Altermodern Literacy: Netflix, Apple TV, YouTube, and Cutting the Cord

Ralph Beliveau / University of Oklahoma

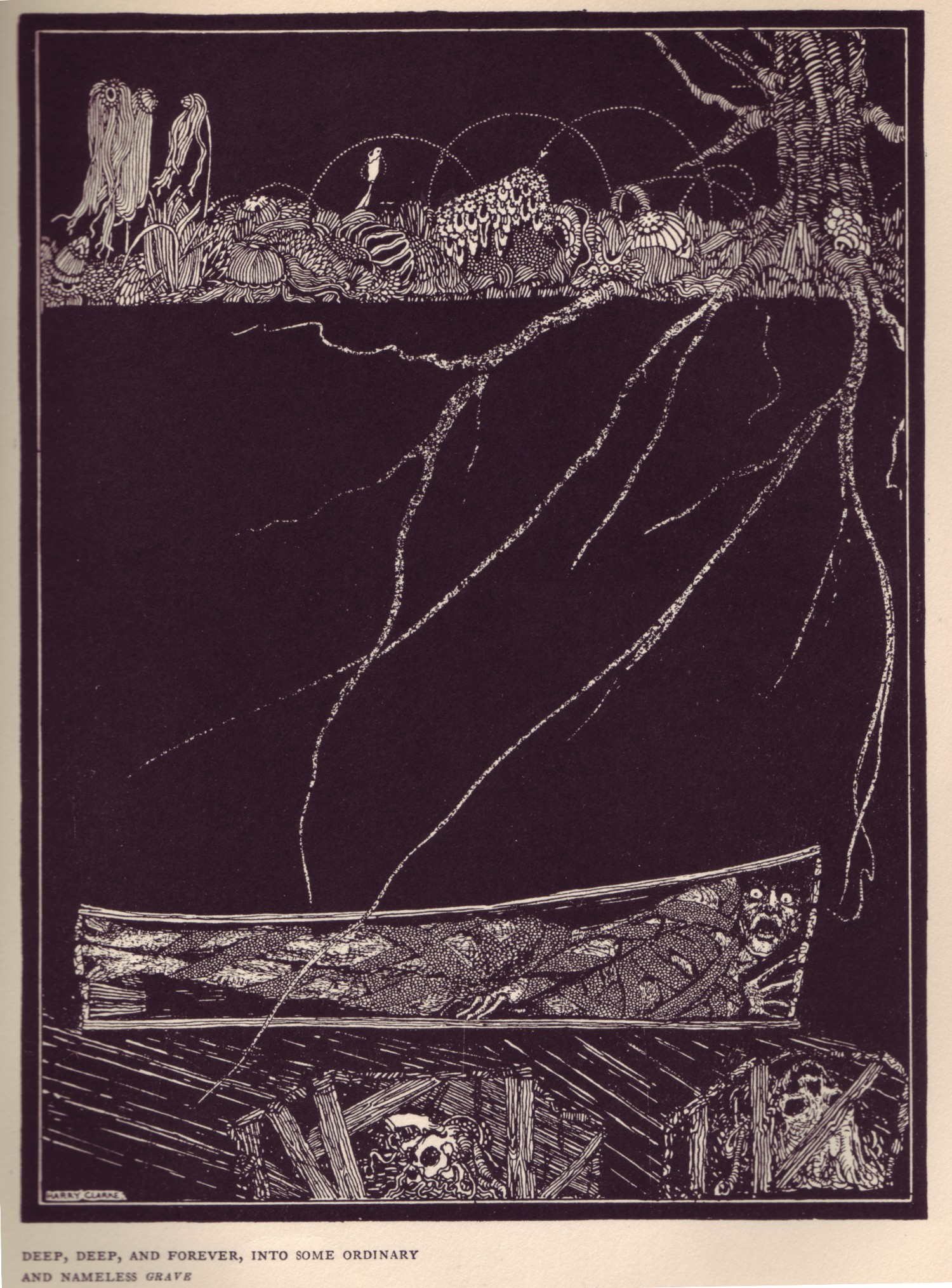

I looked; and the unseen figure, which still grasped me by the wrist, had caused to be thrown open the graves of all mankind, and from each issued the faint phosphoric radiance of decay, so that I could see into the innermost recesses, and there view the shrouded bodies in their sad and solemn slumbers with the worm. But alas! the real sleepers were fewer, by many millions, than those who slumbered not at all; and there was a feeble struggling; and there was a general sad unrest; and from out the depths of the countless pits there came a melancholy rustling from the garments of the buried. And of those who seemed tranquilly to repose, I saw that a vast number had changed, in a greater or less degree, the rigid and uneasy position in which they had originally been entombed.

