More Dark Nights for DC Comics and Time Warner?

Alisa Perren / Georgia State University

This column takes up where my last column left off in challenging widespread myths about the practices and products of the comics business.1 Only one myth will be called into question this time around, but it is a big one: Marvel and DC Comics have successfully figured out how to transform their comic book properties into profitable multi-media franchises.

This summer’s amazing box office performance of Marvel’s Iron Man and DC Comics-Warner Bros.’ The Dark Knight would seem to underscore how savvy and skillful these two corporate entities have become in exploiting their characters and properties. Yet though these two films have met with astounding success, it remains uncertain whether either company will be able to sustain (in Marvel’s case) or develop (in DC’s) longer-term strategies for turning comic books into motion picture franchises.

Indeed, the next year very well may be one of the defining moments for both companies. Each finds itself in the process of initiating new corporate strategies designed to more fully take advantage of several of their comics. Yet as I indicate below, myriad obstacles remain – obstacles that might prevent us from ever seeing many comic book-based films from reaching motion picture screens (and Netflix queues). Considering some of these obstacles here helps shed light on several assumptions we may have about the operations of the media industries at large, including the monolithic nature of media conglomerates and the impact that individual figures can have within large corporate media structures.

At present, several industry analysts believe the future looks promising for Marvel. As a relatively small company focused on exploiting its own comic book properties for the first time, Marvel has been able to move more quickly in its preliminary efforts to craft a “Marvel Universe.”2 We have witnessed the first steps of this process this summer in both Iron Man and the Incredible Hulk; characters introduced in each of these films made crossover appearances and are expected to appear in upcoming Marvel features as well.

Yet Marvel’s investment of well over $100 million per film also places it in a risky position. So far it has been fortunate to have a mega-hit in Iron Man and a satisfactory performance with The Incredible Hulk.3

However should one of its upcoming projects – which include Thor, Captain America and The Avengers – be received poorly, the company’s future viability could be endangered. All one has to do is consider the immense failure of United Artists’ recent release, Lions For Lambs, and the subsequent troubles faced by this division of MGM in order to see how a single expensive film can play a major part in harming a company.

Given the greater financial protection that a major conglomerate parent can offer, it might seem that Warners/DC have their act together. In fact, much evidence suggests the opposite is the case. Up to now, Warners has predominantly focused on launching (and re-launching) its best-known and most iconic characters, such as Superman and Batman while ignoring second-tier properties such as Green Lantern and The Flash. In spite of efforts to put both Wonder Woman and Justice League films into production, casting and script problems have prevented either from going forth. (The recent writers strike threw another wrench into the development process.)

Beyond the fundamental creative challenges that are typically involved in beginning production on nearly any motion picture, Warners/DC currently faces significant institutional challenges in trying to initiate any comics-to-film adaptations. One key issue involves establishing the precise relationship and chain of command between Warners and DC. Again, on the surface this seems to be a fairly easy thing to do, considering that DC Comics is a part of Warners’ filmed entertainment division as opposed to the publishing arm that houses such magazines as Entertainment Weekly, Time and People.4 Yet though this rather close corporate relationship has been in place for decades, DC’s activities have remained quite marginal to Warner Bros’ bottom line. Further, its newer characters and properties rarely have been mined for feature-length films or television series.

In spite of the array of new comics titles that have come out of DC and its imprints (including Vertigo and Wildstorm) in recent years, Warners has focused primarily on exploiting DC for its most well-known and obvious superhero franchises. (Notable exceptions include the film adaptation of Vertigo’s Hellblazer series, Constantine, and the adaptations of The Road to Perdition and A History of Violence – the latter two coming from DC’s graphic novel arm.) The possible “R&D” function that DC could have served – or might presently offer – has not yet come to fruition, for the most part. Only recently has Warner Bros. appointed a liaison between its motion picture and comic book divisions. Yet rumors seem to indicate that this individual has neither the power in the Warners hierarchy nor the respect of the comic book community.5

Marvel’s recent expansion efforts, along with the consistently strong financial performance of comic book adaptations and related merchandise, have led Warners/DC to begin to discuss their desire to better “use” DC and tap into its rich library of titles. As recently as mid-August, Warners executives promised that announcements were forthcoming about how it would “revamp” its use of its DC properties.6 Yet as one observer snarkily noted, so far all this has amounted to is a “plan to make plans.”7

Meanwhile, DC-based comic book titles that might be turned into movies by other companies are held in a state of permanent limbo. This is the case because Warners (which usually obtains right of first refusal over any comics published through DC divisions) will not produce these projects itself, but neither will it allow the properties to go elsewhere.8 Such contractual stipulations, in turn, make it more difficult for DC to sign top writers and artists to do original work. The net effect of Warner/DC’s mounting contractual demands is that it risks diminishing the quality and types of projects it can acquire and publish (if it has not done so already).

