The Thirtieth Anniversary of Roots and the Deferred Dream of Black Drama

Tim Havens / University of Iowa

The thirtieth anniversary of the smash ABC miniseries Roots (1977) came and went with little fanfare. TV One reran the miniseries a couple of times with extensive on-channel promotion, and Warner Bros. re-released the miniseries on DVD. As we enter a post-network television era, however, it is worth reassessing the promises and disappointments that came in the wake of Roots in order to understand the prospects for African American television today, especially dramatic series.

Roots was the first major television drama featuring African American actors, themes, and stories. In addition to posting a record-breaking 72-share for its final installment, the miniseries raised the hopes of African American viewers and actors that the long drought of African American televised drama might finally be over. Alas, those hopes have gone largely unfulfilled.

Why this persistent lack of African American drama on mainstream television, even after Roots demonstrated the potential popularity? If one listens to industry insiders, African American drama is simply an economic impossibility. White viewers aren’t interested in black drama, and black audiences alone don’t warrant the kind of production investment that television dramas require. I want to question that wisdom, because I believe that it stems from a number of blind spots about race, culture and economics.

The absence of African American drama today owes mainly to perceptions of international buyers’ preferences, because dramas requires good international sales to make back production deficits. Perception of international preferences, in turn, are based on what I want to call “industry lore,” or a set of assumptions about cultural and economic realities that shape industry insiders’ beliefs about what is and is not possible in television.

African American dramas, even those with only one or two prominent black characters, are generally seen as unsaleable abroad. In comments posted here (at the 1 hr., 1 min, 30 second mark), for instance, Susanne Daniels, President of Entertainment for Lifetime Entertainment Services, explains why prime time features so few dramas starring African American women:

I’ve frequently heard this sentiment from television executives, but never in such a public forum. Obviously, the perception is widespread. Daniels’ comments give us a window into how industry lore works, so before pursuing my counter-example of Roots, I want to talk briefly about industry lore.

Industry lore comprises common sense knowledge about audience preference and the possibilities of the medium that get passed along in many forms, including trade journals articles and informal executive education. Often, industry lore draws on particular examples to illustrate more general truths. The fact that predominantly Muslim Egyptian audiences rejected Gunsmoke because Matt Dillon’s badge resembled a Star of David, for instance, provides a general lesson about the dangers of cultural ignorance when selling programs internationally. These features of educative storytelling are what lead me to use the term “lore,” which the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary defines as “traditional knowledge and stories about a subject,” rather than a more general term like discourse.

Industry lore facilitates the smooth operation of the commercial television industries. Television markets are purely imaginary. Conceptualizing which audiences might be interested in which programs is an act of imagination, even when it is backed up by research, which is seldom the case in international television trade. Industry lore is the product of those collective imaginings. Finally, industry lore is a form of material discourse, which derives from and acts upon other material processes of the television business, including political-economic forces, industry organization, and day-to-day business practices.

In the case of Roots, industry lore at first worked against the worldwide distribution of the miniseries; then, after it became “the world’s most-watched television drama,”1 industry lore stepped in to downplay the importance of the African American elements in the show’s global appeal. Letters from Roots producer David Wolper to the international distribution units of United Artists and Twentieth Century-Fox, as well as acquisitions executives at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Canadian distributor Simcom, the BBC, and Australian Channel 7 show that Wolper worked hard to find outlets abroad for the miniseries, but generally failed. While American distributors uniformly praised the miniseries, they agreed that “the primary market for the project would be the U.S. and Canada”2 and they did “not believe that much [could] be done with it overseas.”3

Obviously, distributors believed that viewers abroad would have no cultural frame of reference to understand African American experiences of slavery. Nevertheless, the miniseries sold in 49 territories in its first two years of syndication, and it earned as much abroad as it did in domestic syndication. Industry insiders took two lessons away from Roots’ surprise global appeal: that buyers abroad, especially hard-to-crack European public broadcasters, were interested in miniseries because they fit the scheduling demands of non-commercial channels; second, that historical miniseries rooted in “universal themes” could appeal to foreign viewers.

Roots inaugurated a cycle, in which African American television programs break new ground in international markets, only to pave the way for white series to follow. Roots paved the way for predominantly white historical miniseries. The Cosby Show paved the way for predominantly white middle-class sitcom sales abroad. And The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air paved the way for predominantly white youth programs (though the story here is more complex.)