-Edgar Allan Poe, “The Premature Burial”

Floating above, at night, and all the roofs of the houses become transparent. Picture the vast numbers of glowing video and computer screens. Radiant. Most showing images of something past, pictures, sounds, words. Are we watching decay? Disintegration? Is unity destroyed, broken down into constituent parts?

Premature burials are more frequent than we might think, Poe suggests, and we might be wise to check and see. For example, the invocations of “postfeminism” and “postrace” have often appeared…and appeared often. They appear, suggesting a burial; but, out the depths of the countless pits, there comes a melancholy rustling. Feminism is not dead; the problems have not been put in the past, much less put in the ground. The election of a black (though actually multiracial) president, with its cultural ripples of both approval and reinvigorated bigotry. shows the rustling of race (though actually ethnicity). But the “rush to burial” in these cases often reflects the desire to escape from the burden of past conflicts–and past responsibilities. They suggest that progress is complete, and now we can release ourselves from these areas of cultural conflict, the same way that Will and Grace put an end to homophobia and homohatred…or not. This myth of progress ought to be treated critically, even aesthetically, especially when it seems the case that they arise more out of wishful thinking than a fait accompli.

But, what about the case of postmodernism? Is it wishful thinking that the era of modernism has ended? Certainly, one could argue that we are seeing the end of Modernism as reflected in network-era television. Amanda Lotz has written extensively about the way ‘television’ has changed fundamentally in terms of production practices, financing models, audience measurement, and industrial structure. In many ways, television reflects a notion of modernity through the way it both solves the problem of representation by offering a reconstruction of the world that flows easily between fiction and nonfiction, and turns “traditional” (i.e., pre-modern) culture into an object to be studied, holding out the home for an increasingly perfect understanding of our insides (brain, body, soul) and our outsides (others, space, time).

The postmodern critique sought to blunt this notion of modernism by destabilizing the large scale stories that cultures believed…like the large scale story of progress. But all the postmodern theorizing, once so highly regarded, has dissolved into the radiance of decay. As Alan Kirby wrote in Philosophy Now in 2006,

Just look out into the cultural market-place: buy novels published in the last five years, watch a twenty-first century film, listen to the latest music – above all just sit and watch television for a week – and you will hardly catch a glimpse of postmodernism… The sense of superannuation, of the impotence and the irrelevance of so much Theory among academics, also bears testimony to the passing of postmodernism. The people who produce the cultural material which academics and non-academics read, watch and listen to, have simply given up on postmodernism.1

Kirby argues that postmodernism’s death heralded the arrival of pseudo-modernism, a narcissistic technologized environment where resistance to market forces are seen as futile; the critique of modernist notions of history are no longer ironic and playful, and instead have been replaced by the real desire to return to the stories and toys of childhood. The postmodern sense of ironic interrogation, according to Kirby, is replaced by the trance–a total submersion into one’s own activity. Think of the trance as that space the person next to you goes to when they disengage socially and start texting. Whether this is considered rude or not, it is not the kind of incredulity that marked a postmodern attitude.

But, before we consign postmodernism to the grave prematurely, we might consider an alternative to modernity—what Nicholas Bourriaud2 has called Altermodernity, – the dreamcatcher of the world that is “to-come”:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqHMILrKpDY [/youtube]

Sensing a different way of organization, Bourriaud, a curator and critic, put together an exhibition at the Tate in 2009 that engaged with the aftermath of modernity—as well as the problems with postmodernity—with a different attitude he saw reflected in the work of those contemporary artists who were reworking the new cultural “maze” in order to find new ways of meaning.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=thP5ebKiYAI[/youtube]

He saw these clustered around four different cultural points, which Bourriaud describes as his four prologues:

1. Altermodernity – the end of postmodernism

2. Exile – cultural hybridization

3. Travel – as a new way to produce forms

4. Borders – crossing beyond the current standards of form

The notion of the Altermodern builds off the world as truly multicultural and multivocal–not the residue of the dominance of the West, but a world that is finding new ways to carry on without building in an implicit hierarchy of values.