As if rumors about a glacial development process, a lack of a “grand plan” for how to exploit comics across its various divisions, and poor communication between executives in various divisions haven’t caused enough trouble, an ongoing sense of uncertainty looms over many working at Time Warner. The company has struggled ever since its disastrous merger with AOL. New management has decided to streamline the company’s operations, resulting in a continuous shedding of assets and employees. Warner Independent, New Line and Picturehouse all have been recent casualties of this strategy; the CW’s status remains in question as well.

Thus, in spite of the frequent discussions of “big media getting bigger,” Time Warner seems to be going in the opposite direction at present. Of course, this is not to say that Time Warner will cease to exist – rather, its cable divisions and primary motion picture arm are doing quite nicely. But it is to say that this mega-media conglomerate is facing the same rough financial market and uncertain media landscape that everyone else is…and trying to figure out what works.

Where and how DC Comics – along with its rich and largely untapped comic book properties – fit into this rapidly shifting picture is uncertain at this time. Though DC may have been slow to act so far, we shouldn’t necessarily assume this will remain the case in the future. How Marvel fares with its recent proactive efforts at “universe building” as well as its efforts to actively involve comics creators in its feature film development activities might impact how DC (and Warners) proceed.9

Further, the immense critical and commercial success of The Dark Knight could reinforce the value of respecting both original source material and the distinctive voices of those adapting it.

Image Credits

1. Iron Man

2. Incredible Hulk

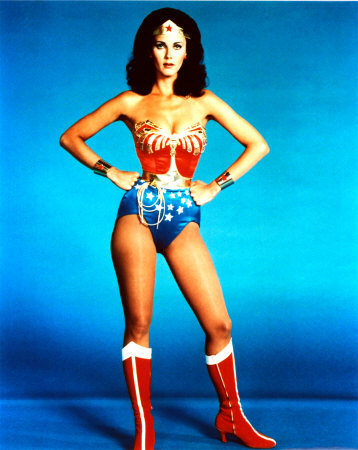

3. Wonder Woman

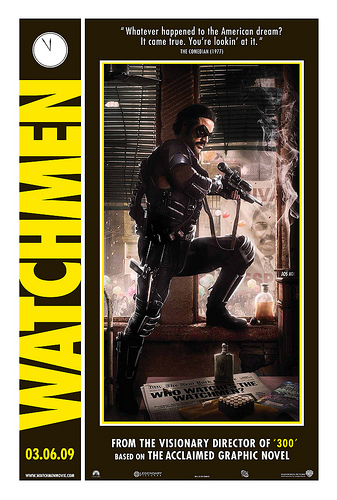

4. Watchmen

5. Batman

6. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

- Thanks once again to Cully Hamner and fellow Gaijin Studios members for their input and guidance with this column. [↩]

- For a discussion of this strategy, see http://weblogs.variety.com/thompsononhollywood/2008/08/marvel-vs-dc.html?query=marvel+vs+dc. [↩]

- The verdict is still out on precisely how successful The Incredible Hulk (2008) was in comparison to The Hulk (2003). Domestically, the newer iteration only made a couple million dollars more than the 2003 version (as of this writing, about $135 million versus $132 million). [↩]

- For a map of Time Warner’s corporate structure see: http://www.timewarner.com/corp/businesses/detail/warner_bros/index.html [↩]

- For a discussion of the current Warners-DC relationship, see http://pwbeat.publishersweekly.com/blog/2008/08/18/dcu-more-important-than-ever-to-the-studio/; http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117990659.html?categoryid=13&cs=1. The comments following the Publishers Weekly article suggest how some fans feel about Warners’ handling of DC. [↩]

- From http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117990659.html?categoryid=13&cs=1. [↩]

- From see http://weblogs.variety.com/thompsononhollywood/2008/08/marvel-vs-dc.html?query=marvel+vs+dc. [↩]

- Sometimes Warners will let creator-owned projects go elsewhere, but in return it demands some type of compensation. [↩]

