K-pop Fandom is Fast Becoming an Empowering Space for LGBTQ+ Youth Around the World

Thomas Baudinette / Macquarie University

Blackpink, Ateez, Le Sserafim, Stray Kids, NewJeans.

This is a short list of K-pop groups who have recently headlined major Western music festivals such as Coachella and Lollapalooza, speaking to the growing impact of South Korea’s music industry on the global pop culture landscape. Driven by extraordinary vocals, powerful choreography, songs with relatable social messaging, and innovative styling that pushes the limits of contemporary fashion, it’s no surprise that K-pop has become a transnational phenomenon with immense popularity over the past few years.

Behind K-pop’s impressive ability to shape both global musical trends and the world of high fashion are its transnational fandom cultures. One need look no further than the fans of K-pop powerhouse BTS, who continue to dominate social media trends and participate in highly coordinated online activist projects despite the fact that the band is on hiatus as several members complete their mandatory military service in South Korea. Fandom for K-pop groups such as BTS has become especially influential over the last decade due to the strong sense of community afforded by joining these ‘digital tribes’ (see Chang & Park 2019) primarily active on social media services such as Twitter/X, Instagram, and TikTok.

As an academic fan or ‘acafan’ who has been participating in K-pop fandom for fifteen years and who has been investigating the transnational circulation of Korean media, my research has identified that K-pop fandom has become an empowering space for one marginalized group that has been largely neglected in the previous scholarship: LGBTQ+ youth. In this brief essay, I draw upon the findings of my Academy of Korean Studies-funded project ‘Exploring K-pop Fandom as a Space for LGBT Support in the Asia-Pacific During Pandemic Times’ (AKS-2022-R033) to demonstrate how K-pop provides LGBTQ+ youth with resources to combat hetero-patriarchal social structures and advocate for queer emancipation.

