Ownership and Desire: Fans’ and Producers’ Polymorphous Triangulations

Although heralded by critics as a sophisticated reinvention of science fiction, the 2004 version of Battlestar Galactica also reserves significant screen time and receives significant fan devotion for its portrayal of romance and love triangles. Often denigrated as “low” entertainment, the use of prolonged, convoluted courtship narratives to sustain viewers’ emotional involvement may appear paradoxical for the critically acclaimed new Battlestar. However, as Battlestar Galactica continues to make itself (in)famous for launching drastic changes in cast, location, purpose, and characterization with little or no notice, its writers and producers walk a fine line, both depending upon and toying with viewers’ affections as they manipulate beloved characters’ romantic destinies. Eve Sedgwick theorized that Victorian literary romantic triangles sustain intense attraction and aggression while establishing equivalence between antagonists for a shared object.1 Analogously, fans propose their own equivalence to culture industry producers by retaining their investments in non-canonical romantic relationships even after the “official” narrative triangle collapses on-screen, sometimes postulating an alternate, independent existence for their couple of greater value than the professional version. Thus producers’ and fans’ negotiation of the ownership and control of present-day popular culture and mythology manifests in passionate parallel triangulations through the shared romantic object; as fictional characters vie for libidinal fulfillment, they also stage larger struggles over the value and validity of viewers’ libidinal investments.

Battlestar Galactica’s use and abuse of its viewers’ affections offer one lens for thinking about the way that audiences interact with producers’ intentions and genre conventions in a media environment increasingly characterized by postmodern genre hybridity and convergence. Two other case studies outline similar tensions at play when producers and academics attempt to come to grips with increasingly heterogeneous, stratified, and vocal audiences. First, in his 2002 book Using the Force, Will Brooker discusses the “Campaign for a Female Boba Fett,” a web project designed by a female Star Wars fan both to convince other fans that the Boba Fett of the original trilogy could have been female and to convince George Lucas to explicitly make her so by casting an actress to play Fett in the prequels.2 Citing Lucas’ characterization of Star Wars as a “boys’ film,” Brooker questions what devotees of a female Boba Fett will do after the prequels explicitly assign a male sex and gender to the character. To some extent Brooker’s concerns derive from the site owner’s explicit intention to see her investment appear on screen. However, given that the web page moved to a new service provider and still appears fairly active even years after a professionally produced male Fett appeared on-screen, the suggestion that additional source material may render void the pleasures that viewers find in earlier material seems fundamentally inadequate.3 Fan enjoyment in thinking about Boba Fett as a woman does not simply evaporate in the face of a louder pronouncement of George Lucas’s intentions and pleasures. Yet, this anecdote also outlines the unequal struggle waged between producers and groups of fans over the fate of serialized film and television narratives.

As a second example of the challenges presented by multi-vocal audiences, Scott Rogers presented a paper at the 2007 Southwest/Texas Popular Culture and American Culture Associations Conference on Lost fans and their extensive inter-media networks for gathering and sharing information pertinent to the program’s slowly revealed puzzle.4 While Rogers argued that fans work collaboratively, he also characterized their activities as inherently competitive because individuals race to be the first to figure out all of Lost’s clues. In the question and answer period Rogers readily allowed that his population of interest represented merely one of many entrances into Lost viewership, but he seemed unable to imagine the nature of other viewers’ interests and investments. Thus, he discounted the possibility that Lost will provide anything to inspire fans’ continued involvement once all the island’s puzzles have been revealed, largely because he had previously argued that viewers couldn’t possibly be interested in the dramas of individual characters’ lives apart from those characters’ roles as puzzle pieces. Yet, even when cataclysmic events further Lost’s momentum toward its endgame, many viewers mourn the loss of beloved characters whom they would rather see week after week as happy and fulfilled, or at least growing and interacting, than as dead but symbolically useful. The inability to theorize both romantic and analytic pleasures simultaneously, as well as to infer the emergence of entirely new patterns of viewership, represent central challenges in the analysis of new media and hybrid genres.

