The Great Wikipedia Blackout, The Stop Online Piracy Act, and You

Wheeler Winston Dixon / University of Nebraska-Lincoln

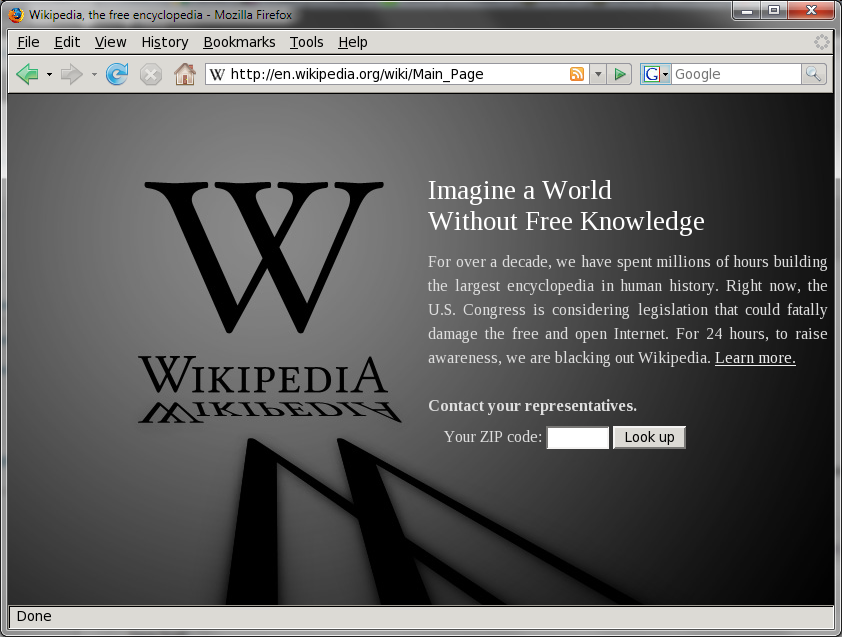

I write this on the morning of the great Wikipedia Blackout, perhaps one of the largest group actions to ever take place on the web. If you try to access the English language version of Wikipedia today, January 18th, 2012, the articles are all blocked with a page blacking out the site, although there are “workarounds,” as Graham Cluley1 wryly observed on the Naked Security website:

“As has been widely reported, Wikipedia is one of a number of high profile websites which is shutting its doors today in protest at US anti-piracy moves. That’s bad news if you’re a student hoping to use your usual trick of scouring Wikipedia for cut-and-paste into your homework. But don’t fear; there’s an easy way to access Wikipedia. Wikipedia’s blackout is achieved using some JavaScript. So, all you need is a trusty copy of the Firefox web browser and the popular NoScript add-on. Simply disable scripts on wikipedia.org and wikimedia.org and . . .Bingo!”

Viewer comments on Cluley’s article enthusiastically adopted this suggestion, with several readers adding that one could “just hit refresh; then as soon as the page shows, hit stop or X according to which browser you use” or alternatively “use Google cache to display the page,” both of which work, so while the blackout may be an effective piece of guerilla theater, it really isn’t a complete “blackout” at all.

But nevertheless, it’s probably the largest, and most widespread web action to take place thus far on the web, and it’s garnered a lot of media attention, both pro and con. And even on Google, the search engine’s famous logo has been blocked out with a large black bar, making it more difficult to use. Inasmuch as Google is certainly a corporate entity, one has to give them points for solidarity on this issue, when it would have been much more convenient for the company to continue business as usual. As Stephanie Condon2 reported in the CBS Political Hotsheet – an appropriate place, it would seem to me, to discuss this action –

“the popular link-sharing site Reddit got the ball rolling for today’s 24-hour Internet blackout. In addition to Reddit and Wikipedia, other sites participating include BoingBoing, Mozilla, WordPress, TwitPic, MoveOn.org and the ICanHasCheezBurger network. Search giant Google is showing its solidarity with a protest doodle [actually a large black bar that entire obscures the site’s logo] and [this] message: “Tell Congress: Please don’t censor the web,” but the site planned no complete blackout. Other sites — like Facebook and Twitter — oppose the legislation in question but aren’t participating in today’s blackout. In addition to the Internet-based protests, some opponents are physically protesting on Wednesday outside of their congressional representatives’ offices. Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian said in Tuesday’s press conference it will “probably be the geekiest, most rational protest ever.”