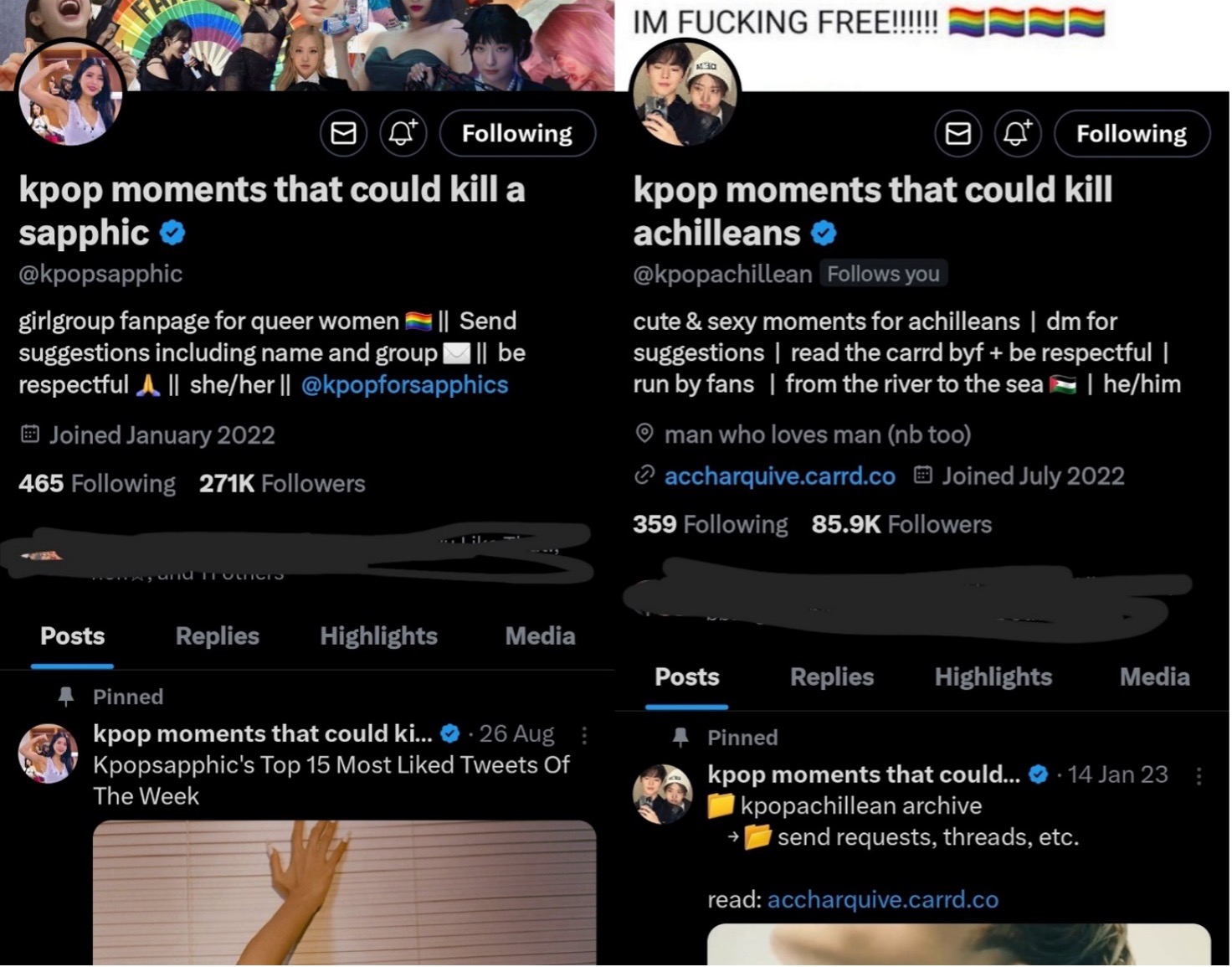

The popularity of K-pop among LGBTQ+ youth can be quickly established with a cursory survey of Twitter/X, where large fan clubs for queer men and women have emerged in recent years. Two prominent examples include ‘kpop moments that could kill a sapphic’ (@kpopsapphic) and ‘kpop moments that could kill achilleans’ (@kpopachillean), Twitter/X accounts dedicated to sharing pictures and videos of K-pop idols for LGBTQ+ audiences with 271,000 followers and 85,900 followers, respectively. According to the admins of @kpopachilleans, not only is the account dedicated to sharing ‘cute & sexy moments for achilleans’ – a term for men who love men popular among Gen-Z youth – the fan site also represents a space for marginalized LGBTQ+ fans to communicate with one another in an empowering environment.

It is common to witness viral posts on Twitter/X produced by LGBTQ+ fans which celebrate not only their attraction to K-pop idols (thus affirming these fans’ queer sexuality) but which also participate in playful fandom practices such as ‘shipping’ where fans re-imagine idols in same-sex romantic and sexual relationships. Drawing upon the fundamentally playful and transformative nature of fandom, fan clubs such as @kpopsapphics and @kpopachilleans not only serve to connect LGBTQ+ fans with communities grounded in shared queer experience, they also visibilize the presence of LGBTQ+ fans within a fandom culture that is often stereotyped as solely catering to heterosexual women.

My investigations with Kelsey E. Scholes of young LGBTQ+ fans in both Australia and the Philippines uncovered that many turned to social media services like Twitter/X precisely because of the care that other members of K-pop fandom took in ensuring that fan clubs on these online spaces were welcoming to sexual minorities (Baudinette & Scholes 2024). Just as LGBTQ+ youth flocked to fandom for Western TV shows such as Sherlock (2010-2017) or Supernatural (2005-2020) on social media sites such as Tumblr in the 2010s (see Cavalcante 2019), LGBTQ+ youth in the early 2020s look to K-pop fandom on Twitter/X as an always already safe space for those whose desires and identities are marginalized by mainstream society.

