Television Conceptions: Introduction to “Re/Producing Cult TV: The Battlestar Galactica Issue”

Last year, I was invited to become a columnist for FlowTV and to write a series of short pieces addressing current issues in television and television studies which could speak to both an “academic” and a “general” audience at once — indeed, which could challenge this very distinction between the “academic” and the “general” by acknowledging that those who regularly watch TV and those who seriously think about it are very often one and the same. This is, I would argue, just as it should be, as demonstrated by how such a multiply articulated identity (as viewer and reader, as fan and critic) is fruitfully claimed by all of the authors represented in this special issue, who deftly move among and between their personal and scholarly interests in Battlestar Galactica (2003-present) — a program that itself explores the concept of multiply articulated identities and that, in its own moves among and between stories of personal relations and scenes of political reflection, fantasy formations and critical commentary, futuristic (as well as historicist) vision and allegories for the present-day, encourages precisely the complex readings, receptivities, and identifications evident in the essays collected here. And this is not yet even to mention those who, like Battlestar Galactica star Mary McDonnell (who plays the lead role of President Laura Roslin in the program and is also a contributor to this special issue), work in television and thus also, of course, think very hard about it — again suggesting that, when it comes to television’s “reproductions,” the lines between the “general” and the “specialized” television community, the “ordinary” and the “extraordinary” TV participant (whether viewer or producer, artist, critic, or fan) are necessarily and productively blurry ones.

Not that this made it any easier for me to write my first “short column” for FlowTV. Attempting to think of a nice little topic that I could handle in a mere thousand words, I (in a moment of insanity, perhaps reminiscent of the Baltar-esque delusions of some of Battlestar Galactica‘s own characters) came up with the following: what’s the relationship between television and “personhood,” between our culture’s most pervasive medium and our notions of “being human”? Short, manageable topic, right? And even further complicated by the fact that I tried to address both television viewing and television programs, ranging over considerations of what it means to watch TV, alone or with others (and thus, what sorts of “selves,” “families,” and communities television might yield), as well as over considerations of what various television texts themselves — with Battlestar Galactica as a prime example — might indicate about the possibilities and/or limitations of “personhood,” the “human self,” “family,” and community. Probably needless to say, I couldn’t, in the requested length, quite do justice to the complexity of the topic—and to the complex and multivalent way in which Battlestar Galactica itself handles these issues.

This complexity emerges from what might, at first glance, appear to be a commonplace science fiction trope: Battlestar Galactica traces the after-effects of an apocalyptic nuclear attack on human civilization by cyborg beings, initially built to “serve man” as machines and/or slaves. Yet these familiar scenarios are defamiliarized by the very ways in which Battlestar Galactica regenerates and re-imagines previous images of generated automata (not to mention pressing real-world concerns about war and biopolitics). The premise of the program is deceptively simple, encapsulated in the show’s first season title sequence:

- The Cylons were created by Man.

They Rebelled.

They Evolved.

They Look and Feel Human.

Some are programmed to think they are Human.

There are many copies.

And they have a Plan.

A “Plan,” though with some unexpected debate among the Cylons, to wipe out the vestiges of the human population (now on the run, in search of “a mythical planet called Earth”). This agenda must therefore be resisted and foiled by President Roslin and military commander Admiral Adama (Edward James Olmos), along with the crew of Galactica and an assorted fleet of civilian ships under their leadership, through a counter-plan to save the survivors and ensure the continuation of humankind, thus requiring the maintenance and renewal both of the populace and of “human culture” as a whole.

As even just this premise indicates, Battlestar Galactica is all about reproduction — technical, textual, familial, even “universal” — from the generation of babies, to the regeneration of equipment, to the replication of Cylons (in addition to the creation of assorted “hybrids”), all the way to the very “delivery” of humanity… or maybe more accurately, as hinted at in the notion of hybridity, an expanded conception of what we might call “humanity plus.” Yet as that “plus” indicates, this is not reproduction in the sense of simply duplicating the same; rather, there is reproduction with a difference — that is, a re-visioned, re-envisioned production — at every level of the program and its own creation, re-creation, and propagation.

