Looking at Rock Stars

Thomas Swiss / University of Minnesota

If we had to write our academic pieces as if they were poems, as if every word counted, how would we write differently? How much would we write at all?

—John Law, co-developer, Actor-Network Theory

In the collecting world, photographs are big business. Setting new records, Andreas Gursky’s Rhein II sold for $4,338,500 at Christie’s in 2011; Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #96 was auctioned for $3,890,500. By these lights, selling rock-related photos is a small (but growing) business. A limited edition double-portrait of Grace Slick and Janice Joplin from a magazine photo shoot in 1967 costs $6,500 at the online site Wolfgang’s Vault. Jimi Hendrix burning his guitar onstage at the Monterey Pop Festival that same year (“print #48 of 50”) will set you back $10,000; a rock portrait by photographer Annie Liebovitz, sold elsewhere, can cost $50,000 or more. In the last few years, record companies like Sony and others have also realized that images of their artists, buried in their archives and mostly used for boxed sets, are sources of new revenue as music sales continue to decline.

Collected in coffee-table books, sold in galleries and online sites, featured in special issues of Q, Spin, Rolling Stone, and other magazines – venues where the photos often first appeared — rock portraits play an important role in creating the celebrity culture of pop music. Among other things, they reinforce and amplify the “personalities” we imagine making the recordings and giving the performances that constitute a rock musician’s principle body of work. Some may also embody particular artistic designs, demonstrating how aesthetic form brings together musical and social content in and through the image.

It’s hard thinking about portraits, even those by great photographers, as art and not in terms of the “essence” of the person pictured. Here is well-known rock photographer Jim Marshall on his work: “When I’m able to capture the essence of my subject and show something of what they do or reveal who this person is, then I’ve achieved what I want to do.” But whatever the mimetic quality of the portrait — Marshall’s or anybody’s — the photograph remains, of course, a representation of the subject, one whose value as an approximation is less determined by its descriptive character than by the coincidence of the perceptions shared by the photographer and the viewer. Said another way, the “value” of rock portraits in large part reflects both the social and topical knowledge of viewers.

One kind of knowledge I want to think about here – a topic explored by art critic David Lubin in his intriguing book on JFK — is the knowledge of other images.1 After all, some rock portraits look like or invoke a range of previous images that have already staked a claim on our cultural imagination; others draw on generic or well-known artistic conventions. And while other rock photographs work in other ways, all photographs that are widely valued draw on and add to the prevalent discourses and stories about music and musicians already in play in culture. But how do we tell and talk about these stories? And how do we talk about the photographs themselves? Thinking about these two questions leads me to think about writing itself. And John Law’s questions, both the one in the epigraph above, and this one: How might we imagine an academic way of writing that concerns itself with the creativity of writing?

The creativity of writing. Columns on Flow are meant to be speculative; my last column talked about working collaboratively to escape the tyranny of genres in creative fields. This column will focus in its own way on genres; in this case, on mixing genres as a way of doing criticism. It experiments with the form of the short essay, and unlike most writing on Flow, it does not proceed in traditionally linear fashion and does not make an explicit argument. Instead, it engages the contingent, the associative, and the inter-textual by linking some images and a dozen excerpts from a handful books, blogs, and articles. Among my tutor texts for this approach are John Law’s book, After Method: Mess in Social Science Research2; David M. Lubin’s Shooting Kennedy3; Robert Ray’s The Avant-Garde Finds Andy Hardy4 ; writers, like Roland Barthes, who deploy fragments with cumulative intellectual and aesthetic surprises; and, of course, contemporary texts composed through the practices of remixing.

Over the last few decades, interdisciplinary methods and an understanding of methods as poetics or interventions have become increasingly visible in many fields. In contrast to traditional approaches, some make use of techniques learned from games, the automatism of digital technologies (especially cut-and-paste) and so on, as alternative modes for the production of knowledge. My own approach here is to create an assemblage (more like the art world’s notion of assemblage than Gilles Deleuze’s conception) that is a gathering of found materials fit together not to make a specific argument but rather to serve as an alternative heuristic. An assemblage is not a fixed arrangement; it’s an open-ended, uncertain process. Assemblages are objects (like this ‘‘finished’’ column), but they are also activities.

In some venues, remixing as a form of composing inhabits a contested terrain of intellectual property and can be marked by ethical (‘‘intellectual dishonesty’’) and legal (‘‘plagiarism’’) issues; regardless, remixes, like other interventions in academic research methods, are generally seen as ‘‘experiments.’’ I offer the following assemblage in that spirit. In what follows, and in a forthcoming column, individual fragments from others’ texts are overlapping and iterative while the structure of the whole attempts to pay attention to unintended effects. In addition to the influences I have mentioned, my experiences as a poet working with fragments, resonance, ambiguity, and alternative forms and formats generally influenced this present experiment.

All comments from Flow readers are very much welcome as I think my way into this experiment.

