George Carlin, the Last of the Trinity

Bambi Haggins / University of Michigan

It was well after midnight on June 24th when I read that George Carlin had died. It seemed oddly appropriate that I would hear about the legendary comic’s demise in the early AM—that had been, after all, when I had first gotten to know him. Although I remember watching him during prime time with the family on The Ed Sullivan Show doing an early version of the “hippie dippy” mailman and, later, on The Flip Wilson Show, the Carlin to which I was uninitiated had been inaccessible to me. Late at night in the summer of ’75, my curiosity having been piqued by a lively “discussion” between parent and sibling, I sneaked my sister’s Class Clown out of her room. Curled up in the den with the then futuristic white space helmet shaped eight-track player, I listened (very carefully) to the “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” for the first time.1 The sound, the timbre, the timing and the semi-salaciousness of the routine were hilarious and intoxicating in a way that was quite different from our nap time audio treats of Bill Cosby’s Wonderfulness:

“There are no bad words. Bad thoughts. Bad Intentions. …you know the seven don’t you? Shit, Piss, Fuck, Cunt, Cocksucker, Motherfucker, and Tits, huh? … Those are the ones that will infect your soul, curve your spine and keep the country from winning the war.”

Using language-in all of its vernacular glory, Carlin and his revolutionary comic brethren—Richard Pryor and predecessor Lenny Bruce—reflected the zeitgeist of an era from different social quadrants and personalized comic pedagogies.

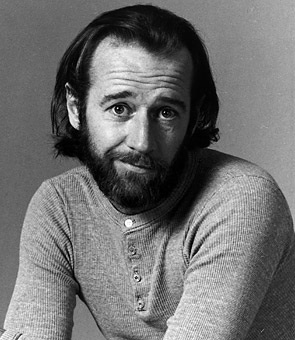

“I changed with the country then, and I got back in touch with my outlaw rebel self. I was 30 years old in 1967, the Summer of Love, and the people I was entertaining in these mainstream nightclubs were 40 years old and hated their 20-year-old kids, who were burning down their schools,” said Carlin. “I gravitated toward the 20-year-olds, and that’s when my comedy changed.”2 In 1970, he traded his clean-cut image and material for the uniform of the counterculture (beard, long hair, jeans) and an act that reflected the times, which did not go over well on the Vegas strip. After being released from a three year contract at the Frontier Hotel, Carlin created an act, unencumbered by the prohibitions of the “main room,” that presented conventional wisdom for youth culture (anti-establishment, anti-war, pro-drug and pro-sexual freedom).

By 1975, Carlin had found the voice and the persona that would make him a comic icon for decades to come. Carlin’s material fell within three broad categories, two of which the comic would later refer to as “the big world” (disagreements on politics, religion, race, consumerism, war) and “the little world” (universal experiences that we all know, physical as well as emotional: the prototype for observational humor). The final category was, of course, language—not just by challenging the notion of “bad” words, but also by continuing to make audiences think about the power and preposterousness encompassed in our ongoing struggle with making meaning through words. As Mel Watkins and Bruce Webber note, “By the mid-’70s, like his comic predecessor Lenny Bruce and the fast-rising Richard Pryor, Mr. Carlin had emerged as a cultural renegade.”3

When I watched the first episode of Saturday Night Live in the fall of 1975 at the house of a fellow staffer on our high school newspaper (in the basement, of course), it marked the second of my many late night encounters with Carlin. The fact that Carlin was hosting supplied coolness cred for the show for this (moderately geeky) pubescent crowd (and especially for the dorky frosh that I was). The peals of over-determined laughter at Carlin’s hippie dippy weatherman, Al Sleet’s “faded” forecast (“Tonight: Dark. Continued mostly dark tonight, turning to widely scattered light in the morning”) proved his countercultural cred.

While the cultural and linguistic referencing seemed hipper and more clever at the time, it, nevertheless, solidified my belief that the “best” comedy is more than simply joke, setup, joke.4 Due in no small part to HBO Comedy—my greatest joy as a premium cable premium cable adult for the past 15 years—I have watched hours of stand-up in the pre-dawn hours: Carlin, Pryor, and Robert Klein, as well as their comic progeny: Eddie Murphy, Chris Rock, Margaret Cho, Dave Chappelle, Wanda Sykes and Lewis Black.

