Automated for the People

Gerald Sim / Florida Atlantic University

Last May, when OpenAI withdrew Sky, the ChatGPT voice that resembled Scarlett Johansson’s too much for the actress’s liking, the startup learned a lesson that Disney had paid for 3 years before. Unhappy with negotiations over her lost earnings when the studio released Black Widow in theaters and on Disney+ simultaneously, she sued and later settled for breach of contract. After shrugging off the axiom that you “don’t mess with the mouse,” she had now chastened OpenAI.

While Scarjo possesses an uncommon level of industry power, the Microsoft-backed startup’s reluctant retreat says a lot about tech companies’ depreciative view of creative labor. Johansson’s account of her unseemly negotiations with CEO Sam Altman and OpenAI’s rush to release Sky underlines what artists can expect of the threat they face from a tech industry that prefers to apologize rather than seek permission.

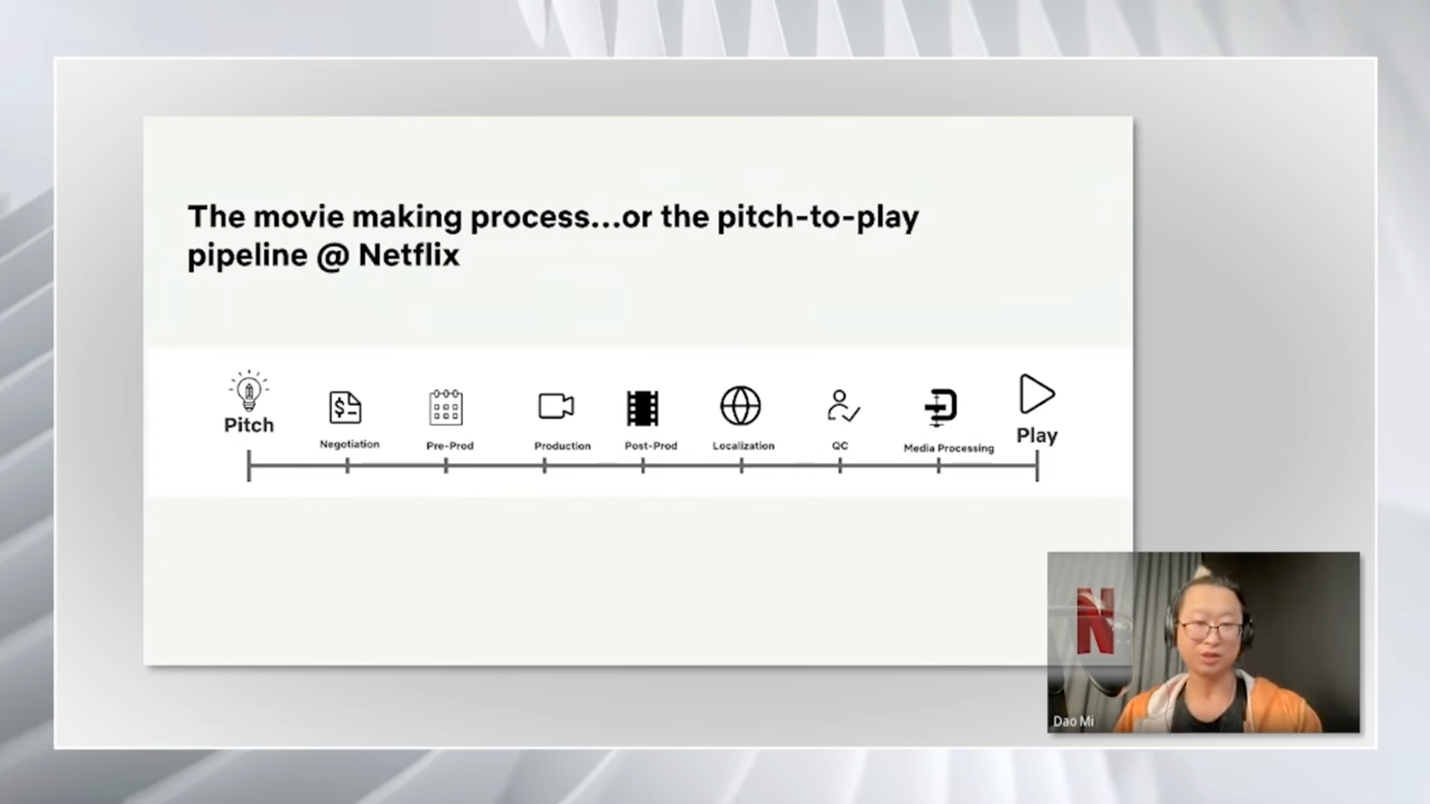

The push to automate creative work continues apace—sometimes less brashly and behind the technological determinist’s alibi. Machine learning systems are sold as tools to augment, empower, or enhance human creativity, with a promise that the artists will remain central. Indeed, these buzzwords pepper Netflix’s slate of media-focused machine learning research that began appearing on its blog in 2022. The goal to bring “science and art together to revolutionize how content is made” followed its concerted move into production; Netflix Originals now constitute most of its content library.

Netflix TechBlog inaugurated the “Creating Media with Machine Learning” series with a tool to help film editors create match cuts between shots of similar graphic compositions. The entry is cross-promoted by a slick video (below) embedded from a sister YouTube channel and hyperlinked to a IEEE/Computer Vision Foundation conference paper. Together, they show off a system that can process a large amount of film footage, identify shots with comparable compositions and movements, and rank the 50 best candidates for match cuts.

The model’s proof of concept was verified by Netflix’s in-house trailer editors, who are responsible for generating multiple versions to bolster its personalized audience experience. For those who create what Netflix calls “promotional media assets,” the system makes complete sense. But in promoting the shot-pairing tool, the TechBlog and scientific paper proffer its value to film and television editors above the rest.

