Total Information Awareness – The Media Version

In a recent issue of Flow, Dana Polan observed that “it's been tempting to imagine that Foucault can be enlisted in the analysis of visual culture and media. But one fundamental problem is that Discipline and Punish is about citizens being looked at while television is about them looking:

how to get from one to the other?” Viewed from a slightly different perspective however, commercial broadcasting has, from its inception, been about monitoring viewers. This is why the history of the ratings industry has become entwined with that of military and police surveillance. Various technologies enlisted by ratings researchers, with varying degrees of success, include sonar, thermal imaging, facial recognition technology, GPS tracking and Radio Frequency ID devices (originally used to identify military aircraft at a distance).1

The industry is quick to find ways to exploit new surveillance technologies – a process that includes habituating users to increasingly detailed forms of monitoring, ostensibly in the name of “participation” in the programming process. The comparatively high tolerance of U.S. consumers for commercial surveillance may be in part a result of their long habituation to forms of monitoring associated with the commercial broadcasting system.

If the reach or range of a particular medium can be thought of as a kind of enclosure (virtual or otherwise), some media enclosures have a higher level of feedback than others – a theater, auditorium, or concert hall provides for a greater level of instantaneous response than a TV

newscast or a newspaper, for example. So too does the wireless internet access plan for San Francisco recently announced by Google and Earthlink – although in a unique way. The companies plan to make the entire city a digital enclosure – one within which anyone with a wireless card and a computer can gain access to the internet. In return, Google will use the interactive capacity of the internet to provide users with so-called contextual advertising based on their movements throughout the course of the day. The terms of entry for this privatized digital enclosure include, in other words, submission to detailed forms of monitoring. Google will know when and where you are using its wi-fi service anywhere in its coverage area. If you happen to be using the internet in a city park or cafe, you might receive a targeted ad for a nearby record store (especially, one suspects, if you've been poking around Google looking for music-related information, or writing to someone on Gmail about the concert you saw last week).

The intent of this interactive technology – to gather information about users within the reach of a particular mass medium – is nothing new, despite a recurring tendency to discern in the deployment of interactive media a dramatic break with what came before. Commercial broadcasting, from its inception, relied on the ability to gather information back from the virtual enclosure defined by the medium's reach. Cultural studies of TV have spent a great deal of time and energy thinking about the messages: the programming and advertising with which broadcasters saturate the airwaves. They have spent much less time on what remains of central concern to media producers: the flow of information in the opposite direction. The notion that radio and TV are one-way media has perhaps served to deflect attention away from the fact that in their commercial forms, electronic mass media are characterized by this two-way flow of information: content and advertising moving in one direction and increasingly detailed information about viewer and listener behavior in the other.

The history of commercial broadcasting is, in no small part, the history of the second part of this two-way flow: the ongoing attempt by broadcasters to peer into the homes, offices, automobiles and other spaces reached by their signals. Archibald Crossley, the marketing pioneer credited with coining the term “ratings,” demonstrated early on an innovative streak for gathering information from spaces formerly beyond the reach of commercial surveillance. He won a prize from Harvard, for example, for his pioneering garbage studies, which recruited households to supply him with their household waste, which was then carefully sorted for evidence of consumption patterns. He had realized that the relatively recent (at the time) popularity of brand-name packaging had a double function – not just as a tool for helping producers gain control over national markets but as waste-stream feedback: a rudimentary form of “interactivity.”

Crossley also realized that the success of commercial radio relied upon the two-way flow of information – that listening spaces had to be made interactive in some way. Hence his pairing of radio with a two-way technology – that of the telephone, which he and then C.E. Hooper used to gather information about listeners. Later, of course, radio sets and then TVs were made “interactive” in the sense that they were able to gather and transmit information about how they were used. Various iterations of the Audimeter relied on the mail and then on telephone lines to relay data about listening and viewing habits back to market researchers. Nielsen's People Meters still use telephone lines to transmit television data back to headquarters.

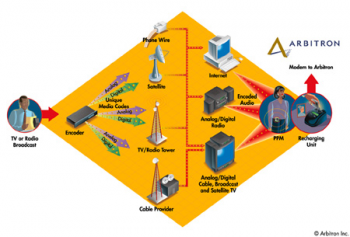

Thanks to recent developments in information technology the monitoring process is going through many of the same changes as content delivery: it is becoming increasingly customized, pervasive, multi-platform and convergent. Symptomatic of this change was an announcement last year by the radio ratings company Arbitron to team up with Nielsen Media Research to develop a multi-media Portable People Meter – a device designed to provide a comprehensive portrait of individual media consumption. The Portable People Meter, or P.P.M, is the ratings industry response to the rise of ubiquitous media – the fact that we are exposed to commercial media (and the ads they contain) virtually everywhere we go. As Arbitron C.E.O. Steve Morris put it, “Media is following you not just when you consciously turn on your satellite radio in your car, or when you consciously flip open your cellphone and get some cable channel delivered to it…It's also coming at you when you walk through Grand Central station. It's on the floor and on the walls…Advertising is becoming incredibly ubiquitous, so you need measurement that is equally ubiquitous” (Gertner, 2005).

