MMO Models: Crowd-Sourcing Economedia

Peter Krapp / UC Irvine

As the game industry seeks revenues beyond sales of shrink-wrapped entertainment software, massively multiplayer online games offer new models—particularly with in-game transactions. This column will compare the approaches of three major players: SONY, Blizzard, and Linden Labs.

Business models for digital culture oscillate between box-office hit and niche product; what models can media studies develop to unfold how this influences both the quality and availability of computer games? Finance draws a distinction between rational expectations that the market naturally finds to a balance: one may realize ‘beta’ in the wisdom of the crowds—and the surmise of reflexive behaviorists that the world is always subject to fluctuating imbalance: one may realize ‘alpha’ in the mass mania of the markets. Media studies is likewise split between those which see crowd-sourcing as a source of progress and transformation, from the printing press to the differentiated scenarios of screen media; and those who warn that the dispersion of our collective attention in the noise of ever larger crowds drowns out everything of value, be it information or entertainment. To mediate between these incompatible positions, this column looks at MMORPG economics, despite the standard disclaimer that in financial history as in media history, the past is no guarantee for the future. Though the insights derived cannot be as formulaic as an alpha or beta deviation, they nonetheless promises some gain for media studies.

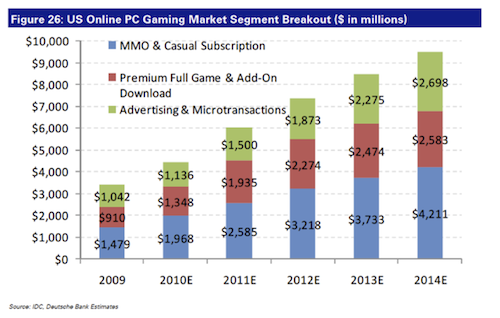

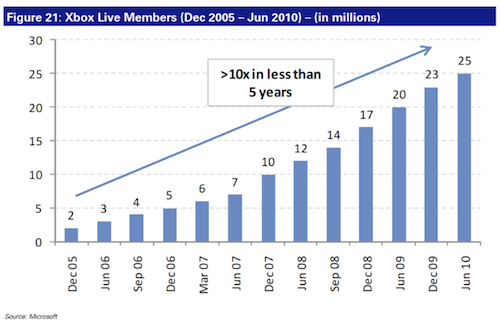

As gaming devices compete with networked home computers, manufacturers like Nintendo, Sony, or Microsoft bet on convergence via Wiiware, Playstation Network, Xbox Live, hoping to reach a broader demographic and additional revenue streams beyond the one-time sale of shrink-wrapped software—through subscriptions, advertising, and secondary markets. Call of Duty Modern Warfare 2 by Activision racked up 1.75 billion minutes of online play in the first six months after publication, and prompted 20 million transactions for additional game content. Since November 2002, Xbox Live has connected more consoles than WiiWare since March 2008 or Playstation Network since May 2006, but the largest number of games is available for the Wii, and Sony has the smallest number of online participants. While both Playstation and Xbox soon granted access to Netflix, Facebook, and Twitter, the Wii added Netflix much later. Beyond subscriptions, game developers have begun to monetize in-game advertising, and some seek to profit from in-game transactions. Industry observers claim that as many as 80% of US Internet users occasionally work or play in synthetic worlds, and estimates for the growth of online entertainment bet on MMOs as a major driver.