These anecdotes begin to suggest the difficulties involved in studying hybrid genres and their stratified audiences, particularly as academics and producers attempt to come to grips with a range of pleasures traditionally coded as feminine. In his discussions of “convergence culture” as exemplified by the program Heroes, Henry Jenkins writes that producers have increasingly turned to elements of melodrama, soap opera, and romance to ensure a wider audience for otherwise traditionally masculine-coded genres like science fiction.5 Rather than functioning merely as supporting or tertiary storylines, Jenkins argues that characters’ growth and interpersonal relationships have become the central focus for a wave of characteristically postmodern, genre-crossing new television programs like Lost, Heroes, and Battlestar Galactica. However, if, as Jenkins argues, producers have infused androcentric genre codes with supposedly “female” storylines due to viewer demand, these elements often remain strange bedfellows and require constant delicate negotiations between producers, writers, and various groups of fans who often find fulfillment in a program for vastly different reasons.

Thus, by juggling all of the potential payoffs and narrative arcs associated with science fiction, the romance, and soap opera, Battlestar Galactica treads a fine line, always risking the alienation of one or another market share with each narrative decision. Particularly, sudden compound triangulations of on-screen relationships which had seemed fairly fixed and headed toward what many fans saw as a fulfilling romantic conclusions have resulted in heated on-line debates. Commentators charged producers and fellow fans with racism, sexism, homophobia, ageism, and sundry other vices based on the position that each implied by preferring or performing one or another conclusion to the complexly triangulated characters. As tempers frayed and insults flew fast and loose, it became quickly apparent that fictional characters’ love lives involve significant stakes and pose wide ranging cultural significance, not only in terms of representational politics but also in terms of how producers and viewers understand their roles in unfinished serial narratives.

Known for its markedly large, racially and ethnically diverse, and gender-integrated cast of characters, Battlestar’s early episodes appeared to offer virtually limitless opportunities for fan investment in particular interpersonal relationships by allowing nearly all of its characters to meet and interact on-screen while also providing copious romantic hints and little romantic closure: a formula that can ideally facilitate fans’ interest in numerous subtextual relationships without formally validating or invalidating any of their pleasures. Thus, while certain characters spent more time together and expressed more positive and negative affect toward each other than other characters, producers could largely avoid slighting groups of fans with wide arrays of investments, including those who found pleasure in non-character-oriented story elements.6

However, producers simultaneously introduced two major plot elements that caused considerable strife. First, as the show continued, a number of initially subtextual relationships became explicitly canonized, providing fans of these pairings with evidence that the “official” version of events supported their interpretation while slighting others. Although this state of affairs and the resultant fan arguments and subsequent stridently subversive readings are hardly unusual — and the specific romantic pairings included portrayals of still contentious inter-racial relationships, both as understood by modern viewers and as understood by the quasi-futuristic inhabitants of Galactica — it is notable that a program widely hailed as genre-expanding and cutting-edge included no explicit depictions of same-sex erotics and few gender atypical couples. In other words it adhered fairly rigidly to broadly heteronormative conventions, refusing, for example, to pair older, high status women with younger, lower status men.7

Nevertheless, producers and writers followed this initial step in a fairly predictable and teleological movement toward closed heterosexual stasis with a key element of soap opera, rather than classic romance narrative. Instead of allowing the conclusion of romantic arcs in a monogamous happily ever after, they turned to a complicated series of triangulations to upset and prolong the drama of Battlestar’s romantic escapades. While nearly every romance eventually became densely triangulated, or even quadrangulated, the already vexed and overly melodramatic association between pilot buddies Kara “Starbuck” Thrace and Lee “Apollo” Adama accumulated a particularly intense network of crisscrossing passionate entanglements.

For producers, the introduction of canonical wrinkles in their established interpersonal narratives allows for a nearly infinite re-playing of the well-recognized interest evoked in a courtship plot. However, for fans who deeply involve themselves in both canonical and non-canonical relationships, rapid shifts in characters’ affections for the networks’ fairly transparent market purposes may appear to mock their own deeply passionate investments in one or another erotic outcome. Overall, such tactics complicate Battlestar Galactica’s genre-borrowing. What may at first have appeared to viewers as a fairly straightforward romance in space began to undermine the potential pleasures of romantic closure by offering an unexpected new range of potential desires.

