And You Love The Game: Stream-Pop as a Never-Ending Scavenger Hunt

Eric Harvey / Grand Valley State University

“I think that it is perfectly reasonable for people to be normal music fans and to have a normal relationship to music. But…if you want to go down a rabbit hole with us, come along.” – Taylor Swift to Jimmy Fallon, November 2022

“Rabbit hole is still deep, I can go further, I promise.” – Kendrick Lamar on “Not Like Us,” May 2024

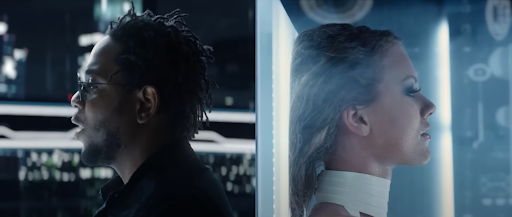

In an interview before the release of her blockbuster 2014 album 1989, Taylor Swift explained that the song “Bad Blood” was directed not toward a former romantic interest, but another female pop star who’d crossed a line in her business dealings with Swift. The next day, Katy Perry obliquely confirmed the rumors with a lightly coded Mean Girls tweet. Fittingly for an intra-industry diss track, when it was time to release “Blood” as a remixed single, Swift brought along Kendrick Lamar, whose own 2015 single “King Kunta,” released a few weeks before “Blood,” took anonymous aim at fellow rappers who were rumored to use ghostwriters. Later that summer, when hardhead Philly rapper Meek Mill assailed Drake on Twitter for that very crime, fans had the answer they already knew. Swift and Lamar haven’t collaborated again since, but almost a decade later, they’re more famous than ever, and still planting clues.

Even when mysterious, “gamified” social media album promo is the norm, Swift’s cryptographic intimacy with her avid fanbase is unparalleled. The same fans who are showing up for Swift’s world-conquering Eras Tour dressed as lyrical deep-cuts are poring over TikTok and Instagram, trying to ascertain what each show’s “surprise” songs or “Taylor’s Version” re-release announcement will be. Swift has been hiding messages in her liner notes as long as she’s been releasing albums, ranging from the title of her favorite Tim McGraw song to the phrase “MAPLE LATTES” in the “All Too Well” lyric sheet, which a Google search revealed a paparazzi photo of Swift with actor Jake Gyllenhaal. From Lover onward, Swift’s star image-as-NYT Games App approach went into overdrive. After Swifties found the title in the video for “ME!,” that album cycle’s deliberately queer-tinted iconography convinced one Times columnist to spend five thousand words speculating about Swift’s own sexuality. Though Swift demurred on that question, she later confessed to hiding a “psychotic amount” of clues in the Midnights single “Bejeweled,” announced the bonus tracks for the Fearless reissue by challenging fans (level: Expert) to decode the song titles in a Twitter video, and co-created word games with TikTok and Google for The Tortured Poets Department. It all appeals to the Spelling Bee fan in me, even if the revelations most often boil down to the 2024 pop star equivalent of “be sure to drink your Ovaltine.”

As a lifelong rap fan who enjoys Swift’s music quite a bit, I can’t help but note the commonalities between her scavenger hunts and the website Genius.com, where anyone can earn “points” for contributing “explanations” for song lyrics. I wrote about Genius 11 years ago, when it was known as Rap Genius and was collecting millions in VC funding by turning hip hop lyric exegesis into a Google-baiting quiz—each bar from a given song received its own unique URL, no matter how trifling or condescending the “explanation” was. Genius has since expanded its ambit to all pop lyrics, but rap fans remain its primary contributors, and they were especially frantic from late March through mid-May of 2024, after Kendrick Lamar sparked a rapid-fire, densely referential, and undeniably dark war of words with Drake. For a few weeks, as the rappers lobbed bombs at one another on YouTube, Spotify, and even Instagram, every word was a code to be cracked: Drake’s “drop and give me fifty” from “Push-Ups” was a simple double-entendre, but Lamar’s use of the word “Hellcat” in the followup “Euphoria” generated paragraphs of analysis. Wait, is that an Ozempic bottle on the original cover art for “Meet the Grahams?” Explaining his “unhealthy obsession” with the beef, blogger and diehard Lamar fan Yousef Srour self-effacingly cited an embarrassing offline conversation starter he tried to use in the fog of war: “Did you know that Drake was supposedly in L.A. with 16 year-old Bella Harris on June 16th, 2016 and that’s why Kendrick named one of his diss tracks, ‘6:16 in L.A.?’”