Why was the blackout necessary? Because the normal channels of communication and persuasion weren’t working. All the companies involved sent a joint letter – some time ago, actually, on November 15, 2011 – to Pat Leahy Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, as well as Chuck Grassley, Lamar Smith, and John Conyers Jr., expressing their “concern with legislative measures that have been introduced in the United States Senate and United States House of Representatives, S. 968 (the “PROTECT IP Act”) and H.R. 3261 (the “Stop Online Piracy Act”).” The letter says, in part, that while the signers of the letter “support the bills’ stated goals — providing additional enforcement tools to combat foreign “rogue” websites that are dedicated to copyright infringement or counterfeiting,” they point out that “the bills as drafted would expose law-abiding U.S. Internet and technology companies to new uncertain liabilities, private rights of action, and technology mandates that would require monitoring of web sites.”3

Lamar Smith initially sponsored the SOPA bill in October 2011. As Declan McCullagh4 notes, while Smith realized that the bill would probably invite some intense discussion,

“the Texas Republican probably never anticipated the broad and fierce outcry from Internet users that SOPA provoked over the last few months [. . .] Smith, a self-described former ranch manager whose congressional district encompasses the cropland and grazing land stretching between Austin and San Antonio, Texas, has become Hollywood’s favorite Republican. The TV, movie, and music industries are the top donors [my emphasis] to his 2012 campaign committee, and he’s been feted by music and movie industry lobbyists at dinners and concerts.”

Given this fact, his advocacy of the bill is hardly surprising. In the industry’s view, as McCullagh5 notes, the whole problem boils down to

“two words: rogue sites. That’s Hollywood’s term for Web sites that happen to be located in a nation more hospitable to copyright infringement than the United States is (in fact, the U.S. is probably the least hospitable jurisdiction in the world for such an endeavor). Because the target is offshore, a lawsuit against the owners in a U.S. court would be futile. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, in a letter to the editor of The New York Times, put it this way:‘Rogue Web sites [. . .] steal America’s innovative and creative products [,] attract more than 53 billion visits a year [,] and threaten more than 19 million American jobs.’”

What do the bills propose to do? In the view of its sponsors, the bills are an attempt to stop pirate web sites operating outside the United States from providing illegally obtained copyrighted content – movies, music, text, images – through American portals. Naturally, industry spokespersons like Christopher Dodd, the former US senator who now has Jack Valenti’s job as head of the Motion Picture Association of America, support both bills vigorously. In a statement on official MPAA letterhead, Dodd6 blasted the then-proposed blackout action, vociferously declaring that

“technology business interests are resorting to stunts that punish their users or turn them into their corporate pawns, rather than coming to the table to find solutions to a problem that all now seem to agree is very real and damaging. It is an irresponsible response and a disservice to people who rely on them for information and use their services. It is also an abuse of power given the freedoms these companies enjoy in the marketplace today. It’s a dangerous and troubling development when the platforms that serve as gateways to information intentionally skew the facts to incite their users in order to further their corporate interests. A so-called “blackout” is yet another gimmick, albeit a dangerous one, designed to punish elected and administration officials who are working diligently to protect American jobs from foreign criminals.”

