Stranded in Osaka: Storytelling through TikTok

Trevor Boffone / University of Houston

I was stranded in Osaka. I had taken a whirlwind ten-day tour of Japan with a group of high school students, parents, and fellow teachers (31 travelers in all). After seeing Mt. Fuji, riding the bullet train (Shinkansen), and eating the world’s best ramen, it was time to go home. We arrived at the airport to make the long journey home to Houston when we learned there was an issue. American Airlines did not finish the code share with Japan Airlines. We had no tickets to make the first leg of our journey from Osaka to Tokyo. As we frantically tried to work out a solution with airline employees at the Osaka airport and via phone to American Airlines, we missed our flight. American Airlines bumped us from the rest of our journey. Suddenly, I was stuck in Osaka with a group largely comprised of teenage high school students. After over 24 hours of begging American Airlines and our tour company, EF tours, to help us, we were finally offered what was presented as the only solution—we were forced to fly from Osaka to Bangkok to Munich to Charlotte to Houston. The total flight time was 42 hours and over 50 hours door to door. To put it simply, it was a shit show.

By the time we arrived in Houston five days later, we were met at the airport by the local news who had been following our journey for several days. But how did our bizarre story become a bona fide national news story? It was all possible because of one thing: TikTok.

What began as a travel nightmare soon turned into a deep-dive into TikTok storytelling. Indeed, TikTok is a powerful platform not just for mindless entertainment but for sharing stories in an episodic manner that leans into the app’s features, aesthetics, and cultures. Yet, I question: How did my Japan experience change the way I tell stories on TikTok, if at all?

As a prolific TikToker myself (@official_dr_boffone, 307k followers), I was already in the throes of documenting my trip to Japan. I had danced in front of Nijo Castle in Kyoto. I had tried Japanese snacks from 7/11. I had crossed Shibuya among throngs of people. But despite consistently creating social media videos since early 2019, I had never truly left my comfort zone: collaborating with my students on videos showcasing our classroom culture (primarily dancing, taste tests, and games). As I walked to a 7/11 in Osaka to grab breakfast, I debated how I might share my Japan travel experience with my audience and, perhaps, if I was lucky, folks beyond my following. Considering social media has long been a home for storytelling (Mueller & Rajaram, 2023), it only seemed natural to use TikTok to tell the story of 31 high schoolers, teachers, and parents stranded in Osaka, desperately trying to return home. I didn’t just tell my story; rather, I weaponized my sizeable platform to draw attention to our plight.