- For example, Marvel brought in a brain trust of comics creators who have been involved in shaping how the Marvel Comics Universe is presented in the films; see http://www.newsarama.com/film/080711-kevin-feige-interview.html. Also, on Iron Man, they brought in Adi Granov, the comics artist who illustrated Marvel’s Iron Man: Extremis, to work in a design and concept art capacity; see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zk43hVxywHM. [↩]

Nice work on this column…it got me wondering, though, about the distinction between “graphic novel” and “comic” in terms of how each is marketed. I’m particularly interested in two examples that you cite: Road to Perdition and A History of Violence. While these two films were adapted from their sources in (and this matters here) graphic novels, I’m not sure that they were marketed with the original print audience in mind. In other words, Iron Man is a character that we know from the comic book. But Road to Perdition seems to be more of a “property” in the sense of a Ben Hecht play that a fairly limited New York audience might have seen, but the film version eclipsed the original production to the point where the film was far more familiar. People know Spiderman and Batman as iconic characters, with and without film depictions. But how does the less-familiar, “literary” graphic novel as studio property work in terms of acquisition AND marketable product? Is it just an extension of the old practice of mining the genre fiction magazines and New York stage for new material? Or does the association with DC/Marvel make it different?

It will be fascinating to see what happens with The Watchmen especially in terms of a comparison between the iconic comic book superheroes and “literary graphic novels” as film adaptations. Not only will the movie itself be interesting but the critical commentary from both the film and comic book worlds I imagine will be revealing.

There are two issues that I’m particularly interested in… one is about television adapations of comic books. The only hit tv commercial tv show based on a superhero in recent memory is of course, Smallville. What I find so interesting is the natural fit between the comic book format and the television format. While Alisa Perren here talks about the Marvel universe on the big school, what about the DC universe on the small screen? Smallville introduces not only Clark Kent/Superman but also the Flash, Cyborg, Aquaman, Green Arrow and Black Canary and the episodes including members of the Justice League have been some of the most highly rated in the last few seasons of the show and also some of the most narratively and representationally rich.

The other issue which springboards from this is the representational issues and audience reception of comic books. How do audience responses to and readings of comic book/graphic novel texts differ from readings of comic book films and TV shows? To what degree is there concern within the studios about anchoring these texts (and the ability to anchor these texts) in preferred, dominant readings as opposed to more progressive or challenging or subversive readings perhaps offered by audiences and comic book communities?

Alisa,

Have followed your work for a long time. Nice job on summarizing the major conflicts surrounding these two comic book and studio juggernauts. Indeed, I think a lot of the problems Time Warner are having with developing “traditional” DC Comics superheroes to film are caused by the fact that Warner seems continually busy with its own “day to day” studio problems, and having DC locked “in house” per se, perhaps almost makes them take the DC catalogue for granted a lot of the time. While they have, as you’ve mentioned, been struggling to develop other DC properties such as The Flash, Wonder Woman, and Green Lantern (which is buzzed as the next closest to the starting line…for now), they keep coming back to Batman and Superman as their top priorities. While the rebooted Batman franchise has been a phenomenal success, the restored Superman franchise is much more uncertain — Singer’s 2006 Superman Returns is like the big pink elephant in the corner that no one wants to talk about. It deeply divided the fanbase, critics seemed to like it, then later “reconsidered” (even Entertainment Weekly recanted, and they’re owned by Time Warner!), and at the box office and with audiences, it was mildly successful, though it really gained no traction in popular culture, and no noticeable “anticipation” for a sequel — you can still find toys and accessories from the movie in bargain bins in stores worldwide, two years after its release. Warner Bros. seem all but sure to revamp that franchise in the manner they did with Batman Begins — which is probably what they should have done in the first place. It will indeed be curious to see if Marvel’s straight-out-of-the-box success with Iron Man gives Warner/DC the momentum to truly forge new relationships in its corporate hierarchy to make things work in a more tangible, synergistic way. And yes, it’s kind of surprising that a Watchmen film — long seen as one of the most “unadaptable” comic series — has actually been made, considering Warner Bros. can’t seem to get a lot of the rest of its “classic” superhero projects going, or going successfully…

Marvel’s new studio is itself another curious matter. While very successful with Iron Man, their other projects in development seem to be hitting some roadblocks. Though they announced a “group” slate right after Iron Man’s opening weekend, Thor‘s potential director, Matthew Vaughn, is off the project for reasons unknown (he’s also remembered for departing X-Men 3 at the last minute), and is already off directing an “Indie” film adaptation of a very recent Mark Millar comic “Kick Ass.” Captain America — another very difficult project to mount in the current political and cultural climate — doesn’t seem to be any closer to signing a director or star (and the recent “killing off” of the original character in the comic books surely hasn’t made things easier). The Avengers group project that supposedly would corral stars from all the different films, seems rather premature to announce when you only have one other “sure thing” out there (Iron Man). Though Favreau and Downey are well into work on an Iron sequel, The Incredible Hulk seems almost like another belly-flop in terms of critical reception and box office might — it likely cost millions more than Ang Lee’s film, but as you noted, only made around the same amount domestically. Edward Norton was recently interviewed and claimed he hadn’t heard from Marvel whatsoever about either a Hulk sequel, or the Avengers project.