And certainly movie piracy is a very real concern, one that costs the industry hundreds of millions of dollars every year, at the very least. But what’s the other side of the coin? While Condon states that “Internet companies and their investors would readily say that they’re holding the “blackout” to protect their corporate interests — and the entire burgeoning Internet-based economy” , the reality is far more complex than that. Yes, while such companies as Mozilla, OpenDNS, PayPal, Twitter, The Wikimedia Foundation, Yahoo!, Zynga, The Game Network, AOL, eBay, Etsy, Facebook, foursquare, Google, LinkedIn and others oppose the legislation, so do the ACLU, The American Association of Law Libraries, The American Library Association, The American Society of News Editors, The Association of College And Research Libraries, The Brookings Institute, The Center for Democracy and numerous other groups that aren’t really part of the corporate mainstream. In addition, as McCullagh7 reports,

The European Parliament adopted a resolution last week stressing “the need to protect the integrity of the global Internet and freedom of communication by refraining from unilateral measures to revoke IP addresses or domain names.” Rep. Nancy Pelosi, the House Democratic leader, said in a message on Twitter last week that we “need to find a better solution than SOPA.” A letter signed by Reps. Zoe Lofgren and Anna Eshoo, both California Democrats, and Rep. Ron Paul, the Republican presidential candidate from Texas, predicts that SOPA will invite “an explosion of innovation-killing lawsuits and litigation.” Law professors have also raised concerns.

And indeed, this is a part of the proposed legislation that many people miss. It’s completely US-centric. The web is a global community, and despite the messy problems of crossing international borders, unless we want to shut down the web in a North Korean sort of scenario, we simply can’t, as a nation, unilaterally legislate for the entire globe, although that certainly hasn’t stopped us in the past. As The European Digital Rights8 Website notes,

“In recent years, the United States has been increasingly using the fact that much of the Internet’s infrastructure and key businesses are under US jurisdiction in order to impose sanctions on companies and individuals outside its jurisdiction [. . .] this situation is now turning critical, with legislative proposals such as the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the PROTECT IP Act claiming worldwide jurisdiction for domain names and IP addresses. The definitions in SOPA are so broad that, ultimately, it could be interpreted in a way that would mean that no online resource in the global Internet would be outside US jurisdiction [. . .] On 15 November, over 60 civil and human rights organizations wrote a letter to Congress [. . .] urging the rejection of SOPA. The letter argues that the Act ‘is as unacceptable to the international community as it would be if a foreign country were to impose similar measures on the United States.’9 ”

The proposed legislation’s requirements are many and varied, but ultimately it will have a profound effect on the web, as we know it today, if enacted. The debate currently rages on, and the most recent development, as reported by John Gaudiosi is Barack Obama’s opposition to SOPA. As Gaudiosi10 writes,

The growing anti-SOPA (Stop Online Piracy Act) support that has swept through the gaming and Internet community found a very big ally today. With websites like Reddit and Wikipedia and gaming organizations like Major League Gaming prepared for a blackout on January 18th – the same day that the House Judiciary Committee hearing on HR 3261was scheduled in Washington, DC – President Barack Obama has stepped in and said he would not support the bill. SOPA has been killed, for now. Much to the chagrin of Hollywood, the Entertainment Software Association (which has been a backer of the bill from early on), and Internet domain company GoDaddy.com (which lost many accounts as a result of its support for the bill); SOPA has been shelved. The Motion Picture Association of America, one of the bill’s largest sponsors, is expected to regroup. California congressman Darrell Issa, who has been opposed to the bill from the beginning, praised the Internet action that has swept like a virus across the Web the past week, [saying that] “The voice of the Internet community has been heard. Much more education for members of Congress about the workings of the Internet is essential if anti-piracy legislation is to be workable and achieve broad appeal.”

But as Gaudiosi11 notes, the Enforcing and Protecting American Rights Against Sites Intent on Theft and Exploitation Act [PIPA] is still very much alive, and “legislation [for the bill] is scheduled to go before the Senate on January 24th” 2012. By the time you read this, the IP legislation may or not have become law. But whatever the outcome, the Wikipedia Blackout has made a statement that’s impossible to ignore. It’s pretty much drawn the lines between those who want to restrict the free flow of information across the web, and those who see this legislation as both Draconian and shortsighted.

