The Smell of Flak in the Morning: Tropic Thunder’s Talk-Show Tour

Jennifer Fuller / University of Texas – Austin

Tropic Thunder is a comedy adventure film about actors in a Vietnam War movie who are stuck in the jungle after the production closes. According to director Ben Stiller, this movie-within-a-movie premise sets up a satire of actors and movie-making. The most controversial aspect of this film has been the character Kirk Lazarus (Robert Downey, Jr.), a white Australian actor playing a black sergeant, Lincoln Osiris. In Reel Comedy, Downey said about the role, “I trusted that if I was surrounded by the right sense of class and appropriate execution of a comedic adventure, that I probably would not have to wear a flak jacket for the rest of my life.” This article takes a look at discourses that emerged on television this week as the stars promoted the film and tried to stave off ‘flak,’ in this case, charges that the movie is racist.1

As a matter of course, talk show hosts help celebrity guests promote their products. In this case, they were eager to assure the stars and the audience that the movie was not racist. In an interview with Downey, Regis Philbin seemed nervous but was still emphatic as he said, “Some people, I’m telling you right now, may be offended in parts of the movie, but nobody’s out there to hurt other people. It’s just – that’s the way the comedy rolls.” I haven’t seen the movie, so I’m not going to argue whether it’s racist or not; I simply don’t know. Instead, I argue that the bind that Stiller and company find themselves in – making this movie and then convincing people (read: black people) that it’s not at all racist, is indicative of the contradictions in our supposedly ‘colorblind,’ hipster ‘post-race’ present. To ‘get it,’ we have to know the political potency of blackface , but not be so invested in it that we find blackface decidedly unfunny.

And I want to be very clear about this: Robert Downey, Jr. is in blackface. People have quibbled with this term, I suspect because it would tie his performance to an ugly, unredeemable history. (That is soooo not ‘post-race.’) These online posters say Downey is not in blackface because his makeup and his performance are very ‘realistic.’ This astonishing defense reflects a shallow understanding of how blackface performance was regarded as ‘realistic’ in many ways, no matter how ridiculous it may look and sound to us now. Blackface performers were praised for approximating the audience’s notion of ‘real’ blackness. In blackface, the transformation from whiteness to blackness was fascinating: sheet music, posters, publicity photos and films often showed performers ‘normal’ and ‘blackened up.’ The thrill and perceived realism of their performance was bound up with the knowledge that they were indeed whites playing blacks. Praise for Downey’s ability to “fool” us is by no means the opposite of blackface performance. To be clear, by saying that Downey is in blackface, I’m not saying that the film or the role are necessarily racist. But he is definitely in blackface, and several interviews this week respond to his role as such. For example, on the talk shows, viewers were invited to revel in Downey’s transformation – in split screen in the case of Live with Regis and Kelly. Whenever stars are in film roles that require significant physical transformation, that transformation – weight loss or gain, heavy makeup and so on – is discussed. But this is expressly about racial difference, and that is no small variable.

Stars and hosts discussed Downey’s ability to “become” a black man (always “Osiris,” not “Lazarus”) beyond his onscreen performance. Several interviews with cast members said that Downey stayed in character all the time on the set, and that he improvised many of his lines. While this was presented as evidence of his commitment to the role, it creates a troubling image of Downey extemporaneously ‘acting black’ outside of supposedly carefully crafted, politically-savvy dialogue. Regis’ daughter and co-host for the day said that after shooting, Downey would call his wife while he was still in character. To hoots from the audience, Downey said, “She thought it was sexy.” Downey followed this with a story about how (likely white) female members of the crew were attracted to him when he was “Osiris,” but otherwise, not.