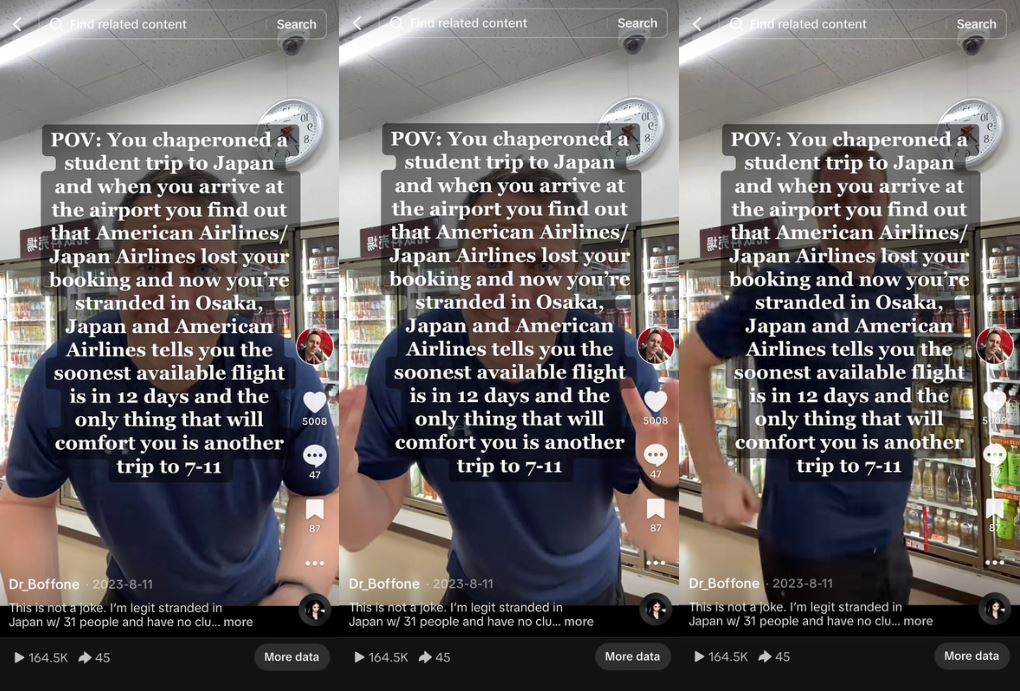

On August 11, 2023, I set up my camera on a shelf in a 7/11 in a quiet residential pocket of Osaka and begin dancing to a sped-up version of “Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You.” My face says it all—exhaustion, defeat, and a general “What the fuck am I supposed to do?” attitude. The video makes use of on-screen text, filling the screen and forcing the viewer to read, which ultimately lengthens the average watch time and, thus, improves the video’s algorithmic reach. The text tells the story:

“POV You chaperoned a student trip to Japan and when you arrive at the airport you find out that American Airlines/Japan Airlines lost your booking and now you’re stranded in Osaka, Japan and American Airlines tells you the soonest available flight is in 12 days and the only thing that will comfort you is another trip to 7-11”

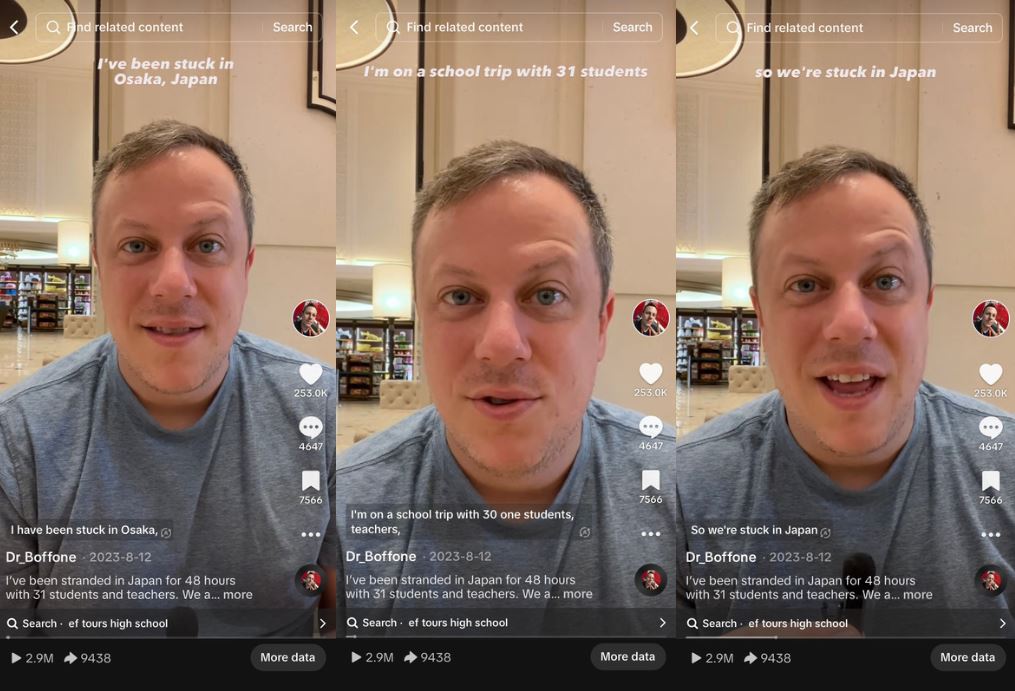

The video performed moderately well, attaining about 100,000 views within a day. Seeing the interest in our story, the next morning I posted a 2-minute-long video detailing the entire debacle. This video, “Stranded in Japan,” begins with a great hook: “I have been stuck in Osaka, Japan for two days. I’m on a school trip with 31 students…” I posted the video before boarding the flight to Bangkok. When I arrived in Thailand seven hours later, the video had over one million views on TikTok (not to mention hundreds of thousands of views on Instagram and Facebook). Our story had gone viral. In addition to thousands of comments, my DMs were soon filled with messages from airline employees desperate to help us, parents thanking me for posting updates about their children, and national US media outlets hoping to cover the journey, all examples that demonstrate how storytelling—when done well—can elicit audience affection (Triwidyati & Pangastuti, 2021).