Match cuts, the authors explain, are elegant and efficient storytelling tools that transition between scenes set in different times and places. They provide contextual information quickly and create emotional bonds between characters. The point is illustrated with exemplars from feature films, namely Forrest Gump, Disney’s Up, Park Chan Wook’s Oldboy, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and that “Intro to Film” mainstay, the bone-toss-to-space-station cut from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Only after, directly below the GIF from Kubrick’s film, does the TechBlog mention trailer editing: “[m]atch cutting is also widely used outside of film. They can be found in trailers.” (emphasis mine)

The primary focus on feature work is telling. If the system were being pushed to trailer editors, match cuts would be described as a way to create visual impact. Instead, they are presented as complex storytelling devices that connect scenes and provide backstory. In Kubrick’s hands, the paper’s authors posit that the technique was “a highly artistic edit which suggests that mankind’s evolution from primates to space technology is natural and inevitable.”

Except, would any film editor ask for this tool? None of the editors who assembled the graphic matches lauded by the machine learning engineers and “creative technologists” at Netflix would have, and not because they’re stodgy purists resistant to innovation. Film editing made the digital transition swiftly during the 1990s. Rather, the tool is simply incongruent with how graphic matches are made. Match cuts are not conceived by editors alone. The more metaphorical and meaningful the edit, the more likely it is that the idea was hatched long before post-production. Matches are planned, storyboarded, blocked, and shot accordingly. Save for a filmmaker like Wes Anderson whose compositions are obsessively uniform, editors typically can’t decide after shooting has wrapped that they want a match cut. They certainly don’t need the ranked list of best shot pairings that the Netflix system generates.

Did a film editor have input into its construction? When the engineers decided to filter out matches between “the face of one character to the back of another” because those were considered “false positives,” a film editor might have pointed out that such matches could in fact be quite useful because graphic matches are often not identical.

