Therapy is Complicated: HBO’s Foray into Modular Storytelling with In Treatment

The potential revelatory intensity of the therapy session may not be particularly cinematic, but it has sure proven televisual, especially recently—and especially on HBO. The therapy session, when not written for laughs, is a challenge, and an easy crutch for bad writing as a pre-determined staging instrument for airing pained interiority, in conflict with the “show, don’t tell” principle. HBO’s most recent trips to the couch (The Sopranos, Tell Me You Love Me) have been moderately used, nestled within broader action, a variety of locations, and wider story frame. Not so with its new series, In Treatment, an adaptation of the Israeli Betipul, premiering next week (January 28, 9:30 ET). Here, the treatment, the Tell, is all.

The Israeli original, created by Hagai Levi, the son of two therapists and a veteran of Israeli telenovelas, and Ori Sivan, a self-described “therapy true-believer” became a cultural phenomenon. Winner of virtually every television award, and proclaimed by critics as “the most important achievement in a drama series” and “the best Israeli television show ever,” Betipul (literally “in treatment”) was noted for an unprecedented one million video-on-demand downloads in its cable run (nearly half of all Israeli households). The show’s casting alone identified it as the epitome of Israeli quality drama: Leading the cast of Israel’s cinematic elites was acclaimed actor-writer-director Assi Dayan (son of Moshe Dayan and known as much for his public outbursts, volatile personality and critiques of the Israeli right, as he is for an impressive body of cinematic work) as the psychiatrist, Reuven Dagan; Gila Almagor (“first lady” of Israeli stage and screen, described by one critic as “the Israeli Judy Dench”) as Reuven’s therapist and past mentor, Gila; and several of Israel’s most recognized stars, led by Ayelet Zorer and Lior Ashkenazi (familiar to some U.S. film audiences; Ashkenazi for Walk on Water and Late Wedding and Zorer for Nina’s Tragedies and Munich).

But it was most noteworthy for its format: The program ran nightly, in half-hour segments for five nights each week. Monday through Thursday, the psychiatrist held appointments with that day’s regular patient; on Friday, he met with his own therapist. On-demand and DVD options allowed further flexibility in the audience’s experience of the narrative: Viewers could watch the show in chronological order (a week at a time), or follow any particular patient’s storyline individually.

The patients, at first glance, presented the usual grab bag of psychological dysfunctions, frayed relationships and pained histories. Yet, overtime, their revelations, in parallel with Reuven’s own crisis, offer a particularly riveting and televisually-specific narrative structure. Na’ama is a young paramedic with daddy issues who precipitates Reuven’s unraveling with her insistence that their relationship go beyond therapy. Orna and Michael are a couple contemplating an abortion as their own relationship deteriorates. Teenager Ayala is a promising gymnast who’s suspicious accident appears more and more like a suicide attempt.

Yadin is a cocky fighter pilot, who seems chillingly indifferent to the carnage he caused after bombing a Palestinian apartment building and who’s own gradual deterioration serves to deconstruct the crushing consequences of Israel’s military ideology. At the end of each week, as Reuven unloads his rage and confusion over his failing marriage and his panic that his clinical skills are also failing, he struggles with his ex-mentor, Gila, as their own complex history and contained hostility seep through the professional veneer of their counseling sessions.

The American version, by several accounts, is remarkably similar (one member of the production asserts that the script was not so much “written but translated”). This is worth noting because even in Israel, where TV dialogue (and cultural norms) eschews reserved politeness in favor of blunt antagonism, the raw intimacy in the confrontations between the psychiatrist and his patients drew attention and public discussion. Pointedly, the only cultural translation the American version struggled with was the character of Yadin Yerushalmi, the fighter pilot. Blair Underwood was cast early for the role and his professional identity was tweaked repeatedly before settling on Alex, a navy fighter pilot, recently returned from Iraq.

Advance word on HBO’s adaptation has focused on its scheduling strategy and HBO’s decision to maintain the original airing structure: 45 episodes in total, spread into five 30 minute episodes a week for a total of nine weeks. Some critics and posters in online forums expressed bafflement at the format, and speculated the show could prove boring, too complicated or too talkie for an American audience. (Interestingly, on discussion boards, it is often the Israeli-Americans, familiar with the original—the DVD pack is a hot commodity among expats—who post explanation on how the show works, assuring others that it’s “not so complicated.”)

