Extreme Weather as Everyday Genre in Subway Flood Videos

Juan Llamas-Rodriguez / University of Pennsylvania

“New York seems to have decided that the floods won,” regretfully writes Clio Chang in a Curbed article about how the storm-induced floods of summer 2022 echoed those caused by hurricanes throughout 2021. As the lack of cooperation between city and state government officials results in slower, more ineffective responses to the infrastructural woes of the subways, Chang worries that people will become accustomed to the continuous flooding and treat it as an unremarkable experience. “The spectacle used to feel shocking; now it’s more of a genre.”

The mediated depiction of extreme weather events and their impacts on urban areas has always tended towards the spectacular. As Julia Leyda and Diane Negra argue (2015: 24), “What we have come to expect of weather media is a particular kind of sensationalist and myopic coverage.” In Sustainable Media (2016), Janet Walker and Nicole Starosielski warn it is the duty of critical media studies to complicate and destabilize this narrow focus on the spectacularization of environmental catastrophe.

What if we took Chang’s diagnosis about the shift from spectacle to genre seriously? I propose that subway floods are emerging as a genre for everyday life, one that simultaneously manages expectations about how extreme weather events will cause ordinary crises and exposes the disintegration of the infrastructure (both social and physical) that would be equipped to deal with such crises. “Genres present an affective expectation of watching something unfold,” according to Lauren Berlant (2011). Ordinary psychic, emotional, and interpersonal dynamics take the form of genres and genre conventions. Our hopes, understandings, and interactions take shape in conventional aesthetic and narrative storytelling forms. If subway floods emerge as an everyday genre, subway flood videos, in turn, are the texts that allow us to trace the structure of feeling of this social genre.

For some users, these videos function as a way to channel frustration with an everyday inconvenience through the mixture of fact, affect, and pop culture commentary. In a series of videos about people struggling to get into the subway station after it has been flooded, the despair and frustration at this real-life problem gets remediated into humorous clips and satirical takes. TikTok users, for instance, make use of the platform’s sounds to ironically comment on the state of their city: one video adds the sad music theme from SpongeBob Squarepants; another adds “Empire State of Mind” over a video of a waterfall coming through the exit on the 20th St station. Within the comment sections of the videos, users also make references to popular media spectacles that remind them of these subway floods, namely the sinking scenes in Titanic or Universal Studios “Earthquake!” ride.

@gamergirl_0298 #stitch with @gl00mie_ ♬ Empire State of Mind (Part II) Broken Down – Alicia Keys

If, as Brian Larkin (2013) argues, infrastructures “encode the dreams of societies” in such a way that social ideals can be “transmitted and made emotionally real,” and, as Alicia Keys reminds us, New York is the “concrete jungle where dreams are made of,” then these subway videos transmit and make emotionally real the dreams-cum-nightmares of infrastructural disrepair in the face of increasingly more extreme weather.

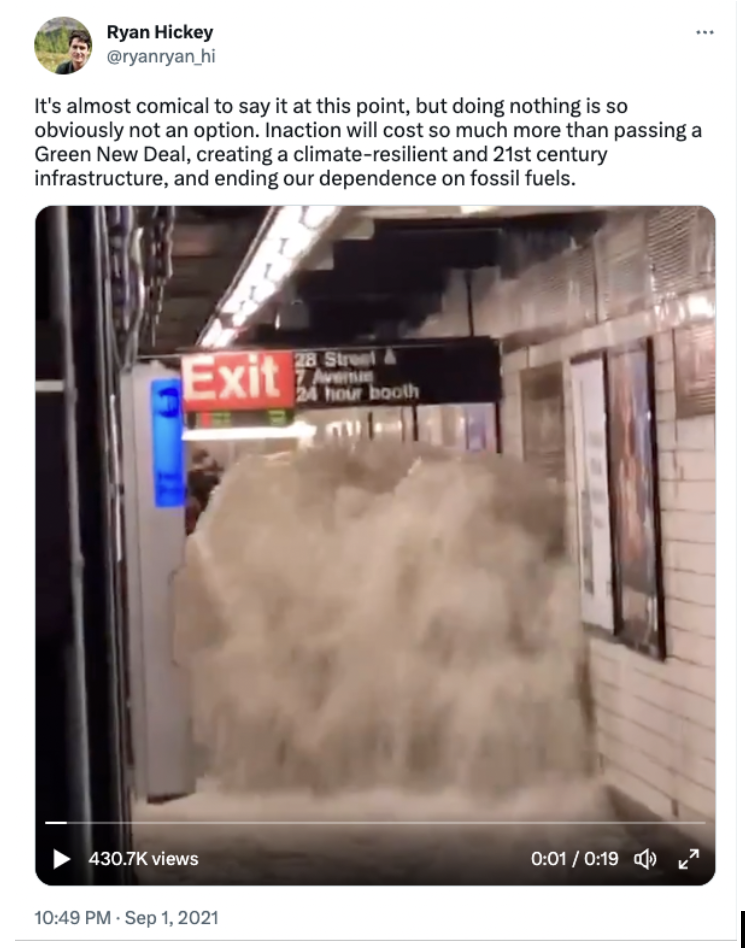

For other users, subway flood videos act as a heuristic, a shortcut that renders a complex phenomenon in such a way that an audience can comprehend it all at once. These videos allow the viewer to visualize cause and effect: the subway infrastructure breaks because of the pressures of the extreme weather event, but this event is not merely implied or gestured at. It explicitly appears in the frame as a reminder of the aboveground conditions creeping into the underground. This theater of proof offers an avenue to link the increase in extreme weather events not only to planetary climate change but also to the infrastructural disinvestment and disrepair:

By now, the adage that infrastructure remains invisible until it breaks down seems well-worn. But if the “environment is the infrastructure of infrastructure,” as Kregg Hetherington proposes (2019), then the breakdown of subway infrastructure as a result of extreme weather events offers a double instantiation of what Geoffrey Bowker (1994) calls “infrastructural inversion,” bringing the background to the foreground. Subway flood videos foreground not only the taken-for-granted transportation infrastructure as it fissures and breaks but also the taken-for-granted environmental conditions as they intensify and worsen.