There was a broad belief among our LGBTQ+ fan interlocutors that K-pop fandom, whether it be online or in physical spaces such as fan events or at concerts, represented a space where they could not only express their queer desires for K-pop idols but also where they could learn about their queer sexuality through discussions with other LGBTQ+ fans (Baudinette & Scholes 2024). Through their fan discourses and their community building activities both online and offline, LGBTQ+ fans of K-pop therefore transform the genre into a ‘resource of hope’ that ‘reject[s] heteronormativity… [and] disrupt[s] the problematic everyday to produce futures which are both emancipatory and empowering’ for marginalized, queer communities (Baudinette 2022: 51).

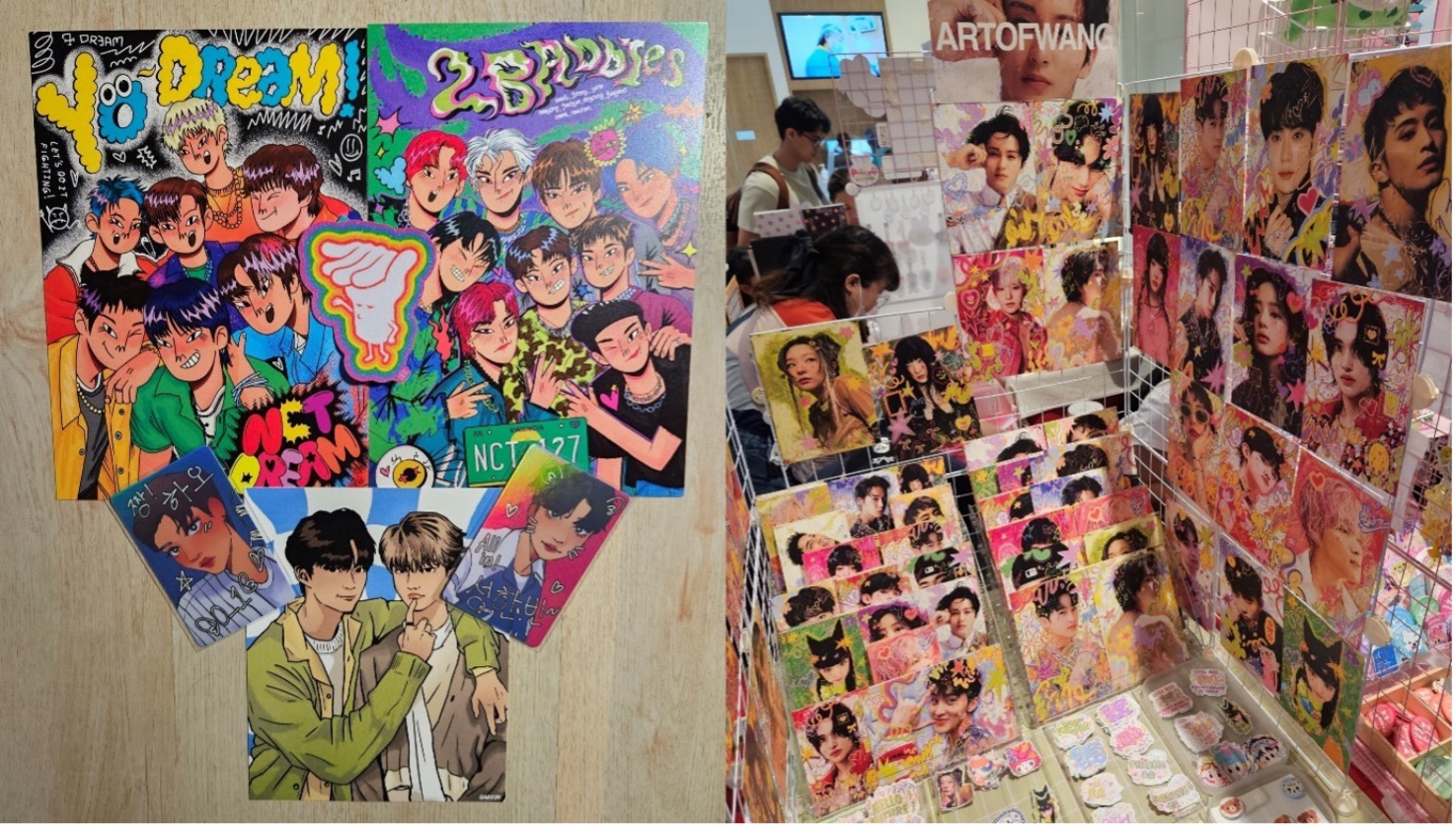

For fans located in societies which are especially homophobic such as the Philippines, where Catholic and other colonial value systems imported from the West have suppressed local queer knowledges, the importance of K-pop fandom in opening a space for LGBTQ+ youth to safely explore and express their queer desires cannot be over-stated. In fact, many fans of Korean media who I met at Komiket Pride, an art market for LGBTQ+ content creators that I attended during a research trip to Manila in June 2024, explained to me how transnational K-pop fandoms were producing solidarities among LGBTQ+ youth across Asia. In so doing, these youth transform K-pop fandom into a space replete with decolonial queer potential, providing LGBTQ+ fans with tools to reject the heteronormative ideologies introduced into the region by successive waves of colonization by Western imperial powers.

Finally, K-pop idols’ playful gendered performances are emerging as important sources of queer knowledge for fans who identify as non-binary, genderqueer, or trans (Baudinette & Scholes 2024). Considering the fact that K-pop has been celebrated for its normalization of androgynous styling and its performative challenge to stereotypical gender roles, it is unsurprising that many LGBTQ+ fans have turned to K-pop idols’ fashion as a resource to reject heteronormative gender ideologies.