An Assemblage of Photographic Portraits and Texts

Public Weeping

The Old Testament is replete with references to weeping. The ancient Hebrews wept as part of their supplications to God and before going to battle. The Gospel writers did not feel that tears were a threat to either the manhood or godhood of Christ and dutifully recorded that “Jesus wept.” Perhaps drawing inspiration from this emotional display, early church thinkers considered tears a gift and a natural accompaniment to spiritual, even transcendent, experiences. The great theologian Thomas Aquinas, like the ancient Greeks, made the distinction between the very public weeping that had characterized Hebraic culture, and the idea that it was frequently best to cry away from people’s prying eyes.5

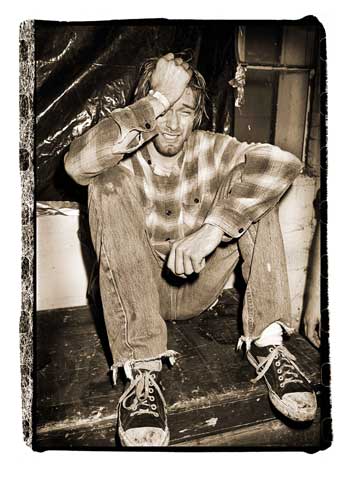

Stars Want to Control

Nirvana did a brilliant gig, I got great pics of him smashing the guitar and then he went backstage and burst into tears. I thought it would make a good photo, but should I take it because it is a vulnerable moment? I am not a paparazzi, I am a documentary photographer. He knew I wasn’t pushy and I took a shot — he didn’t say no. I took three in all and the third shot he was crying, in the second shot he was sort of ok and the third one he was smiling. A minute between the three was about all this different kind of energy inside him and when he came backstage the energy had to go somewhere. Normally rock stars want to control how they look to the public.6

A Gallery of Poses

The history of portraiture is a gallery of poses, an array of types and styles that codifies the assumptions, biases, and aspirations of the society.7

As Time Goes By

As time goes by, and images pile, one upon the other, in the imaginations and fantasies of viewers, coalescing into a visual narrative, they demand to be remembered. Through this remembering, they become real and believed, and this believing informs ever new and imaginative ways of seeing.

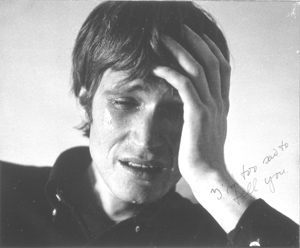

I’m Too Sad To Tell You

Bas Jan Ader’s most popular work is his 1970 silent short film piece, I’m too sad to tell you, that consists of the artist crying in front of a camera after a brief title. The interests and concerns in Ader’s oeuvre locate him in similar art historical tropes of conceptual and performance artists of the 1970s, such as Chris Burden and Bruce Nauman.8

Whatever Caused the Tears to Flow

The artist is crying and too sad to tell anyone why. Whatever caused the tears to flow (the artist never publicly stated the reason) is ultimately beside the point. And yet Ader reenacted his private sadness, restaged it, photographed it to mail to others. While his piece retains a “real” sadness, it keeps vital the artifice and melodrama inherent in placing himself before his own camera while crying. Almost all of Ader’s work pulsates with a crisis of some personal intensity. His sincerity is sincere – until it’s not only sincere.9

The Phallus Can Only Play Its Role As Veiled.

–Jacques Lacan

Just Love Him So Much More For That!

Yes, I do love to see a man cry. I don’t think this is a weakness. I think it is a strength. My hubby has cried a few times over the years. Tears of grief, tears of pain for others, tears of joy. Just love him so much more for that!10

Image as Witness

Barthes (1984) draws our attention to the fleeting nature of the moment captured in the photograph and the extent to which contemporary experience, along with limited knowledge of the specific context within which – and purpose for which – the photograph was taken, inform ways of seeing and introduce slippages of meaning into any view of the image as witness.11

For me, the value of [the] image is not its verifiability, but its incitement to wonder.

–Lawrence Weschler12

Image Credits:

1. 100 Greatest Rock ‘n Roll Photographs

2. Kurt Cobain in a vulnerable moment

3. Bas Jan Ader

- Lubin, David M. Shooting Kennedy: JFK and the Culture of Images. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. [

]

- Law, John. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. London:

Routledge, 2004. []

- Lubin, Shooting Kennedy [

]

- Ray, Robert B. The Avant-Garde Finds Andy Hardy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995. [

]

- http://artofmanliness.com/2008/06/19/when-is-it-okay-for-a-man-to-cry/ [

]

- http://www.iantilton.net/nirvana_new.html [

]

- Brilliant, Richard. Portraiture. London: Reaktion Books, 2004. [

]

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bas_Jan_Ader [

]

- http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_7_37/ai_54169956/ [

]

- http://askville.amazon.com/love-man-cry/AnswerViewer.do?requestId=16817264 [

]

- Van Leeuwen, Theo and Carey Jewitt. Handbook of Visual Analysis. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2001. [

]

- Weschler, Lawrence. Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences. San Francisco: McSweeney’s, 2006. [

]

Pingback: Looking at Rock Stars Thomas Swiss / University of Minnesota and John Barner / University of Georgia | Flow