muse on the place this essay occupies in my intellectual development. Rather, this brief post has also provided me with the opportunity to inquire into scholarly publications on Christian cinema that have come out over the two years since I first submitted my paper for review. The most pertinent publication to emerge in this context is undoubtedly art historian Esther P. Wipfler’s Martin Luther in Motion Pictures, which was published in Germany by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Press. Wipfler’s book discusses various filmic representations of Luther in different national and historical contexts in an effort to chart out the changes in his public image. Its section on the 1953 Martin Luther complements my own essay in interesting ways. Wipfler’s account provides important additions to mine, especially in terms of the film’s place in the history of Luther films, its impact on international audiences, and the accuracy of its content. My account, on the other hand, significantly adds to Wipfler’s through its focus on the film’s place within postwar American interdenominational politics and its elaborate discussion of the meeting of religion and media, especially in relation to how it affects issues of authenticity, aesthetic strategy, and production and distribution practices. Together, these two writings now provide a more complete picture of the 1953 Luther film, and will hopefully draw the necessary attention to its enduring importance.

The value of the aforementioned texts notwithstanding, the most important contribution to American Christian film scholarship over the past two years has arguably been Terry Lindvall and Andrew Quicke’s Celluloid Sermons (NYU Press). In this volume, the two film historians, who have long exhibited an interest in Christian cinema, provide a comprehensive chronological overview of American Protestant filmmaking from 1930 to the late 1980s, when the rise of videotape technology heralded the decline of the church film market. What emerges from their vivid account is the portrait of a thriving industry that negotiated the pressures of religious tradition and secular modernity while attempting to adapt the Word of God into a filmic vision. Often considered backward and naïve, the Christian American film industry has rarely been addressed in scholarly writing on American cinema, and never in book-length form. Yet a detailed inspection of Christian films from the era reveals an incredible diversity of narrative strategies, formal modalities, genre formations, and distribution and marketing techniques that demands more serious academic consideration. In this respect, then, Lindvall and Quicke’s project stands as a seminal effort of recovery, unearthing a forgotten chapter of American film history while keeping alive the memory of its leading figures—people like James K. Friedrich, Carlos Baptista, Irwin Moon, Sam Hersh, Ken Anderson, Billy Zeoli, Paul Empie and Louis de Rochemont—for the appreciation of future generations.

This being said, if I could note one major element that is missing from Lindvall and Quicke’s account, and from the other accounts mentioned in this entry for that matter, it is a meaningful discussion of “spiritual” film aesthetics. Scholarship in cinema studies has rarely engaged film aesthetics from a spiritual perspective, and when it has, discussions have focused on a single form: an austere style which does not exploit the medium’s expressive potential to create a plentiful image of the world but rather seeks to strip reality to its bare bones. While this style fits nicely with the work of canonical spiritual filmmakers such as Robert Bresson and Yasujirō Ozu, it can hardly be applied to American Christian films. Does this mean that the styles of these films are incapable of orchestrating encounters with the ineffable? In the case of Martin Luther, for example, an aesthetic that combined documentary and melodrama was used to assert the impression of compelling historical realism, and consequently seemed more oriented towards physical than metaphysical reality. Yet could we not find in this depiction of the “reality” of Luther’s life thresholds towards the Transcendent? Though its melodramatic aspects do not conform to the traditional standards of spiritual stylistics, it may be argued they uniquely flesh out those facets of Luther’s reality which resonated with the Sacred. As Rudolf Otto explained, in his 1927 classic The Idea of the Holy, the “purely numinous elements in Luther’s religious consciousness” were found exactly in his moments of non-rational excess, “in his battles with ‘desperatio’ and with Satan, in his constantly recurring religious catastrophes and fits of melancholy, in his wrestlings for grace, perpetually renewed, which bring him to the verge of mental disorder.” In light of this assertion, is not melodrama— so typical of American Christian film—a style more suitable for the depiction of Luther’s “profoundly non-rational strain of ‘religious awe’”2 (102) than Bressonian asceticism?

Answering these and like-minded theoretical questions will be the next important challenge for Christian American film studies. Without confronting this challenge, scholars may unwittingly perpetuate the definition of Christian cinema as stylistically backward, and thus as unworthy of serious study beyond its status as a historical curiosity. Yet if an attempt is made to forge a response to these queries, we may well find that Christian films have much to tell us, not only about their own history, but about the nature of the moving image itself.