On BET’s teen variety show 106 and Park, co-star Brandon T. Jackson, often described as “the real black guy” in the Tropic Thunder cast, talked about Downey staying in character in ways that I want to believe are facetious. Jackson, who is a comedian, said “[Downey] would stay black. Ben Stiller would yell ‘Cut!’ and he’d be like, ‘Let me go back to my trailer, get some barbecued chicken and listen to Kanye West CDs! I’m like, this dude is really black, what is this?” Jackson told this story in a joking manner, but it wasn’t well-received. One co-host’s mouth swung open, and the other yelled “ooooh!” and smiled tightly. The audience was mostly silent except for a few groans and giggles. This and other statements undercut what was clearly his purpose for being on the show – to ensure black viewers that Tropic Thunder is not racist. 2

BET and DreamWorks – the studio for Tropic Thunder – are both owned by Viacom.3 Tropic Thunder’s white leads (Stiller, Downey and Black) were on 106 and Park two days later in an appearance that was visibly uncomfortable and for the most part, painfully unfunny. The highlight was when the hosts pit Stiller and Black against each other in a dancing ‘battle.’ Their terrible dancing invited mockery and laughter (at them, not with them) from the audience and the hosts.4 It was the only part of the show where the studio audience seemed to be genuinely enjoying the cast’s visit. Personally, I wasn’t interested in mocking their dancing – I could barely watch, I was so embarrassed for them. But it was the only time during this press tour that I saw the cast as actually taking a risk. Their whiteness was hypervisible here, not as the embodiment of media power, but as awkward, outnumbered and ‘looked at.’

In one interview, Downey wondered why Stiller offered him an acting opportunity that was so risky. I have a similar question – why would a white filmmaker take on such a loaded image as blackface? Black performers have grappled with it as a way to challenge the racist constraints on their lives and art, but Stiller has no such burden. I suspect that the need to bring back blackface (against all good sense), much like today’s feverish white desire for the right to say “nigger” (again, against all good sense) is yet another way to grapple with a crisis in white identity. This crisis is produced by the contradictions of a moment in which whiteness is visible and criticized (like Stiller and Black writhing on BET) and yet still incredibly powerful (certainly like Stiller, and perhaps like Black).5

Some support for this thesis can be found in the flow of the two programs from August 14. The segment immediately preceding Downey’s GMA interview was a story about the “new face of heroin addiction,” which the story depicted as “suburban teenagers.” The segment focused on the stories of two white middle-class girls, but it never said what the old “face of heroin” was (black, brown, and poor). The story ends and Diane Sawyer announces that Downey’s interview will be next. This segue unintentionally invokes heroin’s “old face” in terms of Downey’s history of drug addiction, and in terms of his character’s blackness and the fact that he is a soldier in the Vietnam War (where heroin use was widespread). Two talk shows that included interviews with Tropic Thunder cast members also covered a recent report on when whites will become less than half of the U.S. population. On CBS’ The Early Show, this report was covered within the first ten minutes of the broadcast. On GMA, it was consigned to the news ticker. As Downey talked about the difficulty of being in stage makeup, we cut to images of him getting his skin darkened. And on the bottom of the screen, viewers could read the following, in all capital letters: “Brookings survey predicts that Americans with white, European roots will be minority by 2042. Hispanics, Asians and Blacks will become majority.” These reports about white purity and dominance under siege (blackening?) make for a decidedly unfunny subplot of the Tropic Thunder press tour.

Was the press tour successful? Perhaps. Tropic Thunder is a success at the box office, and has avoided a noticable amount of flak about its racial politics.6 Reviews of the film regard its racial politics as either successfully satirical or a ‘non-issue.’ And that’s a relief, isn’t it?