Certainly the problem of film, music, and text piracy is very real – indeed, I’ve experience this on a personal level, as several of my books have been pirated on the web overseas, and there seems to be precious little that I can do about it. So I’m losing income on that, but at the same time, the information is now more readily available than ever before. Thus, you could say I understand what both sides want in this battle; protection of content on the one hand, vs. freedom of access and information on the other. No matter what happens on January 24th, this isn’t an issue that will be resolved anytime soon. This is just one of the opening salvos in a contest that promises to continue into the foreseeable future, and one which there’s no easy answer to. It will be interesting to see, then, how this plays out over the coming weeks, months, and years.

Postscript: The Wikipedia action seems to have had a significant impact. I write this on the morning of January 19, 2012, just one day after the Blackout, and look what’s happened. As reported by Victoria Slind-Flor12 in Bloomberg Businessweek, “six U.S. lawmakers dropped their support for Hollywood-backed anti-piracy legislation as Google Inc., Wikipedia and other websites protest the measures. Co-sponsors who say they no longer support their own legislation include Senators Marco Rubio, a Florida Republican, Roy Blunt, a Missouri Republican, and Ben Cardin, a Maryland Democrat. Republican Representatives Ben Quayle of Arizona, Lee Terry of Nebraska, and Dennis Ross of Florida also said they would withdraw their backing of the House bill.”

When the Wikipedia site returned on line, it did so with a message to its users, which read in part “More than 150 million people saw our message asking if you could imagine a world without free knowledge. You said no. You shut down Congress’ switchboards. You melted their servers. Your voice was loud and strong. Millions of people have spoken in defense of a free and open internet,” but the battle still continues. As Wikipedia concludes in their message, “SOPA and PIPA are not dead: they are waiting in the shadows. What’s happened in the last 24 hours, though, is extraordinary. The Internet has enabled creativity, knowledge, and innovation to shine, and as Wikipedia went dark, you’ve directed your energy to protecting it. We’re turning the lights back on. Help us keep them shining brightly.”

Image Credits:

1. Wikipedia Blackout

2. Google Black Bar

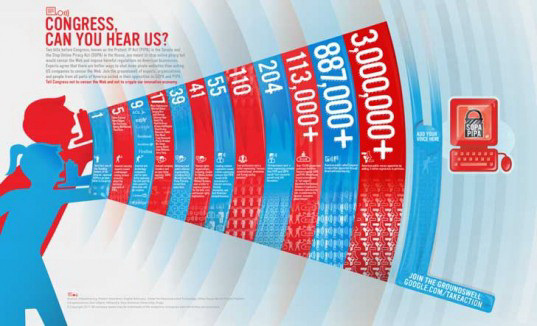

3. SOPA Blackout Success

Please feel free to comment.

- Cluley, Graham. “How to Get Around the Wikipedia Blackout,” Naked Security January 18, 2012. Web. [↩]

- Condon, Stephanie. “SOPA, PIPA: What You Need to Know,” CBS News Political Hotsheet, January 18, 2012. Web. [↩]

- AOL, et al. “Letter to Chuck Grassley, Lamar Smith, and John Conyers Jr.,” November 15, 2011. (See pdf attached). [↩]

- McCullagh, Declan. “How SOPA Would Affect You: FAQ,” CNET, December 21, 2011. Web. [↩]

- McCullagh, Declan. “How SOPA Would Affect You: FAQ,” CNET, December 21, 2011. Web. [↩]

- Dodd, Christopher. “Statement on the So-Called ‘Blackout Day’ Protesting Anti-Piracy Legislation,” MPAA Website, January 17, 2012. Web. (See pdf attached). [↩]

- McCullagh, Declan. “How SOPA Would Affect You: FAQ,” CNET, December 21, 2011. Web. [↩]