Though rap has long been translated by its fans and critics into rankings and lists—this beef kicked off with Lamar denying that he was part of the “Big Three” that J. Cole outlined on a 2023 Drake single—this one felt especially thorny. “As a fan of puzzles and brain teasers, these (Kendrick) diss songs feel like the ultimate challenge,” wrote Srour. Not everyone was so entranced. Music reporter Joe Coscarelli wryly opined that “all of rap fandom has become the True Detective Reddit from season 1.” Veteran hip hop commentator Jay Smooth issued a video from a self-described “Old Head” perspective, exhaustedly noting that, “in order to make sense of the beef, we’ve got to analyze this whole Pepe Sylvia corkboard and figure out what we actually think is true or not.” Smooth added that Drake ostensibly revealing Lamar’s domestic abuse, and Lamar striking back with accusations of Drake’s dalliances with underage fans felt less like a traditional rap beef than a political oppo dump leading up to an election. The young critic Alphonse Pierre was among the haters: “Go on Twitter or Instagram or TikTok or YouTube where the beef is being followed like it’s Game 7 of the NBA Finals meets a gladiator duel,” Pierre wrote. “They both sound mostly like bitter, lonely rappers having a misery-off.” Everyone agreed that Lamar “won,” whatever that meant, but for all of the beef’s only-in-2024 elements, two rap titans battling for lyrical supremacy also felt antiquated—or, in Pierre’s words, “the death knell of a dying era.” If that’s true, then what do we call the era we’re in now?

As a music critic and scholar of pop music, I’m well aware that the musical traditions from which Swift and Lamar draw—singer-songwriter pop and lyric-centric hip hop—incentivize a biographical type of lyrical interpretation. The rock era is rife with such conspiratorial treasure hunts, from John Lennon singing “here’s another clue for you all, the Walrus is Paul,” to ‘70s suburban stoners decoding Led Zeppelin sleeve arcana for hints to the band’s occult leanings, to self-proclaimed “Dylanologist” A.J. Weberman getting punched by Bob Dylan after getting caught digging through the folk icon’s trash. It’s Swift’s lyrical hero Carly Simon extending the “who’s the subject of ‘You’re So Vain’” game for decades, dropping a backmasked hint as recently as 2009, on an album whose cover positions Simon herself as a detective. More recently, it’s Nine Inch Nails overlord Trent Reznor encoding an entry ticket to the vast sci-fi narrative universe behind his 2005 album With Teeth in the randomly capitalized letters on the back of a concert t-shirt. And it’s the entirety of hip hop’s existence, which ushered hyper-referential wordplay, too-clever samples and internecine battles with fellow practitioners into pop’s lingua franca.

But as one of a handful of pop music scholars at media studies conferences and a small number of media studies folks at pop conferences, I’m constantly asserting to my peers that it’s impossible to understand 21st century music without accounting for the digital media interfaces through which it circulates. The record industry first ceded control of its digital commodities to Apple in the early 2000s, and has since gradually permitted the ideology of Silicon Valley to redefine musicking in the image of what Alexander Galloway calls “ludic capitalism.” For Galloway, the 21st century app developer or VC-funded social media baron is “the consummate poet-designer, forever coaxing new value out of raw, systemic interactions,” such that “labor itself is now play, just as play becomes more and more laborious.” Since the early 2010s, this ideal has created a relatively stable assemblage–one that, for lack of a better term, I’ve been calling The Stream: the ceaseless flow of music and discourse about music through surveilled platforms (Spotify, YouTube, TikTok, Twitter, Instagram, Soundcloud, Discord, etc.), accessed through smartphones and laptops, anytime and anywhere.