Why does this pattern recur? Obviously, the disproportionate wealth of European buyers helps explain why those markets drive domestic production decisions more than others. In Roots‘ time, international sales were central to funding the elaborate miniseries genre, much as is the case with dramatic series today. But cultural assumptions, in the form of industry lore, play a crucial role as well. The fragmentary evidence about the reception of Roots abroad suggests that, for some viewers, the story of black suffering was central to their interest in the program, even if that story was melo-dramatized and advocated patient perseverance. The prevalent industry lore, however, erased the specifics of African American history as an explanation of Roots’ success, zeroing in instead on those elements such as historical themes that could more easily be applied to white stories, fitting industry perceptions of their primary audience at home and abroad. Of course, the idea that shared racial identities or historical settings can overcome national cultural differences is rooted in some very specific assumptions about cultural identity and difference.

The irony for African American programs is that, despite their path-breaking sales records, they frequently get pegged as too pedestrian for foreign viewers. This is not so much an example of overt racism on the part of industry insiders as it is a demonstration of how immersed most of them are in white cultural assumptions. They see white culture as universal; in fact, they can’t really see white culture at all, but only non-white culture. For them, the absence of non-white cultural values and allusions is the presence of universal themes.

The economics of the industry have changed dramatically since the days of Roots, with new transnational funding arrangements, new crops of buyers targeting sub-national and transnational audience niches, and an explosion of format sales. Industry lore has likewise become more contested and multi-vocal. But industry lore about African American programming has remained largely unchanged, and until it does, the prospects for African American drama remain dim, as does recognition of the central role that black culture has played in worldwide flows of television culture.

—

I would like to thank the David L. Wolper Center at the University of Southern California for access to their records, and especially Sona Basmadjian for her invaluable assistance.

Image Credits:

1. Roots DVD

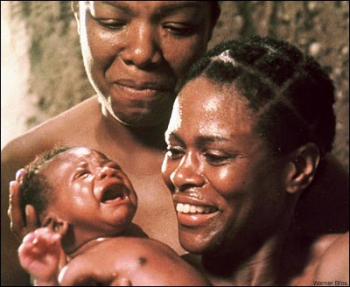

2. Maya Angelou and Cicely Tyson

3. Roots BBC

Please feel free to comment.

- Warner Bros. promotional kit for Roots. Undated. David L. Wolper Center archives no. 283-006. [↩]

- Letter from Danton Rissner, Vice President in Charge of East Coast and European Production for United Artists Corporation to David L. Wolper, March 1976. David L. Wolper Center archives no. 282-016. [↩]

- Letter from David Raphel, President, Twentieth Century-Fox International Corporation to David Wolper, March 1, 1976. David L. Wolper Center archives no.282-016 [↩]

It seems as if the American market can’t get past Slavery and Civil rights as subject material for Black American drama and it’s many voices. Are shows that talk about racial discrimination seen as non-progressive and therefore deviant? Are these images offensive due to the fear that Black American dramas will challenge, or criticize the status quo of White America or are they merely seen as “static” images that can’t address global social issues? Whatever the reason Black America and Black American TV images remain an anomaly pigeon-holed into being unable to relate to the rest of the world when the stories shared by all races and ethnicities are universal.

Thanks for the comment, Kevin.

I think the question of why African American shows aren’t more prevalent and diverse has to do with fear and uncertainty on the part of industry execs, who (a) don’t think black stories are interesting to non-blacks and (b) don’t want to get branded as “black” channels for fear they won;t draw non-black viewers.

Personally, I think there’s overwhelming evidence that black Atlantic culture has a much longer and richer history of transnational exchange than does white European and American culture.

But then, the industry execs I know rarely ask me for my opinion on these matters…..

Thank you for this. As I was reading it, I was thinking about complicated shows like “Oz” and “The Wire” which seem to have appeal across “the racial divide,” but which also seem to promulgate a very specific type of blackness that is experienced by very few folks. Those are cable shows, obviously, but I am wondering about production models in cable vs broadcast (where Chitlin Circus antics are reigning supreme). Are you going to take the research further and think about the disparities in subject matter in relation to industry type/scale? Your piece also really had me thinking about the blog “stuff white people like” and the ways in which whiteness is not allowed to be perceived as a practice, but as IS. and then what that does to other practices in contact with it. in the case of your research, “white people don’t like serious negroes” as accepted lore is striking…but we’ve all trafficked in that. thanks for showing how it works in the numbers.

I find it amazing/appalling that the industry could honestly believe that the world wouldn’t be interested in stories about African Americans. My experience (both personal and from interviews) is that much of the world is (getting) sick and tired of endless Great White American tales. I guess Hollywood doesn’t get that the African American experience of marginalization within White America might to many international viewers seem quite close to their own experience of being marginalized on an America First planet.

The industry lore reeks, as you note.