There is great power in Bourriaud’s vision, and it offers a good way to think about what we are seeing with changes in the forms of ‘television’—changes so complete the term ‘TV’ no longer seems to suffice. These are the changes from networked, centralized hierarchical control, whether through the licensing system of the FCC and the big networks, or the organizational “buffet” doled out by the lords of cable television.

The formal changes include Netflix, Vimeo, Apple TV, YouTube, and other new(er) forms for accessing content. The chain from producers to distributors to exhibitors has fundamentally changed. Correspondingly, the expectations of some viewers have changed, particularly in relation to when and how they enter and participate in the digital environment. Many of the values that are possible in this new world of forms are outlined in Doug Rushkoff’s Program or Be Programmed, values like noting that the connections on the internet are connections between people—not commodities, and that the scale of what we are doing has consequences in our experience of time and space.

Indeed, these new forms have changed the way we use communication cues to interact. In fact, in many of our digital “conversations,” we are losing the visual and non-verbal cues that help make people and their motives understandable. Sherry Turkle3 discusses this, arguing that as we expect more from technology, we expect less from each other. On the other hand, Edward Docx wrote in 2011 in Prospect:

Certainly, the internet is the most postmodern thing on the planet. The immediate consequence in the west seems to have been to breed a generation more interested in social networking than social revolution. But, if we look behind that, we find a secondary reverse effect—a universal yearning for some kind of offline authenticity. We desire to be redeemed from the grossness of our consumption, the sham of our attitudinising, the teeming insecurities on which social networking sites were founded and now feed. We want to become reacquainted with the spellbinding narrative of expertise. If the problem for the postmodernists was that the modernists had been telling them what to do, then the problem for the present generation is the opposite: nobody has been telling us what to do. 4

This, I would argue, is reflected in the new configurations of form in the evolving media ecology. The range of material that can be found on YouTube, but even on Netflix, reflects a growing diversity. To some, the “bar” for entry is lower (i.e., some of the material, even on Netflix, is conventionally “amateurish”). But, this is the cost of the Altermodern. The wider diversity of form is leading to a wider diversity in content. Certainly, there is a lag, especially since the diversity of forms is capable of so much more than the content reaches. Think, for a moment, about the way we could use the hyperlinking of DVD or an online video, combining the ludic unpredictability of a video game with traditional notions of storytelling. At the least, it cold be a new age of Ballyhoo…but, at its best, it could offer new ways to tell stories to each other.

What does it mean to cut the cord? It can mean, “bye-bye, oppressive cable overlords,” getting us out of the position of the “captive audience” that Susan Crawford has recently been describing, where we are victims to the high profit margins of media companies that are too large to suffer competition. (Here she is talking to Bill Moyers on this issue.)

It can also mean cutting the cord to the modern, to the structure that historically recognizes the domination of the Western powers. Part of the notion of the Altermodern thrives on a new understanding of this relationship. If all goes well, if the creativity of form we have experienced is accompanied by a creative explosion in content, perhaps our cynicism can be laid to rest.

My inner Poe, though, sees this happening prematurely.

“In pace requiescat!”

Image Credits:

1. Poe’s “The Premature Burial,” Harry Clarke

2. What have we buried prematurely?

3. Altermodern at London’s Tate Modern

Please feel free to comment.

- Kirby, Alan (2006). “The Death of Postmodernism and Beyond.” Philosophy Now, Issue 58. [↩]

- Bourriaud, Nicholas (2009). Altermodern. London: Tate Publishing. [↩]

- Turkle, Sherry (2012) Alone Together. New York: Basic Books [↩]

- Docx, Edward (2011). “Postmodernism is Dead. What Was It?” Prospect, Issue 185 [↩]