HBO’s strategy for scheduling and promoting the show, however, are not only cognizant of the fact that a large portion of it audience has no intention of watching the show in its scheduled time slot, but playfully encourage the show’s temporal flexibility, tying it, as did the Israeli version, with its narrative structure. In addition to its nightly airing on its main and HD channels, the previous week’s full session will be available each Monday on HBO On-Demand and, starting the following week, HBO Signature will air sessions daily according to the characters’ weekly appointment times: 9 a.m. Monday morning for the erotically-charged session with Laura (Melissa George); 10 a.m. on Tuesday for Navy pilot Alex (Blair Underwood); 4 p.m. on Wednesday for the young gymnast, Sophie (Mia Wasikowaska); 6 p.m. on Thursday for Amy and Jake (Embeth Davidtz and Josh Charles); and 7 p.m. on Friday for the show-down with Gina (Diane Wiest). This “fiction driven” scheduling strategy fosters the kind of variety in viewing experiences, posing the possibility of a single-character viewing option as a separate, weekly installment.

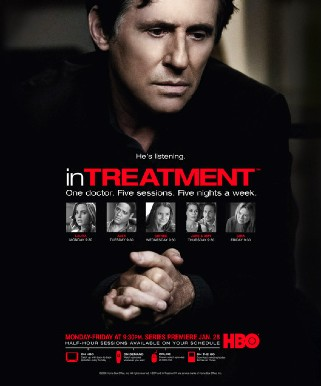

HBO’s poster further emphasizes flexible delivery of content, weaving such a flexibility into the show’s narrative logic: Note the tag line “Half-hour sessions available on your schedule.”

While Israeli television productions (especially format game shows and produced telenovelas) are regularly purchased for international adaptation—most commonly in Eastern Europe and Latin America—Betipul is the first show to be picked up for the U.S. market and is widely considered a coup in Israel. In the global television market, the U.S. is unusual, of course, because it rarely imports non-format TV shows. What’s more, historically (consider All in the Family, Absolutely Fabulous or Ugly Betty, as some touchstone shows) U.S. adaptations are generally aggressively localized in content and often in narrative structure (perhaps The Office is a sign of change here, considering the successful preservation of the show’s timing and tonality). Ugly Betty may, however, be the most useful signpost to end on here, as the global wave of its recent adaptation has brought more attention (in the English-speaking market in U.S., especially) to the global phenomenon of telenovelas. And, as this narrative format’s origin story often begins with U.S. soap imports’ circulation within Latin America, the U.S. adaptation of an Israeli generic hybrid of the telenovela and “quality” TV drama brings us back again, in full circle.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MpLf3MhA32A[/youtube]

Image Credits:

1. Betipul cast

2. Ayala (Maya Maron) in Betipul, screen captured image provided by author.

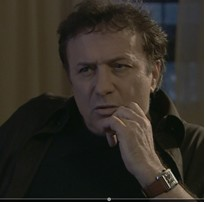

3. Assi Dayan as Reuven, ibid.

4. Gila Almagor as Gila, ibid.

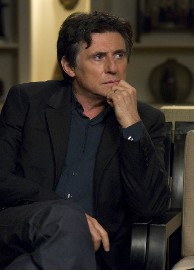

5. Gabriel Byrne as Paul

6. Diane Wiest as Gina in HBO’s In Treatment

7. Underwood as Alex with Byrne

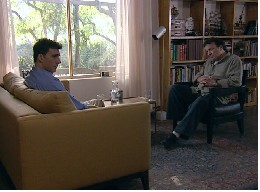

8. Ashkenazi as Yadin with Dayan, screen captured image provided by author.

9. In Treatment promotional poster

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: roblef dot com » Blog Archive » new show

Pingback: roblef dot com » Blog Archive » links for 2008-01-23

I’m loving that HBO seems to be one of the first TV channels to try and explode traditional linear programming patterns, given the reality that many viewers are trending away from those patterns anyway. I’m not up to snuff, though on my TV history — has something like this been tried before?

I’ll be very curious to see how this show is received. I’m also wondering if they have any Internet distribution plans… although it seems like the HBO DVD box sets are worth a mint to the company in general, and as you mention, the DVD set of the Israeli version is a hot item.

Now if only I had HBO… :)