Scholars, critics, and fans tend to think about these platforms in isolation from one another, which is analytically useful, but stops short of revealing how much social media and music streaming platforms work together to facilitate the acceleration of music discourse and transformation of music fandom into a reflection of the tech-world’s obsession with metrics, Wiki-able explanations for everything, and 24/7 “engagement.” We’ve exhausted discussion of “the algorithm,” a synecdoche for everything we don’t know about how music gets to our ears in the streaming age. But with a couple important differences, black-boxed systems of data gathering and analysis have been governing the generation of radio playlists for multiple generations. What I find far more interesting and vexing are new cultural practices afforded by The Stream that are right there for all to see.

For instance, it makes my teeth itch to see song lyrics so frequently reduced to clues, as if each word in a song–even rap jibberish devised to fit a cadence–will reveal its true meaning if only we search hard enough. And apart from stars sicking stan armies on their critics, is it healthy for our music ecosystem to devote so much time to publicly decoding a star’s sexuality, or–in the case of Lamar and Drake respectively–determining whether or not they have committed domestic violence and/or sex crimes? “Back in the days, we really didn’t know much about any of these rappers beyond what we heard in the music,” Jay Smooth explains in his video. “But in this social media era that’s defined by everyone knowing way too much about everybody–or feeling like they do–rap beef has been shifting more and more from low-stakes shit-talking into this whole elaborate propaganda war.” Richard Dyer explained that the construction and interpretation of stardom is rooted in the “really” question. “It is the insistent question of ‘really’ that draws us in, keeping us on the go from one aspect to another,” Dyer wrote. Experiencing music stardom in the Stream affords more people than ever before the capacity to stay “on the go” in their search for truth, coupled with the belief that the internet itself holds all the answers. Where else would they be?

As Swift notes in this essay’s first epigraph, millions of people still enjoy pop music on its merits, without following the stars down their intricately constructed rabbit holes. But the all-consuming nature of music fandom in the Stream increasingly reminds me of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Critic Sam Adler-Bell recently interrogated how MCU kingpin Kevin Feige “managed to recruit fans of the MCU into rooting not merely for its superheroes, but for his own business plan,” by spending hours online dissecting “the twists and turns of Feige’s content development pipeline, which is divided into numbered ‘phases,’ as they would be on a corporate slide deck.” Quite often, they reify casting decisions and marketing strategies as the essence of criticism, not unlike many Swifties paying homage to boardroom decisions as the sine qua non of pop creativity.

thank you @pitchfork for your kind words.

— h (@halsey) October 30, 2024

I think it’s so beautiful that everyone interprets things differently 🤍⭐️ pic.twitter.com/AwAZCBNEyC

To the capitalist class building apps and platforms–and many thin-skinned superstars themselves–the laborious play of The Stream obviates the need for informed, independent music criticism. A thousand words or so of analysis juts awkwardly out of the frictionless Stream, and over the past decade, I’ve watched dozens of talented friends and colleagues laid off en masse over the past decade in favor of clickable “content.” While no era of the global recording industry has ever been innocent of alienation, extraction, and exclusion, and the joy enabled by music fandom is undeniably true, I do fret about the implications of music’s current assemblage, when so many listeners seem to equate lyrics with evidence, and stardom as a series of puzzles to solve, without having the option to eavesdrop on expert conversations in pop’s public sphere. So while I’m going to obsess over anything new that Swift or Lamar releases, it increasingly feels like an ironic statement of purpose in the era of pop scavenger hunts to assert that I’ll proudly do so cluelessly.

Image Credits:

- Kendrick Lamar and Taylor Swift in video for “Bad Blood.” (screenshot: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QcIy9NiNbmo)

- Genius allows users to “explain” the meaning of song lyrics. (screenshot: https://genius.com/artists/Kendrick-lamar)

- Veteran hip hop commentator Jay Smooth explains why old heads hated the Kendirck vs. Drake beef.

- Halsey thinks it’s beautiful that everyone interprets things differently.