Image Credits:

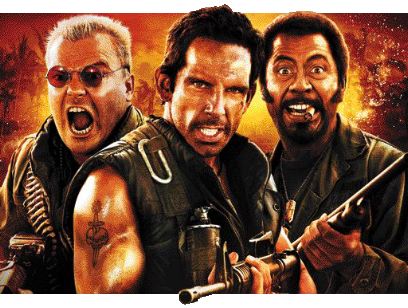

1. Tropic Thunder

2. Robert Downey JR. in Makeup – Photo by Jennifer Fuller

3. Ben Stiller on 106th and Park – Photo by Jennifer Fuller

4. Jack Black dancing on 106th and Park – Photo by Jennifer Fuller

5. Downey mimicking Stiller on 106th and Park – Photo by Jennifer Fuller

6. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

- This article is based on viewing cast visits to CBS’s The Early Show (2 episodes), ABC’s Good Morning America (2 episodes), syndicated show Live with Regis and Kelly (2 episodes), BET’s 106 and Park (2 episodes), Comedy Central’s The Daily Show, and an installment of Comedy Central’s Reel Comedy which included behind-the-scenes interviews with the cast. [↩]

- Immediately following these comments, Jackson gave repeated assurances that the film was not offensive. Elsewhere, Stiller and Downey said that Jackson helped to keep the film’s racial content ‘accurate’ and inoffensive. [↩]

- Since June, DreamWorks has been splitting from Viacom. Ownership of recent properties such as Tropic Thunder isn’t yet clear. Viacom owns Comedy Central, as well. [↩]

- Black turned his dancing into a comedic routine that was favored over Stiller’s earnest performance. Downey did not dance, which is in accordance with the fact that he is not a comedic performer. But he did judge the battle, which raises interesting questions about his honorary ‘blackness’ in this moment. [↩]

- Many scholars have talked about this crisis. For example, see Bill Yousman, “Blackophilia and Blackophobia: White Youth, the Consumption of Rap Music, and White Supremacy,” Communication Theory 13 (4), 366-391. [↩]

- Tommy Shriver, chairperson of the Special Olympics, led a protest against the film’s use of the word “retard” and its depiction of mental disability. [↩]

Great article, Jennifer! You bring up some really interesting points — particularly regarding the taking on of blackface by a white actor and white director as an example of their crisis with white identity. Undoubtedly, you are on to something when you look at the ways in which Downey’s star persona and personal history with drugs informs the reading of his character in Tropic Thunder. Thank you for tackling this movie and its publicity!

Great article, Jennifer! Though I’ve yet to see the talk show appearances you speak of, I can imagine the level of discomfort that must be palpable in discussions about Downie’s performance. I also love your analysis of flow, which nicely contextualizes the interviews and again, reveals the possible implications of black face in Tropic Thunder.

While you did not tackle the text itself (which is a perfectly valid and perhaps more productive approach in this case), I think that the film would support your conclusions about black face as a response to a crisis of whiteness. I won’t say much more, as I do not want to spoil the film for those who have yet to see it, but I definitely feel that issues of authenticity and performance are self-consciously explored in the film, raising many of the same concerns you bring up here.

I’m always uncomfortable with the desire to conduct political evaluations of comedy-as-text, and I think the article’s attention to the discourses in the film’s PR effort is really productive. As a British reader I don’t have direct access to the show’s mentioned and my reading of the film itself was that it was a spoof of actorly blackface (eg. Olivier in Othello), though this is not very coherent with an action spoof, so I was perhaps being too generous. Your examples seem to back this up.

As an aside, and OT, something that has interested me in regards to comedy and blackness (specifically African-American film comedians) is the recurring habit of putting comedy actors into some kind of drag. Its not exactly an avalanche of films: essentially Eddie Murphy (Nutty Professor and sequel, Life), Martin Lawrence (Life and Big Momma’s House) and the Wayans (White Chicks and Little Man)… But it strikes me as an odd use of a physical spectacle sustained throughout a narrative, and the only comparison I can see with a white comedian is Robin Williams in Mrs Doubtfire.

Great article, it raises some interesting points, specially about the crisis in whiteness identity and the inseparability of a movie and its political context. Still, I do not think that the movie was a racist movie. In fact, I think this movie in fact confronts Hollywood’s racism, racial politics and typecasting practices.