It is this dynamic that we are attempting to evoke with our title for this issue, “Re/Producing Cult TV.” Clearly, as I’ve indicated, “reproduction” is a narrative theme across the program. But beyond Battlestar‘s stories of what we might see as literal reproduction — the birth of children, cyborgs, civilizations — there are stories that involve a more figural reproduction, that disrupt the boundary between the literal and the figural, that, indeed, re-produce (and, in so doing, incite us to re-view) our own stories, histories, and possible futures. Many of the program’s plots have complex allegorical dimensions, alluding to issues and events as varied as, for example, Nazi genocidal politics and WWII resistance efforts (as well as more recent “final solution” or “ethnic cleansing” policies in places like Cambodia, East Timor, Bosnia, Rwanda, Darfur); guerilla warfare, as reminiscent of Vietnam (not to mention the present-day Iraqi insurgency); the threat of infectious diseases, viral epidemics, and biological warfare, as feared today; political and religious conflicts, with their attending conflicting meanings of terms like “terrorism,” “counter-terrorism,” and “suicide bombings,” as devastatingly evident in the clashes in the Middle East; timely debates about the detention and torture of “unlawful combatants”; the possibility of election fraud, with its real-life corollary being, I trust, obvious — indeed, I would suggest that, though assumed by some to be “merely” a trivial fictional program in a campy cult genre, Battlestar Galactica offers the most serious and sustained (and never cut-and-dried) examination on television of life in a “post-9/11” world.

In its televisual reflections of our world, Battlestar Galactica does not often look at TV itself… with the exception of the diegetic communications network “the wireless,” highlighted in an intriguing episode (“Final Cut,” 9/9/05) in which a Cylon, posing as a human, produces a documentary about life aboard Galactica — a “machine-subject” (a cyborg) deploying another “machine-subject” (video) to construct a way of viewing and re-viewing humanity. But, even beyond this, in its very operations, Battlestar Galactica embodies how television itself functions as a technology of production and reproduction, generating knowledges of our world through the “labor” of everyone and everything involved in TV: media institutions (which, of course, produce not only programs, but textual norms, social discourses, demographic categories, tie-in commodities, and consumer desires), industry workers (with the complex dynamics of multiple authorship that a medium like television necessarily entails among executives, writers, producers, directors, actors, and crew); and television viewers, investing meanings and desires in what they see.

The current Battlestar Galactica is itself a televisual reproduction of an earlier series, a program that aired in 1978-79 and that has since become a cult camp classic (despite, or because of, its own tangled history of replication, pointing toward the complicated relations and reproductions that also link media, political, and legal discourses—for instance, the questions of “intellectual property” that played out in battles with the first series over charges, eventually dropped, of copyright infringement). Later, after several failed attempts to revive the program in the intervening years, the Sci-Fi Channel (with Ronald D. Moore as creative force and co-executive producer) finally brought the re-imagined series to fruition in 2003, with first a mini-series and then an on-going weekly serial (now on hiatus until its fourth and final season premieres in April).1 In turn, one might say that Battlestar Galactica brought the Sci-Fi Channel fully to fruition—a case study in the shift in the television industry from “broadcasting” to “narrowcasting,” as well as in the “convergence” of television and so-called “new” media technologies (such as the internet), in that this fictional drama, with its own explosive premise, both relied on and furthered the explosion of channels in the “cable revolution” and the explosion of outlets, audiences, authors, and textual and product tie-ins in the “digital revolution.” With “cult television” now conceived by the industry as a viable economic strategy and, alternatively, by groups of viewers as a particular relationship to animating and re-animating TV, the scene was set for the emergence (or re-emergence) of the complex phenomenon and textual constellation known as Battlestar Galactica.

This phenomenon also, of course, involves a constellation of people, all involved in creative work even as they are simultaneously (and necessarily) enmeshed in commodity culture — the two of which, as television has taught us, cannot be seen as oppositions. While it is no doubt true that the television industry defines “personhood” and “human identity” in consumer capitalist terms (selling audiences to advertisers and offering a “demographic” rather than “democratic” vision), this perspective does not exhaust the implications and operations of television and television viewing. Indeed, viewing itself can be seen as re-production with a difference — as both pleasure and labor, proliferating and propagating meanings, affects, identities, relations, and communities in multiple ways (some, arguably, disempowering; others perhaps quite empowering, albeit within certain limits). This is particularly evident with the fan communities that are so active in their viewing and re-viewing, identifications and appropriations of cult texts like Battlestar Galactica. Producing an amazing range of creative material — fan fiction, art, films, and videos; podcasts, blogs, archives, and wikis; public events and private reflections — these viewers claim their own authorship over television, challenging notions of fixed hierarchy, authority, property, and propriety through their varied practices and actualizations. Again, this is especially evident with self-identified fans; but I would argue, as many other TV scholars have argued, that all viewing works this way (or can and should work this way): not simply as a means of consumption, but as a means of production that challenges, then, that very production / consumption divide, along with other such divides like education versus entertainment or critical versus popular response.

Our objective in putting together this issue of FlowTV was to encourage and embody exactly this boundary crossing, this intermixture and hybridity. The contributors include people who labor at television (re)production from both sides of the screen: Mary McDonnell, who is, of course, centrally involved in creating the show, and myself, Melanie Kohnen, David Bering-Porter, Sarah Toton, Julie Levin Russo, Alanna Thain, Anne Kustritz, and Bob Rehak, all of whom are involved in re-creating it in our work as spectators, enthusiasts, and academics. But, in our multiple roles, we might all be seen as all of the above: viewers, producers, artists, critics, and fans. Our hope is that, through the mutual dialogue that is the goal of this special issue (and of FlowTV as a whole), the multiple roles that all of us play in our relationships to television, culture, critique, and “personhood” will also be further animated, amplified, and propagated — that is, will also be “re-produced.”

