The Anachronism of Television Subscription Packages

Recent events in the television industry warrant reconsideration of the ways by which television channels come into our homes, and what options we as media consumers have in choosing which television channels we can and want to see. Many Americans get television content through subscription packages, available from cable or satellite service providers, which allow for more options and content than what is available over the public airwaves. This subscription-versus-free content distinction is nothing new. Other media incorporate technologies and models that split between free and subscription services, and we may even consider WiFi hotspots in a similar context. But it is the manner in which subscription television is made available to consumers that is under discussion at the present moment. Most specifically, I’m interested in the ways consumer choices over TV selections, and the public discourse these choices have generated, reveal television subscription providers’ antiquated attitudes toward media production and availability in contemporary society.

What makes this issue particularly compelling is that television is practically a national institution, and receives the kind of public, governmental, and commercial attention afforded such status. The upcoming conversion in 2009 from analog to digital broadcasting has prompted cable companies, legislatures, and other media advisory groups to work hard to help consumers keep their televisual lifestyles, including spending $200 million in consumer education and establishing a $1.5 billion Congressional subsidy for converter box upgrades (Van Wyk & Johnson, 2007). Nothing of this sort was offered to satellite radio or to help most households make the switch from dial-up to broadband Internet services. Such assistance speaks not only to the type of content available through television (e.g., public service announcements and local news) but also its apparent inextricability from Americans’ media ideology. But such measures only deal with making sure Americans with televisions have access to the basic set of channels. At a different point on the spectrum, much concern is being expressed over the kinds of television choices paying cable customers have available to them, and why these choices are not more accommodating.

The basic fact is that television subscription services are not accommodating to an individual customer’s desires. A person cannot contact their subscription provider, tell them the channels they want, and then ask for a rate that covers only those channels. Most television channels are not offered as solitary subscription selections. Moreover, one cannot “swap” television channels from one package to another. This inability to customize content selection fails to recognize and stands in sharp contrast to the prevailing attitudes in contemporary media – namely, that we are living in an era when consumers feel entitled to content selectability. True, this may be an unearned sense of entitlement, but it is present nonetheless and supported by other media outlets. When I rent a movie from my video store, I do not have to rent three other videos along with it as a “package.” Nor do I have to subscribe to the New York Times in order to get a subscription to my local newspaper. In order to get CNN on my television, however, I must subscribe to a package that contains many other channels I may not want, and leaves out a few channels I wish I had. Compared with these other media outlets, packaging TV channels seems increasingly anachronistic. Perhaps no other venue demonstrates this disconnect better than the network websites for many of these channels, which offer many of their programs online for free and on demand, demonstrating to cable providers that such selectability is possible in this modern media age. We can readily observe the widening disjuncture between consumers who desire selective, on demand content, and television subscription services which favor instead the idea of offering amalgamated television.

This lack of flexibility has become the object of pointed ridicule in a recent ad for the NFL Network, in which the denizens of a diner challenge a cable company employee’s statement that cable companies “can’t charge people for channels they don’t want,” suggesting that the reason why the NFL Network is not carried by more subscription services is because there is not a market for it. To the obvious discomfort of the cable employee, the other diner customers then list the number of channels they have to pay for, but do not want, as part of their subscription packages. The gist of the commercial – which encourages viewers to join a campaign to get television providers to offer the NFL Network – is that cable companies arrogantly assume that they know the television wants of consumers better than the consumers themselves. What gives the commercial its bite is an underlying ideology that the consumer’s idiosyncratic demands should always be met.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VsB6sGhK434[/youtube]

