Dexter, Straight Homosexuality, and the Normalization of the Psycho

David Greven / University of South Carolina

The hit Showtime series Dexter began in 2006 and will commence its eighth and final season in June 2013. Based on a series of novels by Jeff Lindsay, the series stars Michael C. Hall, who was so memorable as David, the rigid, semi-closeted brother in a funeral home-family on the HBO series Six Feet Under, in the title role and Jennifer Carpenter as Dexter’s adoptive sister, Debra Morgan (“Deb”). The chief gimmick and hook of the series is that Dexter is a serial killer who kills other serial killers. Dexter’s day job as a forensic blood splatter analyst in the Miami Metro Police Department, leads him to investigate the crimes and the criminals by day that he punishes privately by night. On Dexter, crime is a family affair—Dexter’s detective sister Deb is the Captain of his department, and Dexter’s adoptive father, Harry (James Remar), was a cop who rescued the infant Dexter, crying in a pool of blood, from the scene of his mother’s brutal murder via chainsaw. (The frequent flashbacks of this event evoke both The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Scarface, which features a chainsaw shower murder). Harry, who appears here in ghostly flashbacks and as a figment of Dexter’s mind, as did the dead father on Six Feet Under, sensed early on—or did he himself implant?—Dexter’s killer instincts. Harry transforms his would-be serial killer son into a different kind of serial killer, one who kills other serial killers instead of innocent people (or animals, as the young Dexter had).

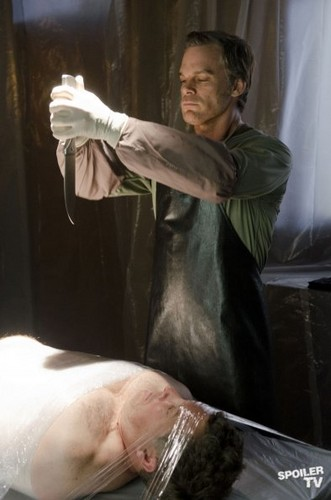

Evoking Hammurabi and the Bible, Harry’s Code, as Dexter calls it, governs his action. The Code dictates that Dexter may only kill an evil person who has himself murdered others. Further evoking the Biblical texts, such as Leviticus with its strict hygienic rules and sub-rules, Harry’s Code dictates the proper forms of killing and disposing of these vile bodies. Everything is stream-lined here, murder baroquely ritualized and pristine. Covered from the neck down in a tightly binding Saran Wrap-sarcophagus, the killer-victims lie on a table much like that in a doctor’s examining room, surrounded by the pictures Dexter has arrayed around them of their victims and of the brutal violence they inflicted. Forcing the killer to recognize, at once, his victims’ humanity and his own inhumanity precedes Dexter’s ritualistic murders of the culprits. With one fell, practiced swoop, he drives a long, silver blade into their hearts, invariably producing the odd effect of one stream of blood pooling on the plastic. This is murder as ritual sacrifice to the patriarchal gods still sternly, if ever more distantly, presiding over our fallen age (one episode in the seventh season made the link to classicism explicit with the killer-of-the-week’s Minotaur-like labyrinth); murder as theater, a staged and stylized tableau. Harry’s Code provides the last bastion of order and discipline in this chaotic present. Dexter is the dutiful son saved from his own perversity by adherence to the symbolic order.

As I have argued elsewhere, the 2000s have radically refashioned the chief image of non-normative masculinity in American media, the “Psycho.” Psychos like Robert Mitchum’s Max Cady in the 1962 Cape Fear or the cannibal psychiatrist serial killer Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) oppose normative structures like families, marriage, and middle-class morality. The Psychos of the first twenty-first century decade have not followed suit. Indeed, rather than stand as the enemy of the family and the normative, they have exuded a penchant for upholding family values, a disturbing trend for characters one might imagine to be vehemently opposed to either families or values.1