The P.P.M. works by detecting embedded audio frequencies, whether in radio songs and commercials or TV shows, which means the wearer has to be close enough to hear the broadcast. Headphone attachments would allow the device to monitor iPod and other portable forms of media consumption. Ratings researchers are also considering ways of integrating P.P.M.s with GPS devices and radio-frequency ID chips. Down the road, the idea is to develop a convergent, multi-media ad-exposure detector that would be able to capture information not just about the music users listen to and the TV they watch, but the billboards they are exposed to throughout the course of their day and even the magazine and newspaper ads they are near enough to see (thanks to RFID chips embedded in the articles and ads). The result would be as comprehensive a portrait of individual advertising exposure as possible – one that included not just a list of which ads were seen, but where, for how long, and at what time of day.

In the near future, the goal is to create a fully monitored media enclosure by matching up this information with consumption behavior, as measured by consumers who scan their purchases at home. When products are equipped with RFID chips, the P.P.M. could double as a consumer meter, gathering information about purchasing behavior as well as advertising exposure. Nielsen calls this merging of viewer and consumer data “fusion” – a futuristic, vaguely utopian moniker for a goal conceived in the early 20th century: the perfection of the scientific management of consumption. Remember Frederick Taylor standing over his workers with a stop-watch, measuring their every move in order to find ways to make them more efficient producers? An all-knowing P.P.M. is the automated equivalent for consumers: a way to stand over them with a stop-watch (and a battery of other data recording devices), measuring their every move and figuring out how it correlates with more effective marketing – that is to say an increase in the speed and volume of consumption.

This is not to say that the emerging regime of total media monitoring is without its stumbling blocks. Nielsen backed out of the Arbitron deal, but has since announced its own consumer total-information-awareness campaign, dubbed “Anytime Anywhere Media Measurement” (or A2/M2). The campaign relies on the willingness of participants to carry monitoring devices with them wherever they go. Stan Seagren, Nielsen's Vice President of Strategic Research, said the company has considered ways of incorporating the device into an item of clothing or jewelry to make it less obtrusive and easier to carry. The cybernetic imagination of marketers at play in the fields of new media even envisions the possibility of a device small enough to be implanted under the skin like an RFID chip, although, as Seagren points out, “our cooperation rates would go down substantially if we started asking people for implants” (Seagen, 2004).

Perhaps the solution will be much simpler: as media consumption goes portable and compact, it's likely that the devices we use to consume media products will become self-monitoring. Cell phones are already being developed that can be used as electronic credit cards, as well as to download, store, view, and listen to media, and to keep track of our

locations. With just a few more tweaks we may find that we're carrying around an all-purpose monitoring tool in our pockets and handbags: the perfection of audience surveillance within a wireless digital enclosure.

1. For a brief and interesting history of the ratings industry's use of technology, see Erik Larson's account in The Naked Consumer: How Our Private Lives Become Public Commodities.

Gertner, Jon (2005). “Our Ratings Ourselves.” The New York Times Magazine, April 10, p. 34, ff.

Larson, Erik (1992) The Naked Consumer: How Our Private Lives Become Public Commodities. New York: Henry Holt and Co

Polan, Dana (2006). “Foucault TV.” Flow 4(7): http://jot.communication.utexas.edu/flow/

Seagren, Stan (2004). Personal interview with the author, Nov. 24.

Image Credits:

1. Mr. Monitor

Please feel free to comment.

more surveillance = more privacy?

This very informative article got me thinking about the possible implications of more comprehensive audience surveillance. Just to throw a couple of ideas out there: more surveillance equals greater fragmentation of audiences. Instead of sitting through advertisements or content that we’re not so wild about, we can have everything tailored to our preferences. The mediasphere w/ imperfect audience surveillance confronted the viewer w/ products and values that he or she wouldn’t seek out and thereby, at the very least, created an image of an alternate viewer/consumer, a fellow member of an imagined public. As audience feedback is perfected, we might see this imagined public replaced by many smaller publics. So in this way, we might become a more “private,” segmented society.

However, once we become accustomed to having our media needs catered to, we might become complacent and overly reliant on a single medium/channel/producer. Why bother to change the channel if all your desires are being met? Producers could take advantage of this complacency by slowly altering the content to meet their own objectives. Many would argue that this is already happening, but it’s easy for me to see how perfected audience surveillance could make things worse.

This speaks to my frustration with the debate over the loss of privacy. The problems seem to arise from the two different ways the word “private” is used. There’s “privacy” as in “not public,” not being confronted with the outside world with its competing desires and values, and then there’s “privacy” as in “not exploitable by corporations and govts w/ data mining software.” The first seems like a bad thing, akin to isolation, while the second seems like a necessary thing, a way of maintaining some autonomy.

So my question is: does everyone accept the fact that perfected feedback cycles lead to audience fragmentation, and that such fragmentation automatically leads to anomie? Are these trends demonstratably true? As I see it, the only way to fight this seems to be to get people to realize the value of being confronted with something they wouldn’t seek out (the value of the public): an uphill battle if there ever was one. It’s interesting to see corporations and local governments join forces to run small-scale experiments with new communications technology. What can we as researchers draw from these experiments?

ineffective labor

Marc, Your article made me think, not about privacy, but about labor, and how, as an economic system, how incredibly ineffective the idea of the total information awareness will be. Think of it: some companies will know how incredibly fragmented, sporadic, and ADD-ish everyone in the digital enclosure is, and do what with it? Yes, we labor to give them the info so a company can sell the info and do what? Make another reality show? Tell the military that potential rebels like pop stars in the park? So I’m mulling outcomes. The US economy becomes so deindustrialized, it has nothing to sell but data with little use-value. We as consumer/workers become economically irrelevant bc we never established any exchange-value for all this info we willingly give up. How’s that for a scenario?