As Mabel noted above, Warner/DC seem to have had more success in television over the past few decades, both in live action and animation — Smallville has indeed been a continual goldmine for Warner Bros., especially in its DVD revenue, and one wonders why they never attempted the seemingly guaranteed synergistic success of adapting the show to the big screen. Marvel’s characters, however, have never really been quite as successful critically or commercially on the small screen, but have lately been dominating the feature film market (though in partnership with other studios). These studios/comic giants are indeed still in the same tug of war they’ve been for decades, only now it’s being played out on the worldwide media canvas, on silver screens and in corporate boardrooms, instead of just in the back-page letters section with fans.

Great piece.

The other indication that there are still major issues with development of these comic properties in other media can be seen in the tumultuous realm of video games. On the surface, this should be an even easier adaptation to make than to film or television because of the perceived audience overlap. Comic-Con is widely attended by all the major video game enthusiast websites (1UP, for example, sent several staff members and dedicated numerous podcast episodes solely to the event). Game publishers used the Con as an extension of the marketing buildup started by E3, often simply transporting their E3 booths to San Diego so that the public could get their hands on recently announced titles. Other events like PAX (Penny Arcade Expo), which is widely considered the “gamer” convention, revolves around the popularity of the most prominent webcomic, with the Penny Arcade guys attending Comic-Con and making room at their own show for booths dedicated to comics.

While this potential for audience overlap would seemingly make the video game world fertile ground for comic properties, both DC and Marvel have struggled immensely to break into the medium. Both Marvel and DC were beat to the MMO punch by City of Heroes, a superhero MMORPG that does not use any commercial properties but allows gamers to develop their own unique superhero. The developer, Cryptic studios, was sued by Marvel for allowing users to create superheros that resembled Marvel characters. Shortly after the suit was settled behind closed doors (without any alterations to City of Heroes), Marvel announced that were partnering with Cryptic make Marvel Universe Online. This would seem to indicate that Marvel realized the logical appeal of creating a licensed MMO that could capitalize on the mainstream success of games like World of Warcraft and were savvy enough to lure in a successful MMO developer that understood comics. However, Marvel Universe Online was cancelled earlier this year and the project reformulated into Champions Online, an MMO using another Marvel property but losing the mass appeal of the most recognizable Marvel characters.

As for DC, the impact of The Dark Knight has caused a surge in Batman based games, but again with problems involving licensing. Apparently EA owns the rights to the Batman movies and is therefore making a Dark Knight game. However, rumors are currently swirling that the game has been cancelled because it missed tie-in release with the film, with others suggesting that it is surging overbudget but will appear alongside the DVD release. However, an entirely separate company, Eidos, owns the rights to the Batman Comics, resulting in Batman: Arkham Asylum, an attempt to capitalize on the Dark Knight but without directly referencing the movie, only the world of Batman comics. Warner Bros. Interactive has published their own game, Lego Batman, which was released a few days ago and meant to appeal to family audiences. On the other end of the spectrum, later this fall will see the release of Mortal Kombat vs. DC Universe, a merging of worlds that has upset diehard fans of both properties, but includes Batman along with a variety of other DC characters. Finally, DC is also prepping DC Universe Online, an MMO announced at Comic-Con that is attempting to do what Marvel tried and failed.

It’s still to be seen how well any of these games will actually do. From April 07 to April 08, only 1 of the top 50 bestselling video games across platforms was based on a comic, and that was the movie tie-in release of Spider Man 3, a game that sold 3.4 million copies but was poorly received by the press. DC seems to have spread their content to far too many publishers to create any sort of consistent brand image or to maintain control over the production cycles of these titles. The big turning point will be to see what happens with MMOs, as a single successful comic-based MMO could establish either DC or Marvel in the gaming world.

Pingback: 10 things concerning Alisa Perren, Greg Steirer & 'The American Comic Book Industry and Hollywood' — DoomRocket