When showcasing the “Creating Media with Machine Learning” series, Netflix engineers talk about bringing “science and art together to revolutionize how content is made.” For the moment, most of their applications only aid the management work of producers to streamline logistics, optimize media workflows, and make audience projections. The match cutting system would affect the final product on screen most directly, however. This is significant because of the huge affordances for AI mission creep from project planning to artistic creation.

On the “Match Cutting at Netflix” video, one engineer reassures creatives: “We’re their friends, we’re trying to give them better tooling so that Netflix has a whole can make better shows, better trailers, and better videos for the whole world to enjoy.” To those who edit film and television, not just trailers, another engineer underscores that they are not conspiring to replace or interfere with creative workers, only building tools that let “creatives focus on the more creative aspects of their job.” A trailer editor and “creative technologist” then chimes in about how Netflix presides over a happy marriage between science and art: “The engineers here understand how valuable creativity is and then the creatives here also understand the value that tech can bring to this space.”

We hear this augmentationist rhetoric a lot, not just from Netflix. [1] It’s human-centered AI, they’ll say, implicitly hat-tipping Douglas Engelbart at every turn. Netflix has a particular interest in protecting its reputation as an artistic oasis that dispenses only money and not interference. Showrunners like Shonda Rhimes (Bridgerton) and Beau Willimon (House of Cards) have effused publicly about the creative freedom they enjoyed with the company.

Big names in the Netflix stable don’t have to worry. The potential market of early adopters won’t include A-Listers with any kind of clout. Who would’ve volunteered to ask Martin Scorsese and his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker if they’d like to use an exciting new AI tool for The Irishman? But the hard sell could go to independent artists on starvation budgets and series producers in developing markets. If that happens, how long will it be before content starts to look like trailers, before match cuts wither into postmodern pastiche? European producers, writers, and showrunners working for Netflix are already being pushed to write, frame, and light scenes for smartphone viewing by subscribers whom the streamer expects to be texting at the same time.[2]

These crew members live a world apart from Scarjo, but now find themselves on the frontlines of a common battle that has been brought to their door. In the foreseeable future, the infatuation with AI systems at the top of media industries will fuel the drive to devalue creative labor and extract surplus value. And the failed attempt to steamroll Johansson may not represent the upper limit of their audacity. All the more reason to be wary of affable overtures to help “creatives focus on the more creative aspects of their job,” given the apparent indifference towards what prospective users need, want, or actually do.

Under different circumstances, these AI tools could better bridge art and technology if made more accessible. The match cutting system would be invaluable to found footage collage artists, for example, who may otherwise crowdsource the image search on social media.[3] They’d bring no financial upside, though. Without a way to monetize, let alone scale, the idea is a non-starter. But can we imagine it? Perhaps a trailer…

“In a world… where artists and scientists are free from the demands of capital… and AI is owned by all… in their hands, technology is a font of beauty and good.”

Image Credits:

- Photo by Wahid Khene on Unsplash.

- “Match Cutting at Netflix” 2022.

- Screenshot of Figure 1 from Boris Chen, Amir Ziai, Rebecca S. Tucker, Yuchen Xie, “Match Cutting: Finding Cuts with Smooth Visual Transitions,” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (2023): 2115-2125.

- Screenshot from “Netflix Data Engineering Tech Talks – Media Data for ML Studio Creative Production” 2023

- “Feeling Every Shot: Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE on Editing The Irishman” 2019

- Entertainment industry-focused AI companies Largo and Cinelytic, which make financial forecasts, offer reassurances that their services are “designed to empower traditional content creation” (Largo). [↩]

- Daphne Rena Idiz, “Local Production for Global Streamers: How Netflix Shapes European Production Cultures,” International Journal of Communication 18 (2024): 2129-2148. [↩]

- See the exceptional work of filmmaker Jennifer Proctor. [↩]

Great article! Cinema is going to change a lot of engineers are at the helm!

The irony of that, Jon… is that of the students who get A’s in Intro to Film, half are engineering majors. [upside down smiley face]