Author Bio:

Lynne Joyrich is an Associate Professor in the Department of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University. A member of the Camera Obscura editorial collective, she is the author of Re-viewing Reception: Television, Gender, and Postmodern Culture (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1996) and of a number of articles and book chapters on film, television, feminist, queer, and cultural studies in various anthologies and journals.

Issue Credits:

Lynne Joyrich, Guest Editor, “Re/Producing Cult TV: The Battlestar Galactica Issue”

Julie Levin Russo, Guest Associate Editor, “Re/Producing Cult TV: The Battlestar Galactica Issue”

Jean Anne Lauer, FlowTV Editorial Liaison, “Re/Producing Cult TV: The Battlestar Galactica Issue”

Image Credits:

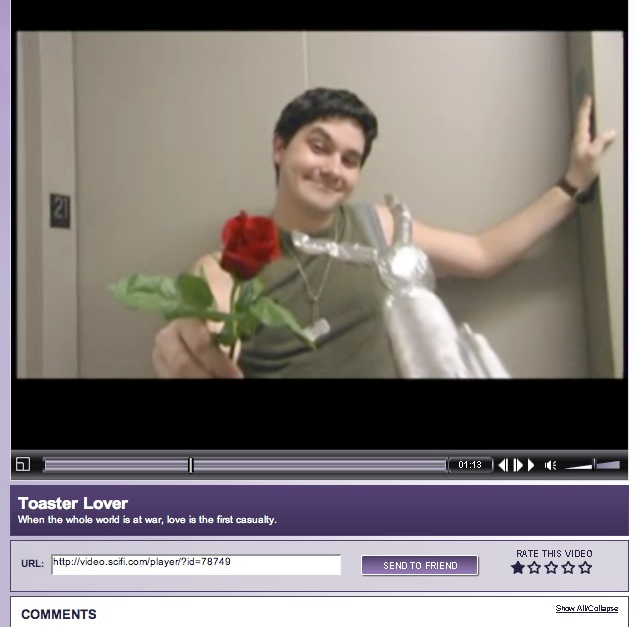

1. SciFi promo of Battlestar Galactica

2. Images and captions from the title sequence (season 3), screencap provided by author.

3. A prophetic vision of the first Cylon-human hybrid baby, ibid.

4. Scenes from the occupation of New Caprica, ibid.

5. Reporter (and Cylon) D’Anna Biers films Lt. Gaeta in the episode “Final Cut,” ibid.

6. An entry in the SciFi.com fan film contest Videomaker Toolkit, ibid.

Please feel free to comment.

- The Sci-Fi Channel is the U.S. home of Battlestar Galactica; in the U.K. and Ireland, the series airs on Sky One. [↩]

Although I have never watched Battlestar Galactica, the way in which you describe its complexities and themes, makes it sound like a show worth watching. It is interesting how the show alludes to political and bio-ethical issues of today, as well as past events such as world war two and the post Nazi/Cold War era. Not to mention it has a great story line, one unlike any others I have seen before. The shows plot, humanities struggle against a robot race that evolved, initially made by humans, parallels with genocides going on today. Like you said it is a good example of what we are going through globally in the present.

Another good aspect of your article is how it touches on fandom. I always knew there was a cult following for Star Trek but never had a clue about Battlestar Galactica. Much like Trekkies, Battlestar followers are creating communities and websites which serve as outlets for new creative developments such as those made through Star Trek communities; for example new stories and ideas branched off of the original plot, such as the Kirk and Spoc sexual tension on the show. Just like Battlestar, Star Trek gave birth to a huge cult following, also creating fan short films, web episodes, blogs, and other types of visual art. And just like Battlestar fans, Trekkies also claim ownership to their ideas and innovations. This brings up the question, is television a spectator pastime? At what point does the spectator become so immersed in television that he or she feels the need to produce their own works as tribute to something he or she has seen on the TV.

I think it is very interesting how, TV and media have gone hand in hand with consumerism for so long. Now come along shows like Star Trek, Battlestar, and really any show that enthralls an individual, which beckon people to produce works of their own. Today however it is much easier to give tribute to a show because of technological advances such as more people are computer literate and are able to write programs, create videos and put together web pages. This makes shows today more prone, in my opinion, to have cult followings. Really any one can go online these days and go to youtube.com and see a tribute video to any show they like. The advent of youtube.com in particular, I think, has helped fandom and fan participation in fan cults to explode and reach more and more people world wide.