As characters battle through endless romantic obstacles, they also dramatize latent struggles over the validity and meaning of producers’ and viewers’ beliefs, intentions, and ownership of the text. Increasingly multi-vocal, hybrid genre forms often acknowledge the heterogeneity of their audiences by combining stereotypically “male” and “female” pleasures in a single text; yet such layered structures also constantly run the risk of alienating particular devoted viewers by failing to sustain the validity of all these viewership practices simultaneously. Romantic triangles thus serve as one key location where producers and groups of fans demonstrate their influence and cultural power, infusing minute, fictional, interpersonal decisions with broad significance. While producers experiment with pursuing closer ties to fan communities and denigrated genre forms to revitalize series television in an era complicated by new media, fans concretize their own increasing importance to the emerging media landscape by asserting their equivalence with professional producers and entering into their own passionate triangulated antagonisms over the fate of the published text.

Author Bio:

Anne Kustritz recently completed a PhD at the University of Michigan, American Culture Department, and she received her BA in Cultural Studies and Psychology from the University of Minnesota. Her dissertation combined post-structuralist, public sphere, queer, and other cultural studies theory with cyberethnographic study of slash fan fiction communities. Her research interests include creative fan practices, copyright, sexuality, representation, and constructions of deviance and desire.

Image Credits:

1. A passionately antagonistic triangulation, screencap provided by author.

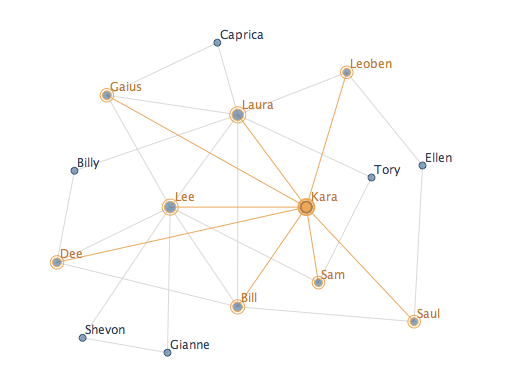

2. Battlestar Galactica’s love triangulations, interactive visualization; data set by Anne Kustritz and Julie Levin Russo.

Please feel free to comment.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men. New York: Columbia UP, 1985. [↩]

- Brooker, Will. Using the Force: Creativity, Community, and Star Wars Fans. NY: Continuum, 2002. [↩]

- Toryhoke. The Campaign for a Female Boba Fett. October 31, 2007. [↩]

- Rogers, Scott. “The Lost Fan’s Burden: Class Consciousness and the Price of Lost Fandom.” Southwest/Texas Popular Culture and American Culture Associations Conference. Albuquerque, NM, February 15, 2007. Rogers also offered a cogently argued Marxist critique of the ever higher thresholds of monetary investment necessary for full appreciation of Lost’s transmediated plot. [↩]

- Jenkins, Henry. The Magic of Back-Story: Further Reflections on the Mainstreaming of Fan Culture. December 5, 2006. Confessions of an Aca-Fan: The Official Weblog of Henry Jenkins. [↩]

- In The X-Files fandom such fans called themselves “noromos,” a designation describing their interest in program elements other than romance, including criminal case studies and/or the program’s supernatural mythology. [↩]

- While the multiplicity of human relationships portrayed on Battlestar Galactica do encompass an impressive range and complexity, they also tend to reinforce the normative position of monogamy, marriage, reproduction, and heterosexuality. The potential non-heteronormative value of the program’s canonical polyamorous relationship between two women and one man was heavily mitigated by the positioning of that relationship as the result of two female Cylons’ desire for the same human man; thus, because the human-form Cylon machines are usually coded as “the enemy,” and the relationship revolved around otherwise heterosexual women’s rivalry for a male heterosexual partner, Battlestar Galactica appeared to code lesbianism as deviant and structured by male desire. [↩]

Pingback: FlowTV | Television Conceptions: Introduction to “Re/Producing Cult TV: The Battlestar Galactica Issue”

Pingback: Graphic Engine » Blog Archive » Going with the Flow