The framing of subway flood videos — how they present the linkage between extreme weather events and infrastructural disrepair — remains inextricable from the video’s framing — their aesthetic presentation. Because they are recorded on users’ phones in the moment, most subway flood videos rely on the vertical frame of the smartphone. Viewing vertical videos in the intimate setting of the handheld smartphone forces us to see how these images can be personally paused, interrupted, rewound, and infinitely rewatched in a seamless fashion. Media marketers and scholars alike propose that vertical moving images watched on a mobile device can potentially provide significant immersive experiences of intimacy and allow a unique personal connection between technology, media text, and audience.

Yet the smartphone aesthetic is significant not only because its vertical frame offers a subjective, individualized pov. Instead, I propose to think through this unique and immersive connection somewhat tangentially by drawing on Amy Rust’s theorization of the ecological aesthetic of Steadicam. For Rust (2016), the perspective offered by the Steadicam forgoes the shakiness of handheld without reverting to the stability of the dolly, resulting in a paradoxical stance: “Ungrounded yet unwavering, the device’s unencumbered stability lends images limited, even unstable, force.” The Steadicam’s ungrounded yet unwavering perspective locates and dislocates viewers, removing and returning them from and to what remain linked but distinct possibilities. The ecological aesthetic of this technology lies in its ability to present viewers with “omniscience and subjectivity as simultaneous yet nonidentical experiences.” Relying on vernacular literacies about framing, timing, and self-referentiality, some subway flood videos likewise manage to gesture at these ambiguous identifications, this oscillation between omniscience and subjectivity:

The ubiquity of smartphone-generated videos accustoms us as audiences to think of them not only as subjective recordings but also as openings into the everyday world as experienced through a mobile device. Especially when filming an event that is both visually arresting and significant to others besides the individual filming it, the subjective point of view of the vertical video opens up into the omniscient perspective of watching an entire urban infrastructural collapse.

These videos could thus offer us an ecological ethic for our times: a way of relating to, thinking through, and responding to the impending environmental collapse in front of us as evidenced by the infrastructural disrepair that structures everyday commutes. The continuous confrontation with an unfolding crisis that is both individually frustrating and collectively debilitating forces viewers to oscillate between perspectives and subject positions. For Rust, the merging of primary and secondary identifications offers an ecological ethic that brings freedom and responsibility together: “Demanding that spectators tarry with worlds that, in turn, restrict them, the device joins private interest to public imperative and opens perdurance to possibilities for change.”

Chang concludes her 2022 Curbed article by noting that the NYC government claims everyone has a role to play in dealing with subway floods. “That role,” Chang concludes, “also now includes wading through hip-deep water on your way to work. And maybe filming it.” This purported civic responsibility to film subway floods signals a latent danger that the infrastructural critique offered by subway flood videos could become normalized, each video one more content contribution to communicative capitalism. Leyda and Negra’s warning for the spectacularization of extreme weather events thus proves equally valuable to these events’ transformation into everyday genres: hypermediation cannot “take up the slack” for the substantive public conversations or for the feeling of powerlessness that accompanies the realization that climate-induced catastrophes will be unavoidable in the future.

The framing potentials of these videos lie in their succinct link between extreme weather and infrastructural disrepair and in their bridging of subjective and omniscient perspectives to witness both these events in tandem. However, there is also a risk that their prevalence becomes something of a salve that helps deal with the normalization of increasingly more extreme weather and more infrastructural decay. Even more simply, we should be very wary that, as one Twitter user put it, “climate change will manifest as a series of disasters viewed through phones with footage that gets closer and closer to where you live until you’re the one filming it.”

Image Credits:

- MTA New York City Transit responds to a water main break at West 41st St. & 7th Av. Image by, Marc A. Hermann / MTA.

- TikTok video posted by user @gl00mie_ on September 1, 2021

- Screenshot of tweet by user @ryanryan_hi on September 1, 2021

- Screenshots of video posted by Twitter user @AlexEtling on September 1, 2021

Berlant, Lauren. (2011). Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press.

Bowker, Geoffrey. (1994). Science on the run: Information management and industrial geophysics at Schlumberger, 1920-1940. MIT Press.

Hetherington, Kregg. (2019). “Introduction: Keywords of the Anthropocene.” In Infrastructure, Environment, and Life in the Anthropocene, ed. K. Hetherington, 1-18. Duke University Press.

Larkin, Brian. (2013). “The politics and poetics of infrastructure.” Annual review of anthropology 42(1), 327-343.

Leyda, Julia, and Diane Negra. (2015). Extreme Weather and Global Media. Routledge.

Rust, Amy. (2016). “‘Going the Distance’: Steadicam’s Ecological Aesthetic.” In Sustainable Media: Critical Approaches to Media and Environment, eds. J. Walker and N. Starosielski, 146-160. Routledge.

Walker, Janet, and Nicole Starosielski. (2016). “Introduction: Sustainable Media.” In Sustainable Media: Critical Approaches to Media and Environment, eds. J. Walker and N. Starosielski, 1-21. Routledge.