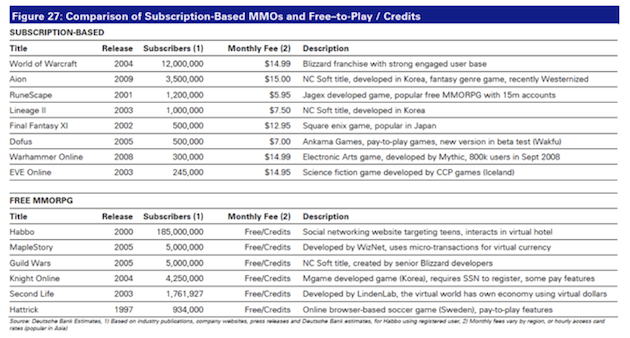

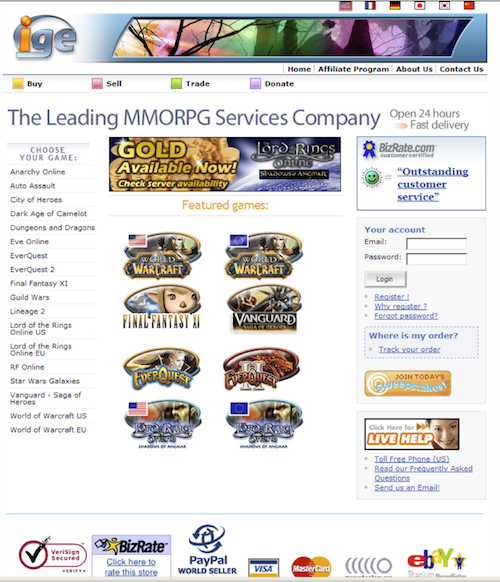

World of Warcraft by Activision-Blizzard claims to have over 10 million subscribers, earning parent company Vivendi about a billion dollars in annual revenue; other online role-play games are often free to play rather than subscription-based, making money through in-game markets instead. Nintendo’s MapleStory for the DS Platform, Final Fantasy and DragonQuest from SquareEnix, and Electronic Arts with Ultima Online and Dark Age of Camelot entered into the competition for synthetic worlds with primary and secondary markets for exchange, barter, and trade. By design, auctions and sales offer money-sinks that delicately balance the time-sink that is online play, with alluring opportunities to earn or win gold or loot or points. The division of labor implicit in role-play creates secondary markets, so it does not surprise us to see virtual swords and elixirs, but also entire characters or player accounts up for trade or sale on eBay, IGE, PlayerAuctions, ItemMania, and other marketplaces. I first encountered these a dozen years ago when a neighbor was promoted from software engineer to usability manager with the task to analyze what drove the sales of an inexpensive alternative to Photoshop—it was used quite a bit by hobbyists to design virtual armor, flags, animals, and other in-game items. Some purists feel the purchase and sale of in-game goods that would otherwise be acquired through play degrades the experience. But other players embrace this new frontier and provide in-game services, trade goods, or start virtual real estate companies. Synthetic worlds allow players different styles – meet someone, explore spaces, solve puzzles, conquer and dominate, spy, heal, cast spells, and so forth. Many game developers count on user-generated content to enrich their synthetic worlds, allowing and even encouraging the creation and exchange of items, skins, and even maps. While some players turn virtual goods into real currency (which is certainly not free of virtuality), others dream of a different life through consumption. Economists like Castronova estimate the entire in-game market might be in the billions of dollars annually.1 Some of that activity might be in sweatshops in China that harness cheap labor to level up characters for paying customers who would pay rather than play for gold or loot, weapons or horses, avatars or entire accounts. But this in itself is nothing new – MUDs in the 1980s had barter and trade, and Ultima Online players were already able to use eBay for virtual goods in the 1990s. There are currently three distinct approaches to this phenomenon among the operators of large synthetic worlds: Blizzard bans such behavior in its World of Warcraft, SONY segregates its Everquest servers, and Linden Labs require some real-money trade of players in Second Life. Here we want to observe transaction costs, and speculate what might happen if these companies espoused a different model in regulating the transfer of social, cultural, and economic values among participants.

Linden Labs provides stable and reliable tools not only for the design of your avatar and its world in Second Life, but also for currency exchange. Its exchange rate fluctuates only minimally, and players enjoy a stable economy, productive play, and a profitable market if they seek to participate in it. However, the terms of use for WoW and its end user license are draconian and clear: real-money trade is taboo, or your account will be banned. What this means for Blizzard is illustrated if we consider some of my students who admitted to as many as eight banned accounts. If we estimate that it takes 15 full days of play to level up to 60 for half of these avatars, 10 days each for level 40 for the other half, one single player paying $15 per month for a year, after an initial cost of $20 each for eight accounts, means more revenue than a participant whose accounts are not banned. Despite interruptions between being banned and signing back up again, this type of player is more lucrative for Blizzard by roughly a third. And are there players who quit WoW because they object to illicit in-game markets? Blizzard has not been able to demonstrate that this is so, even in court, yet asserts that secondary markets undermine their central planning authority, with design limiting risk and play as exploration of the remaining risk. Thus Blizzard pays around 1,300 game-masters $10 dollars per hour to guard against rule-breaking (a popular part-time occupation for my undergraduates), which for WoW means reduced liquidity, an unstable economy, and high regulatory cost.2 Sony Online, in turn, provides two kinds of servers for Everquest, some that permit auctions through the Sony Station Exchange, and some that do not, preserving the sanctity of play for those who feel better that way. When the station exchange was introduced in 2007, an in-game trade volume of $1.87 million produced $274,083 in commissions for Sony, and segmenting the game community reduced Sony’s administrative cost by 30%.3 If we stipulate that demand for real-money trade is similar in both games, the roughly 8.5 million players of WoW in 2007 could have generated a trade volume of $8 million, yielding up to $1.3 million in potential commissions, and a far lower operating cost – paying 390 fewer game masters might have meant saving $8 million that year. The spectrum of these synthetic worlds demonstrates how crowd-sourcing revenues in MMOs poses significant challenges both to rigorous central planning and to playful self-regulation.

Image Credits:

1: Deutsche Bank

2: Microsoft

3: Deutsche Bank

4: IGE

5: Sony Online

Please feel free to comment.

- Edward Castronova, Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press 2005 [↩]

- Nick Ducheneaut & al. (2006). “Building an MMO With Mass Appeal: A Look at Gameplay in World of Warcraft,” Games and Culture 1(4), 281-317. [↩]

- Noah Robischon (2007) “Station Exchange: Year One (White Paper)“, Gamasutra (July 2) [↩]

“Digital purchasing among core gamers has plenty of room to grow,” said Liam Callahan, industry analyst, The NPD Group. “While many core gamers indicate they are purchasing full games and digital add-on content frequently, there are those that stated they have never purchased digital content.”

https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/new-report-from-the-npd-group-focuses-on-core-gaming-and-core-gamers/

This is a lot of data for a short post… Great but I wonder why media scholars don’t correlate sales data with industry scenarios more often, since it is obviously relevant for what we get to see or buy and when and how

@brandonkahler, you may be right that it’s necessary to correlate sales data with industry scenarios, as financial analysts do – but media studies also needs to bring a different perspective, namely how this relates to criticism, to rankings, and to other perceptions and expressions of quality rather than quantity