Dexter is the exemplary Family Values Psycho. He maintains his most passionate relationship with his sister, Deb, and with his new family, his wife Rita (Julie Benz) and her children from a former marriage. (Rita was killed by the Trinity Killer, played superbly by John Lithgow, at the end of the fourth season; in the seventh season, Deb, an anguished silent partner made aware of her adoptive brother’s proclivities, has not only fallen in love with him but, by the end of the season, assisted him in one of his killings – a killing that violates Harry’s Code, at that.) One of the most affecting aspects of the first season of the series was its thematization of Dexter’s alienation, which Rita’s own—she had been in a physically and abusive relationship with her ex-husband, and in the first season seems as outwardly remote as Dexter claims to feel—deepened. As he describes in the noirish voiceovers that saturate each episode, he feels like someone with no feelings, and subsequently as someone who must perform his own humanness for others. More and more, these affecting aspects of the series have diminished, with Dexter becoming more and more human, especially, a loving father. Paradoxically, his warm parenting leads him to fall out of step with Harry’s Code, Harry appearing before Dexter to warn him against developing personal ties.

Dexter is a compelling series driven by the deft performance of Michael C. Hall in the lead and the raw, unrelenting emotional anguish of Jennifer Carpenter as Deb. Yet its popularity relies upon a grotesque hypocrisy, a desire to indulge in bloodletting while maintaining a veneer of do-gooder benevolence—the ultimate American fantasy. The various media phenomena spawned by the series, video games and chat rooms with names like “Dexter’s Disciples” and “Dexter’s Kill Room,” reveal far too much about the take-away lessons of the show.

The image of the serial killer as a monster depends upon mythologies of not only his potential for violence but also his sexual incompetence, blankness, or some other form of dysfunctionality, as the example of Dennis Rader, the infamous Kansan serial killer known as the BTK Killer, evinces. These aspects of the serial killer dovetail with cinematic representations of the killer in the slasher genre in particular, whose sexuality, as Carol J. Clover acutely observes, is problematic not because of its perversity but precisely because it cannot achieve functionality on any level.2 Perhaps most surprisingly of all, the sexual dysfunction with which killer manhood is associated, broadly and historically speaking, in American culture finds a surprising rebuttal in Dexter.

Dexter is initially presented in season one as sexually inviolate; his relationship with Rita is non-physical and, moreover, she herself, as a result of her abusive relationship with her ex-husband, finds sexuality traumatic. Yet Dexter and Rita do have sex—Dexter seems to be having it for the first time—and from there the series begins to present a radically different version of its protagonist. Far from being sexually dysfunctional, this lean, buffed, attractive, accessible serial killer whose efforts would appear to benefit the common good has no trouble at all, once he has sex with Rita for the first time, performing sexual intercourse, and goes on to do so, and with every indication of skill and success and also demonstrable arousal for both parties, with a variety of women throughout the series, ranging from the femme fatale English woman in the second season to the horribly abused Lumen in the fifth season. Lumen (Julia Stiles) was tortured and gang-raped by a group of male friends led, in their horrific abuse of women, by a self-help guru, the chief villain of the fifth season, whose ferocious male-empowerment mantra is “Take It!” In one scene, after Dexter and Lumen kill one of her attackers, they make love, as if the shared gift of murder has purged her of trauma and them of awkwardness. The gift of ecstatically functional sex rewards Dexter for his outlandish but socially beneficial form of serial killer justice. It’s almost as if serial killer energies, when directed toward the larger societal good, can produce a version of American white manhood that is more desirable, more functional, than many others out there.