I also do not think that the Alpa Chino character was put there as a ploy to avert racism accusations, but as a way to confront the typecast hollywood representations of black men (Downey’s character) with an alternative representation of an intelligent, artistically successful, sophisticated black man who in fact finds the other representation offensive (Brandon T. Jackson’s character).

One last point, I noticed that Downey’s Australian character (Lazarus) looked remarkably like Mel Gibson’s Martin Riggs in the Lethal Weapon saga, both in physical appearance and facial expressions (the blue dilated pupil contact lenses did their job right). Perhaps Tropic Thunder was poking fun at Lethal Weapon’s (i think quite stereotypical) portrayal of the black sidekick (Danny Glover) and the white hero (Mel Gibson)?

The box office hit, Tropic Thunder, is under question about its racial references. Robert Downey Jr. plays a black army sergeant names Osiris. This white actor from Australia dawns on blackface, which references the theatrical makeup that was part of racist, stereotype performances of the past. It started off with white actors blackening their face with greasepaint or shoe polish, and they also accentuated their lips to make them big and full. It was seen as exploitation of the African American culture; “Blackface performers were praised for approximating the audience’s notion of ‘real’ blackness” (Fuller). This is why it was a little questionable that they had Downey Jr. do this for the movie. It may have been for humor, but the history that it represents is very racy. But even off stage, Downey Jr. took his makeup and character a little too far. After the camera would stop rolling, Downey Jr. would still try to “stay in character” by saying things like, “Let me go back to my trailer, get some barbecued chicken and listen to Kanye West CDs!” (Fuller). By a statement like this, he is feeding into the stereotype of black people’s “love for fried chicken” and hip-hop music.

In Darnell Hunt’s article, “Making Sense of Blackness” in the reader, he discusses the show Amos ‘n’ Andy, which turned into a television show using blackface actors. The NAACP worked on “eradicating media images of black Americans that seemed to work against the movement for racial integration in America” (148). “The NAACP eventually succeeded in its campaign against Amos ‘n’ Andy” (148). But, it is roles in movies such as Robert Downey Jr.’s that help to remind us of a time when parts such as this were racial and used for mockery. In a way, Downey Jr.’s character helps to repeal the work that the NAACP was dedicated towards.

Jack Black and Ben Stiller, the other leading roles in Tropic Thunder, went on BET’s (Black Entertainment Television) 106 and Park as guest stars. They were asked to perform a dance battle where “Their terrible dancing invited mockery and laughter (at them, not with them) from the audience and the hosts” (Fuller). This feeds into the stereotype about how white people cannot dance. 106 and Park is considered by many as a “black show” where, by the pictures of the Tropic Thunder cast members on the show in the article, the entire cast was African American. The white guest stars were seen as “uncool” and bad dancers. In Jhally and Lewis’ article, “White Responses,” in reference to another “black show,” The Cosby Show, someone said that, “it was more ‘fun’ and ‘colorful’ because it was a black show” (161). One can parallel this to BET’s 106 and Park. The fact that the white actors were laughed at and made fun of shows how they were not fun and “cool.” Once again, there is a clear distinction here between the races. Usually, “To be ‘normal’ here means, as we have seen, to be part of the dominant culture, which is white” (160). But here, the Caucasian actors are the abnormal ones; the tables have been turned on this television show.

The character that Downey was portraying was at its core mocking actors. Though I understand the reaction to him donning “black face” you have to remember that the role is satirizing a high-maintenance white actor’s portayal of a black man. In effect, this is mocking actors and even, if you want to take it that far, white people. The fact that it was purposely done in a way that mocked stereotypical black “token” roles in film was a statement that this was an arrogant, out-of-touch actor (the Australian actor Downey was playing within the role) who, in his ill-conceived belief of his own self-importance as an actor didn’t even realize he was being offensive. Look deeper people. When we can see the concept behind the superficial costume of the role and what it’s really saying we’re much close to understanding.