Indeed, this ideology has allowed specific antagonisms to develop, demonstrated in the rhetoric of the NFL Network which claims that cable companies are “abusing [their] power” and “holding fans hostage” by not accommodating their television wants (“www.iwantmynflnetwork.com”). After the NFL decided to allow the season-ender between the New England Patriots and the New York Giants, originally scheduled to air only on the NFL Network, to be simultaneously broadcast on NBC and CBS, the move was hailed as a victory for fans, who watched in record numbers (“34.5 Million Watch,” 2007). When fans do not have to negotiate the maze of cable subscription packages, television proves it can still draw in appreciative viewers who want what TV provides best. But the positive resolution of this story should not overshadow the fact that fans were caught in the middle of television’s anti-choice mindset, and that this was noticed and commented on as a failure on the part of TV content providers. As one report explained regarding the broadcast, “The NFL had claimed that the onus of making the game widely available fell on the major cable providers with which the league has bitterly feuded. Other cable companies such as Comcast and Time Warner have declined to carry the network as part of basic packages” (“NFL to Simulcast,” 2007). While it may be overly-dramatic to claim, as the NFL Network does, that such feuding holds viewers “hostage,” what becomes clear from these comments is that the television subscription mechanism for delivering content to viewers is not simply antiquated, but in danger of collapsing on itself. The squabbling between subscription providers and entities like the NFL even has been noticed by members of Congress, who recently issued a not-so-veiled warning to the NFL and cable providers that consumers’ abilities to get the media content they want via television will be closely protected (“Senators Threaten NFL,” 2007).

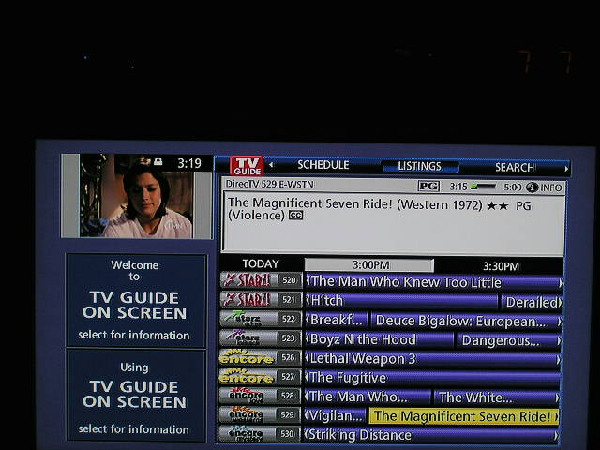

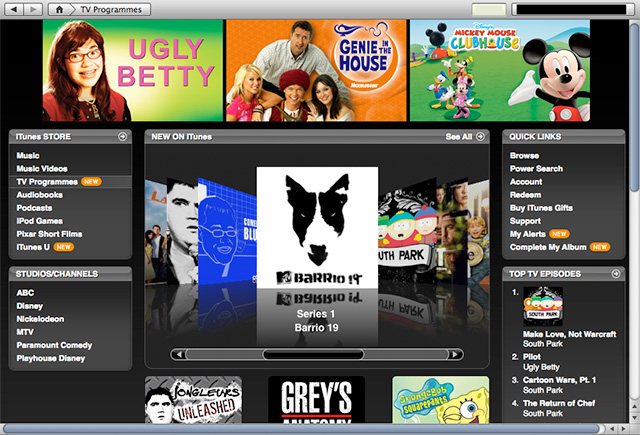

What these comments speak to is a feeling about how far removed television has become from the current trends in consumer media. Television shows can be found on iTunes, video rental stores, and networks’ own websites not long after they air, but cable companies recognize no such preference for individual selectability. This stance has thrown many of the cable companies’ own words into a contradictory light. Companies like Bresnan Communications, a subscription cable provider, claim “It’s personal” as their corporate slogan, but require customers to subscribe to packages that would be hard to justify as satisfying the personal desires of individual cable customers. Other cable companies like DirectTV and Time Warner air commercials for themselves explaining how their service offers more choice over their competitors’, but both require their customers to subscribe to packages. The “choice” being offered is simply over who provides the packages, but the packages themselves are strikingly similar and non-negotiable for individual consumers. If television viewers are not able to use that medium to gain access to the content they want when they want it, then the medium itself can only continue to make itself an increasingly irrelevant part of that viewer’s media lifestyle. One recent survey by IBM, for example, indicates that younger generations are trending away from television time in favor of other media time, predominantly the Internet (“IBM Consumer Survey,” 2007). Without a justification for such obstinacy on the part of the cable companies, one could not blame viewers for abandoning television for other venues more accommodating to their media desires and whims.

Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to note a positive aspect of the current situation – not so much in terms of economic advantages to cable companies, but of how the subscription package mechanism provides at least one distinct advantage for consumers. Having more channels than one may want occasionally may mean that someone will serendipitously come across a program that will benefit them in unpredictable ways. This is the situation discussed in part by Cass Sunstein (2001), who noted that consumers who expose themselves only to media content based on their current ideologies are in a worse position as citizens than those who are forced to encounter a wider variety of perspectives, even those not of their own choosing (pp. 8-9, 153). A diversity of opinion, even if encountered reluctantly, is better than a homogeneity of opinion. This argument may apply equally well to other media. While iTunes consumers complain about some albums whose tracks are not individually purchasable, all music consumers likely can relate to the opposite and enjoyable experience of coming across a music track on an album that they would never have heard but for having to purchase the entire album. But these encounters are more about luck than intent. Put differently, these happy incidents of culture come about not because media producers encourage consumers to broaden their horizons, but because consumers are forced into having to opt for more than they want.

A more satisfying and attentive model of television production, distribution, and consumption would provide desirable opportunities for media consumers to be exposed to and consider a diversity of media offerings without feeling like it was something they were forced in to. Other media outlets are doing this, while subscription television continues to insist that its mode of providing content is neither negotiable nor in need of reconsideration. How long television can thrive under such circumstances remains to be seen, but what is clear is that the competition from other media sources is gaining – and quickly. Looking at the anachronism of television subscription packages suggests that the fate of television’s cultural relevancy in the modern media age has much to do with how it is made available to consumers, as much if not more so than what is actually broadcast.

Image Credits:

1. Cable Channels made available en masse

2. Campaign mounted by NFL Network

3. TV on iTunes

Works Cited

34.5 million watch Patriots’ historic win. (2007, December 30). MSNBC.com. Retrieved December 31, 2007, from the WWW: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22443488/

IBM Consumer Survey Shows Decline of TV as Primary Media Device. (2007, August 22). Retrieved January 3, 2008, from the WWW:

http://www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/22206.wss

NFL to simulcast Pats-Giants on NBC, CBS. (2007, December 26). MSNBC.com. Retrieved December 31, 2007, from the WWW: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22400789/

Senators threaten NFL over NFL Network. (2007, December 19). MSNBC.com. Retrieved December 31, 2007, from the WWW: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22331857/

Sunstein, Cass. (2001). republic.com. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Van Wyk, R., and Johnson, A. (2007, December 31). Better TV is coming, but are you ready for it? MSNBC.com. Retrieved December 31, 2007, from the WWW: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22401907/

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: roblef dot com » Blog Archive » good point

Pingback: roblef dot com » Blog Archive » another good point

Historically there has been a role for packaged or “bundled” cable and satellite programming — as a means of assuring payment for less popular channels. Subscribers have to pay for basic channels they don’t intend to watch in order to get those they do. As someone far more likely to watch one of the multiple Discovery networks than one of the popular ESPN networks, I can appreciate this, even as I see it as a consequence of a haphazardly planned U.S. television funding system writ large.

During a key phase of multichannel television’s development (say the 1980s and 1990s) , bundling within a loosely regulated economic systems surprisingly fostered the growth of someo eclectic and interesting programming on cable. I appreciate this, even though ti contradicts some of my more typical political positions.

New broadband technologies and the distribution economics they bring will undoubtedly compel television providers of all kinds to offer à la carte programming, bypassing the network system entirely.

But we needed that in-between bundling state given what there was to work with.