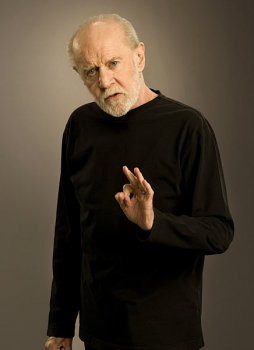

My most recent viewing date with Carlin was a two-night stand; HBO aired 11 of comic’s 14 specials-beginning with On Location: George Carlin at USC (1977), and ending with George Carlin: It’s For Ya (2008). Arguably, all of Carlin’s routines can be read as treatises on hypocrisy and absurdity of changing cultural and social winds as well as reflections on the human condition, for better and for worse. However, from the disclaimer of journalist Shana Alexander, which lauded Carlin as “one of the generation’s philosophers of comedy” and the sensibilities of individual viewers for understanding their power to choose, I was reminded of how cutting edge his 1977 special was both in terms of style and content. In this iteration, the comic was still in the process of crafting an act that made audiences laugh and think without catering to them (learning to deal with “the silences”).5 By the time I watched It’s Bad For Ya, in the wee hours of the next morning, I marveled at how the comic seemed different and, yet, unchanged. In his New York Times piece the day after Carlin’s death, Charles McGrath aptly described the sense and sensibility of the comic:

“…[Carlin] had a gift for saying-and thinking-things that other people wouldn’t or couldn’t. He wasn’t as threatening as Bruce or Pryor. [In his later years]… his persona was warmer, cranky rather than angry. But his humor was always a little subversive and aimed at puncturing hypocrisy and feel-goodism. …Though he delivered it with a smile, his forecast was the same as Al Sleet’s: dark and getting darker.”6

In a different context, I could analyze in detail the power of Carlin’s comic social discourse, further contrast it with Pryor and detail how it reflects and refracts American popular consciousness over the past four decades. Instead, I have chosen to offer the reflections of a fan of Carlin and standup comedy, in general.

What I most revere about Carlin is his ability to make you laugh at (and consider) things with which you might disagree. I believe in some iteration of what Carlin refers to as an “invisible guy in the sky” (AKA God), but I still appreciate his scathing critique of organized religion (the institutions that tell folks that the “all powerful, all-knowing” being “needs your money”). My closest sister, whose eight-track I borrowed, could fit Carlin’s definition of the “child worshipping,” “professional parent,” who endeavors to schedule meaningful activities for her kids; I don’t quite see how soccer and science camp is cheating them out of a childhood. And, finally, despite my wholehearted agreement that there are questionable subjects of adoration and inspiration (based on, among other things, success in sports), I am not ready to concur with the “Fuck Lance Armstrong” sentiment that began Carlin’s final special. It did, however, make me laugh my head off.

If indeed we are given a “ticket to the freak show” when we’re born (“a front row seat if you’re born in America”), having someone as gifted as Carlin to give both the color and the play by play for the pageant is both a gift and a necessity. His loss will be felt on both sides of the footlights. Jon Stewart referred to Carlin, Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor as the “holy trinity of comedy.”7 Now the last of the trinity is gone. Who will become the new philosophers of comedy, and who, with candor, irreverence and wit, use comic discourse to make us ask, “WTF?”

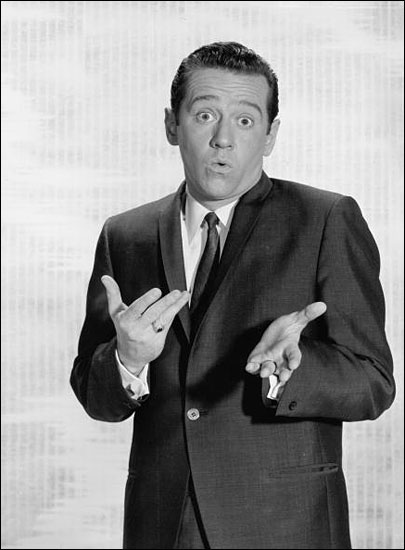

Image Credits:

1. Carlin during his squeaky clean early years (1965).

Please feel free to comment.

- I was a senior in high school before i realized that i had listened to the wrong cut. It was “Filthy Words” from Occupation: Foole (1977) that began the judicial odyssey. See the “70s” timeline at Carlin’s official website [↩]

- Sarko, Anita. “George Carlin,” Interview, November 2007: 37. [↩]

- Watkins, Mel And Weber, Bruce. “George Carlin, Comic Who Chafed At Society And Its Constraints, Dies At 71,” New York Times. New York, N.Y.: 24 June 2008: C.12. [↩]

- I recount the process of watching the “word association” sketch on Saturday Night Live in December of 1975 in that same basement and the kinds of laughter generated by the same of teens upon seeing the now famous Richard Pryor and Chevy Chase exchange at the beginning of the first chapter of Laughing Mad (Rutgers University Press, 2007). [↩]

- This Was Also Underscored By The Freeze Frame Intertext Warning Viewers That The Real “Blue” Material (“Filthy Words”) Was Coming Next. [↩]

- McGrath, Charles, “A Master Of Words, Including Some You Can’t Use In A Headline,” New York Times, June 24, 2008: E1 [↩]

- Stewart coined this phrase in Carlin’s introduction at George Carlin: 40 Years of Comedy, taped and aired from Wheeler Theater, Aspen, Colorado, as part of Aspen Comedy Arts Festival in February 1997. It aired on HBO as Carlin’s tenth HBO special. [↩]

Pingback: “Age” by Larry Miller « scanned thoughts