The travelogue series continued with a montage of me gallivanting around the Bangkok airport, trying a pretzel in Munich (while looking especially busted), dancing in Charlotte with on-screen text explaining how the airline lost my luggage, and finally a video in which I speak directly to the camera responding to FAQs. These videos all performed well on TikTok, gaining over 100,000 views each (“Stranded in Japan” hit 2.9 million views).

TikTok is filled with gripping stories. In TikTok’s attention economy, creators need far more than a great story to attract and keep a viewer’s attention. Knowing this, I didn’t just present my story in a series of aesthetically repetitive videos. Of the six main videos, only two are direct address videos. The others all make use of tried-and-true TikTok storytelling devices that harmonize video, text, and audio (Vizcaíno-Verdú & Abidin, 2022). For instance, in several videos, I married a popular dance trend with onscreen text to tell a micro story. These videos perform well algorithmically because of not only the use of trending audio, but also on-screen text that tells an interesting story while something visually engaging happens behind it. Indeed, storytelling on TikTok is more than just speaking to the camera; rather, it includes a host of digital tools creators can use to enhance the story (Henneman, 2020). Moreover, trending audio trends for a reason. As viewers scroll TikTok, they inevitably grow accustomed to the sonic landscape of the platform. When they hear these songs and sound bites in subsequent videos, it creates a positive association with what they are hearing, which, I believe, encourages viewers to stay on a video for longer.

I am far from the first person to tell a serial story on TikTok. But what I learned was that stories on TikTok can live in different aesthetical playgrounds. The standard direct address videos remain crucial to TikTok storytelling, but, as I learned, by telling my story in an authentic way to my personality, my story was able to get viewers to stop scrolling and engage with my content. I was able to attract this attention precisely because I had spent over four years growing my audience and, along the way, teaching them about what they can expect from my platform. I didn’t change my content at all; I simply told my Japan travelogue within the parameters that I had already crafted on my TikTok account. My followers, just like any other spectators on TikTok—or any other social media platform for that matter—want to be entertained. That is at the heart of what makes TikTok click. Viewers want to watch interesting stories told in an engaging way. This looks different for every creator, but, for me, this looks like me dancing in a 7/11.

My story began with being stranded in Osaka. But my story ended with me and my students featured across the US media (I was even invited on The Drew Barrymore Show, an invitation I declined due to the WGA strike). TikTok gave me agency and self-determination to tell my story (Boffone, 2022). My experience encouraged me to expand the ways that I tell stories on TikTok. It taught me how to be more effective by using rhetorical devices already in my arsenal. It empowered me to just post the f*cking video, to just tell my story.

Note

I would like to thank Cristina Herrera and Danielle Rosvally for their feedback on earlier drafts of this essay.

Image Credits:- Author, fellow travelers, and the local news crew at Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston on August 14, 2023. Photo courtesy of the Author.

- Screenshots of Author’s TikTok video (August 11, 2023).

- Screenshots of Author’s TikTok Video (August 12, 2023).

Boffone, Trevor (2022). “TikTok is Theatre, Theatre is TikTok.” Theatre History Studies vol. 41, pp. 41-48. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/ths.2022.0028

Hennemen, Todd (2020). “Beyond Lip-Synching: Experimenting with TikTok Storytelling.” Teaching Journalism & Mass Communication vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1-14.

Mueller, Marie Elisabeth, and Devadas Rajaram (2023). Social Media Storytelling (Routledge). Available at: https://www.routledge.com/Social-Media-Storytelling/Mueller-Rajaram/p/book/9781032229256

Triwidyati, Endang, and Ria Lestari Pangastuti (2021). “Storytelling through the TikTok Application Affects Followers’ Behaviour Changes.” JAGADITHA: Jurnal Ekonomi & Bisnis vol. 8, no. 2. Available at: https://doi.org/10.22225/jj.8.2.2021.127-135

Vizcaíno-Verdú, Arantxa, and Crystal Abidin (2022). “Music Challenge Memes on TikTok: Understanding In-Group Storytelling Videos.” International Journal of Communications vol. 16, pp. 883–908. Available at: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/18141/3680