Such sartorial challenges to the gender binary were on full display, for example, in a recent episode of K-pop group Stray Kids’ YouTube-based variety show One Kid’s Room where Korean-Australian member Felix spoke candidly about his desires to normalize unisex fashion, grow his hair long, and reject toxic masculinity. I learnt through my conversations with LGBTQ+ fans that mimicking the playfully androgynous gendered performances of idols like Felix helped many develop their own personal style in ways that pushed back against gender-restrictive sartorial norms (Baudinette & Scholes 2024). In fact, for fans who identified as trans that I have interviewed in Australia, support for gender-neutral fashion by beloved K-pop idols was drawn upon as a resource to affirm their own trans identity at a time of rising transphobia around the globe.

Overall, it is clear that K-pop fandom has evolved into an empowering resource for LGBTQ+ youth. But underneath this reparative narrative of LGBTQ+ empowerment lies a paradox. While LGBTQ+ fans look to Korean media as a ‘resource of hope,’ South Korea remains a nation that is hetero-patriarchal, misogynistic, homophobic, and transphobic. Future research will be needed to explore just why the queer emancipatory impacts of K-pop fandom among international fans such as those whose experiences I have recounted in this essay have yet to fully manifest within the society which gave birth to the genre.

Image Credits:

- Ateez Performs at Coachella 2024.

- K-pop fan clubs on Twitter/X catering to LGBTQ+ fans (author’s screen grabs).

- De-identified posts from Twitter/X shipping Sung Hanbin and Zhang Hao of ZEROBASEONE (author’s screen grabs).

- K-pop fan art produced by LGBTQ+ content creators in the Philippines (author’s photographs).

- Felix of Stray Kids appearing in One Kid’s Room (author’s screen grab).

Baudinette, T. (2022). BL as a ‘resource of hope’ among Chinese gay men in Japan. In J. Welker (ed.), Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia (pp. 42-55). University of Hawaii Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824892234-007.

Baudinette, T., & Scholes, K. E. (2024). K-pop Fandom’s affective role in shaping knowledge of gender and sexuality among LGBTQ+ fans in Australia and the Philippines. Sexualities, online first, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607241275855.

Cavalcante, A. (2019). Tumbling into queer utopias and vortexes: experiences of LGBTQ social media users on Tumblr. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(12): 1715–1735. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1511131.

Chang, W. J., & Park, S. E. (2019). The fandom of Hallyu, a tribe in the digital network era: The case of ARMY of BTS. Kritika Kultura, 32, 260-287. https://doi.org/10.13185/2986.