Image Credits:

1. The Martin Luther (1953) World Premiere at the Minneapolis Lyceum Theater, Image Courtesy of the Archives of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

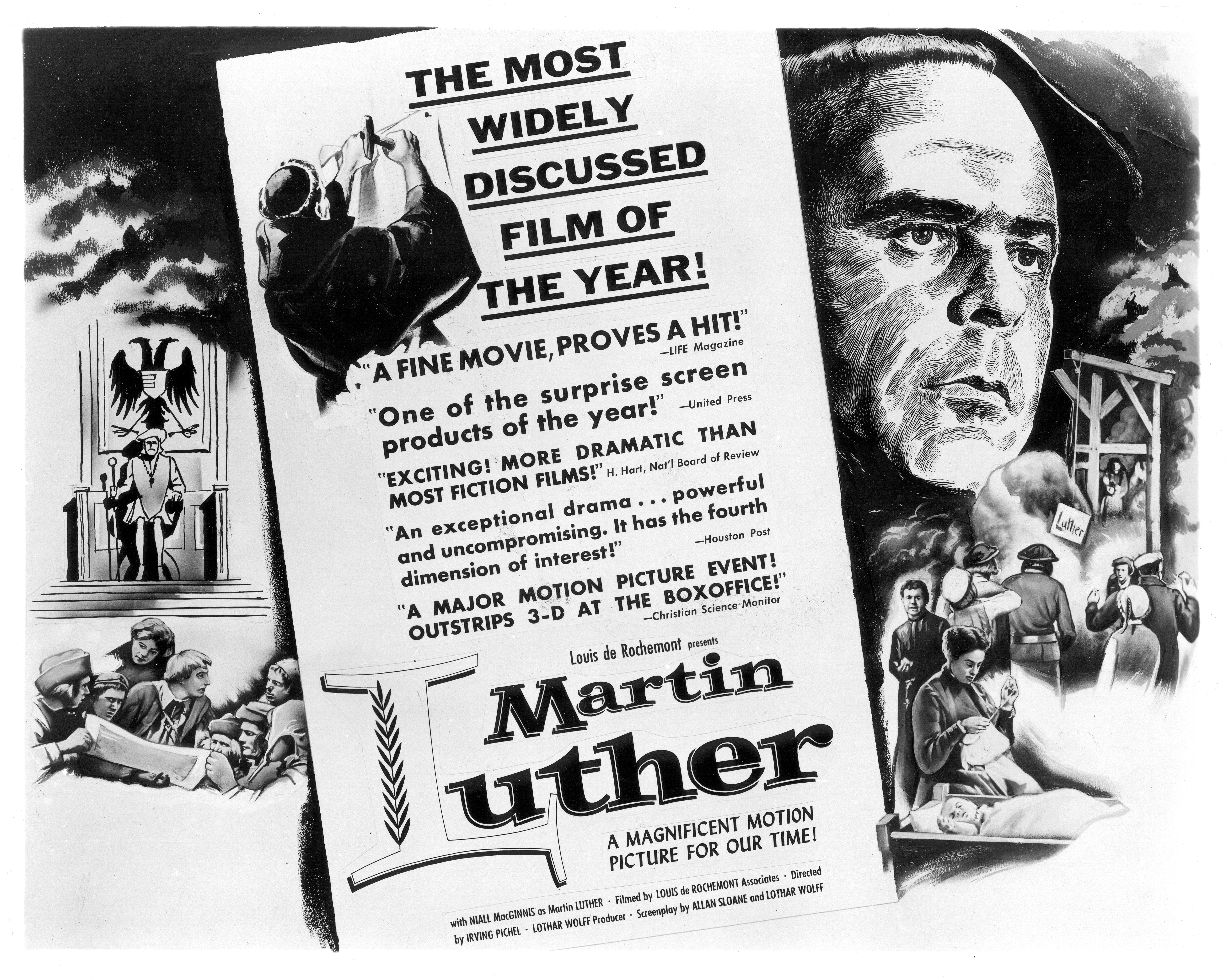

2. Publicity Ad for Martin Luther (1953), Image Courtesy of the Archives of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

3. Martin Luther Producers Paul Empie (Right) and Louis De Rochemont (Far Right) Receiving a Plaque from The Christian Herald, Image Courtesy of the Archives of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

4. Actor Niall MacGinnis Striking a Dramatic Pose as the Eponymous Protagonist in Martin Luther (1953), Image Courtesy of the Archives of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

Please feel free to comment.