To be fair to the series, its seventh season (2012) is an admirable attempt at a moral reckoning, far too late in coming but nevertheless admirable. It focuses on Captain María LaGuerta (Lauren Vélez)’s efforts to exonerate Doakes for Dexter’s crimes and to prove that Dexter is The Bay Harbor Butcher of Season 2. (In the first two seasons of the show, the second especially, Dexter’s nemesis is a black detective, Sergeant James Doakes, played Erik King, who senses that there is something not quite right about Dexter. Dexter imprisons Doakes at one point, but it is the raven-haired English woman who kills him.) In the shared murder, by Dexter and Deb, of LaGuerta in the final episode of the season (“Surprise, Motherfucker!” airdate December 16, 2012), the series finally took its own premise and the moral perfidy of its protagonist—which engulfs the once-morally-upright Deb—seriously. Dexter’s killings, Code-bound or not, are morally unjustifiable. Deb cannot participate in them without losing her soul in the process, no matter how malevolent the usual run of victims might be. In the killing of the inconvenient LaGuerta, Dexter and Deb both irredeemably cross the line even of the vigilante ethics that dominate the series.

The seventh season also does something actually quite rare for genre series – it features an explicitly gay character in a prominent role. The odd rapport between the deeply brutal but surprisingly eloquent and thoughtful Isaak Sirko, a Ukranian crime boss played by Ray Stevenson, and Dexter takes the series to a new level of probity in its analysis of the motivations for and the varieties of evil. Moreover, as played by Stevenson, Sirko, while the conventional gay-killer, also offers an unconventional version of this type, there being nothing stereotypically gay about his character. Indeed, Sirko’s love for a young man who also works for the crime ring is represented as his one redeeming feature. Before meeting Sirko, Dexter killed Sirko’s lover once he discovered that he had killed a young woman; Sirko vows to kill Dexter, but the two end up being unlikely allies and even something like friends, with Sirko offering Dexter caring advice about how to live life to the fullest before he dies.

Significantly, even though a bond develops between the gay Sirko and Dexter, there is no homoerotic tension between them whatsoever. Indeed, we never Sirko him with his handsome homicidal young lover, never see their interactions even in flashback, and only have the evidence of Sirko’s declarations of ardent love to go on. So, ultimately, even when homosexuality is explicitly represented in the series, it is an obscure phenomenon. Sirko, and the series handling of the character, exemplifies the new form of “straight homosexuality,” which represents a willingness to depict major characters as gay without typing them as anything other than heterosexual. The characters are gay in name only.

As with so very many genre productions, however, implicit and coded and allegorical representations are a different matter. There is a palpable homoerotic tension in the series, and it chiefly emerges within the scenes of Dexter’s interactions with non-white men, like Doakes, who is, at once, justifiably and irrationally suspicious of Dexter; with Senior Assistant District Attorney Miguel Prado (Jimmy Smits) in the third season, with whom Dexter believes, for a time, that he has forged his first real friendship; and, especially, Dexter’s biological older brother Brian Moser (alias Rudy Cooper, “The Ice Truck Killer,” played by the hypnotically handsome Christian Camargo), the main villain of the first season and Dexter’s dark double.

The almost aching homoeroticism of the relationship between Dexter and Brian Moser undergirds and deepens all of Dexter’s relationships with other men, especially non-white men. As played by Carmargo, Brian Moser (who returns in dream/fantasy form, like Dexter’s father, in a later season for one episode) also suggests an ethnic masculinity. (He resembles the Hispanic Steven Bauer, best known as Al Pacino’s right-hand man in Scarface). Given that Dexter is, among other things, a fantasy of a white male potency that can triumph over the perceived hyper-potency of the non-white—much like James Fenimore Cooper’s “Leatherstocking” novels featuring Natty Bumppo, his male Indian family, and his male Indian enemies—its homoerotically charged racialized masculinities and racial conflicts return us, as so many 2000s works do, to the earlier scene of American history, to Cooper’s vision of a white American masculinity that rejects sex in favor of what Leslie Fiedler called the true marriage of males, the interracial union of a white man and a non-white man that represents a break (for the white male) from the demands of the private sphere of woman, family, and the home. In Dexter, however, Cooper’s model is radically renovated. Dexter successfully achieves functional heterosexual desire and prowess early on in the series.