- “European Parliament Warns of Global Dangers of US Domain Revocation Proposals,” European Digital Rights, November 17, 2011. [↩]

- Access, et al. “Letter Opposing H.R. 3261, the Stop Online Piracy Act,” November 15, 2011. (See pdf attached.) [↩]

- Gaudiosi, John. “Obama Says So Long SOPA, Killing Controversial Internet Piracy Legislation,” Forbes, January 16, 2012. Web. [↩]

- Gaudiosi, John. “Obama Says So Long SOPA, Killing Controversial Internet Piracy Legislation,” Forbes, January 16, 2012. Web. [↩]

- Slind-Flor, Victoria. “SOPA, Spider-Man, Alcatel-Lucent: Intellectual Property,” Bloomberg Businessweek, January 19, 2012. Web. [↩]

Thank you for the great article! While the legislation itself was finally put to rest, it would not surprise me if the ideas behind SOPA will continue to still be an issue in the future of US politics.

I’ve been watching the controversy over SOPA since December. What interests me is the fact that it brings out a lot of important issues that rarely get discussed openly: corporate power, modern censorship, American imperialism, etc. The fact that there are people who not only thought that SOPA was a good idea, but also thought that it would pass easily (which was very possible before they awakened the wrath of the internet), is disturbing to say the least. With this being said, the justified outrage over the bill is encouraging– even in this day and age, people still will unite to stand up for something they believe in (even if it is just their ability to use Wikipedia).

Of course, the companies on either side of the issue are taking their stance because it protects their own interests. With such powerful legislation as SOPA, these companies would have been foolish not to do so. This is one of the rare times when certain corporate interests, such as those voiced by the tech companies opposed to the bill, seem to be in line with the interests of a large number of Americans (and many people around world, for that matter). I think that may be where the proponents of the bill went wrong: they didn’t realize that their legislation would not only hurt the so called “criminals” that they were going after, but also average people who just want to participate in an open, global form of human interaction. People don’t actually use the internet like the large media corporations would like them to. A relatively free flow of information allows people to remix and rethink media, to interact with it in new ways. Sometimes what seems like a copyright violation to a large corporation is really a fan video or a form of self-expression. Where copyright ends and fair use begins is only getting more complicated.

I’m glad that you touched on the fact that the US is trying to prevent criminal activity outside its borders. This was perhaps the most infuriating part of the bill. I know we’re a global superpower, etc, but the US needs to learn that this does not give us the right to legislate for the entire planet. If the situation were reversed, I think many people would be up in arms over the perceived intrusion by a foreign nation into our politics. On the other hand, one thing that has often been overlooked is the fact that the bill also contains measures against counterfeit goods. While intellectual property rights and anti-counterfeiting go hand in hand, the odd mixture of digital and physical products is telling of the legislator’s attitudes towards things like online piracy. While both counterfeiting and online piracy involve the creation of illegal products, the differences between the two crimes seem so obvious to me that I am surprised that they are included in the same bill. Counterfeiting involves the creation of a physical product, often for sale. Digital forms of copyright infringement, like digital piracy, however, is often more benign. While some people do sell pirated media, not all piracy involves a profit. Furthermore, the product is identical to the one available legally; usually the only difference between the two is the way in which they were acquired. The file may contain viruses, but the good is not nearly as dangerous as a counterfeit drug, for example. I understand the similarities between these various crimes, but it seems to me that perhaps online and offline copyright infringement is too big of an issue to cover together in one bill. Doing so, however, reveals the attitudes of the legislation’s creators towards the problem, and perhaps their inability to see the nuances of the issue.

I could go on about SOPA and what it means from an aspiring media scholar/internet user’s point of view, but I think you get the point. SOPA is a great snapshot of media and law in modern times and it cracked open a lot of issues that have been brewing related to copyright and the internet. While the main fight is over, no doubt we will see these issues coming up again in the future.