Straight homosexuality allows for the representation of gay characters without the complexities and difficulties of introducing non-heterosexual characters into often quite heterosexist narratives would entail. It also allows interactions between male characters to be tinged with, even steeped in, homoerotic “tension”—as the scenes between Dexter and his serial-killer brother Brian Moser are—without there being any real threat of homosexual “behavior.” As I discussed in my Flow article on The Walking Dead, we have entered a new era of homoerotically charged but resolutely heterosexist depictions of masculinity, heterosexist in that the males are always presented as unquestionably heterosexual because the question of queer desire can be broached. (It is inconceivable that any of the male protagonists of series like The Walking Dead, Breaking Bad, or Dexter could ever have their heterosexuality questioned.) Straight homosexuality allows a series to register and acknowledge the undeniable, visible presence of queer sexuality in our current moment without succumbing to its apparent seductions.

Image Credits:

1. Dexter’s ritualistic kill

2. Harry’s Ghost

3. Dexter’s sister, Deb

4. Defying the Code

5. Gay Sirko

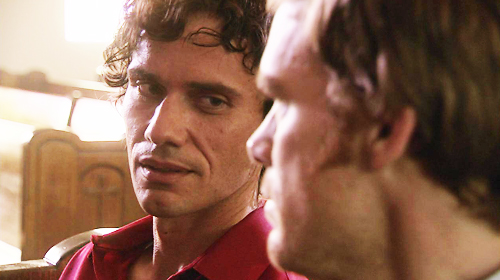

6. Brian Moser and Dexter

Please feel free to comment.

- See David Greven, “American Psycho Family Values: Conservative Cinema and the New Travis Bickles,” Millennial Masculinity: Men in Contemporary American Cinema, ed. Timothy Shary (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2012), 143-162. [↩]

- Writing about slasher films generally and Jonathan Demme’s film The Silence of the Lambs (1991) specifically, Carol J. Clover finds that “in the long and rich tradition in which he [Silence’s villain, Jame Gumb] is a member, the issue would appear to be not homosexuality and heterosexuality but the failure to achieve a functional sexuality of any kind.” See Clover, Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1992), 233. [↩]

Terrific article. I think the most downright hilarious example of a non-performative queer

relationship, a relationship that only makes sense that way, a relationship so overtly

non-hetero that the network has banked on it in marketing is the love affair between

Boyd Crowder and Raylen Given in JUSTIFIED.

Very well written article! I think the writers of Dexter did a terrific job writing Ray Stevenson’s character, Isaac Sirko. Sirko’s homosexuality was very modest and not flamboyant like some television shows have been doing to show to the world that they are relevant to our society. Dexter forms relationships with people who are broken or have suffered a horrific event in their life. Their broken personas attracts Dexter because he sees himself as broken, this explains why we see Dexter form close relationships with Rita, Sirko, and Hannah McKay. Dexter may not realize it, but he asserts himself into their lives as the problem-solver. He continuously risks his life in hopes to return their lives to a sense of normal. The “straight homosexuality” term you discuss perfectly describes the relationship between Sirko and Dexter. Because Sirko’s homosexual representation was more subtle, it allows him and Dexter to form a close relationship without adding any sexual tension to their relationship.

This was a great article,Having never watched Dexter I feel that by reading this I understand a character that I haven’t even seen yet. The Straight homosexuality that you write about, is also present in another show that is getting hug attention from its fans. NBC’s Hannibal also a male driven show has the aspects of homoerotic nature in it. Though you know all of its characters are straight, Hannibal has an unflinching attraction to Will Graham, but we never doubt that each man is straight. This series has also painted Hannibal in a some what normal light. As a man who is desperately trying to have friends in his life, but the homicidal nature that he has gets in the way. I think Dexter has allowed the tv watching public to change its perceptions of the crazed serial killer, it has given them something that we all know they lack. It has given them back there humanity