Air and the Managerial Sports Film

Branden Buehler / Seton Hall University

Although most movie audiences likely associate sports films with images of last-second touchdowns and slow-motion alley-oops, in recent years, a wave of sports films has moved the genre’s drama away from the playing surface and instead shifted it toward the conference room and the corner office. In these managerial sports films – movies like Draft Day (2014), Million Dollar Arm (2014), and Moneyball (2011) – the heroes are executives rather than athletes and tense athletic action is frequently deemphasized in favor of spectacularized phone calls and office meetings. As I argue in my book Front Office Fantasies: The Rise of Managerial Sports Media, this wave of administrative film narratives is of a piece with a broader turn within sports media toward management, with an increasingly wide range of sports media texts hyperfocused on the bureaucratic maneuvers of sports executives.

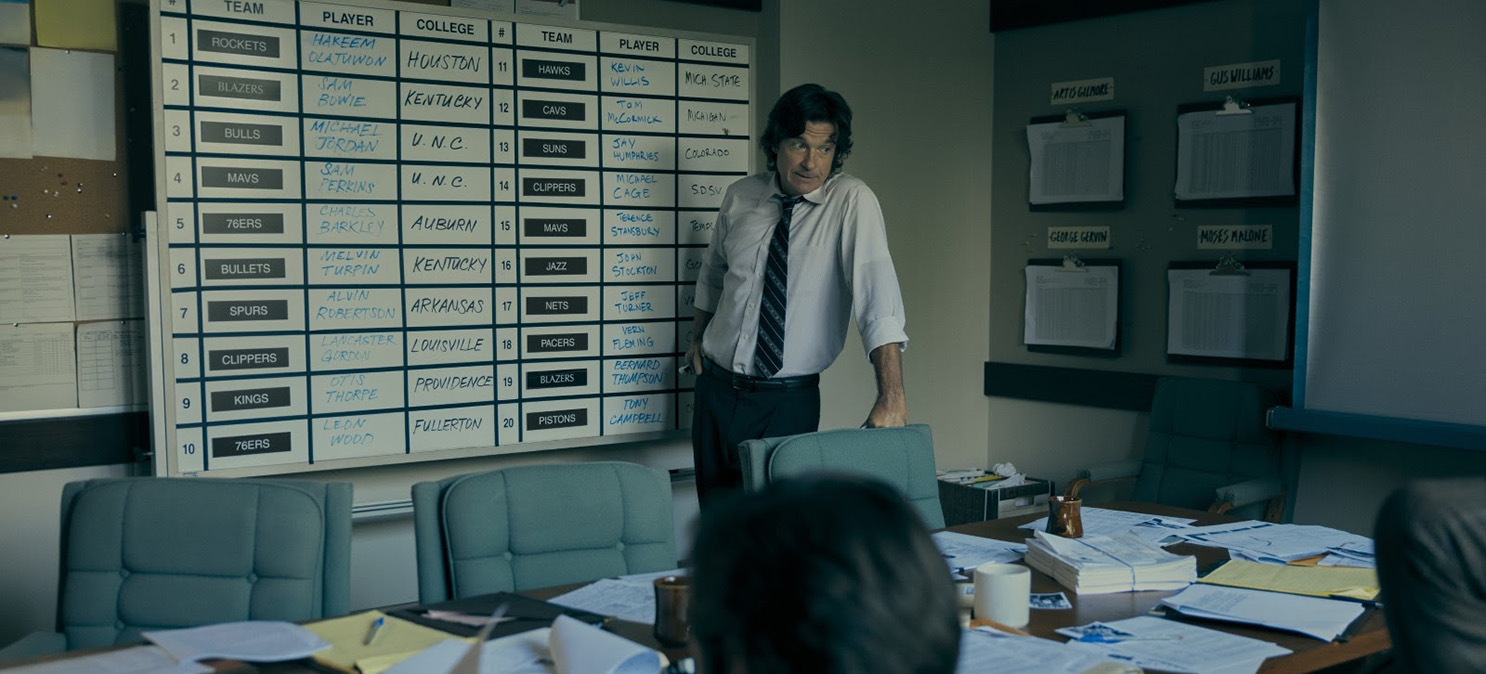

The 2023 film Air might be understood as the latest iteration of the managerial sports film subgenre. In the film, a group of Nike executives – Sonny Vaccaro (Matt Damon), Howard White (Chris Tucker), Rob Strasser (Jason Bateman), Phil Knight (Ben Affleck), and Peter Moore (Matthew Maher) – work to convince budding basketball superstar Michael Jordan to sign an endorsement deal with the company. In centering a group of executives, Air, much like other managerial sports films, approaches sport through the perspective of white-collar administrators, with sport thus figured largely as a site of bureaucratic heroism and in which many of the most consequential activities occur under fluorescent office lights. Lest it be said, though, that managerial sports films completely depart from the templates of the traditional sports film, several key staples of the genre generally remain within these bureaucratic tales. In the vein of the traditional sports film, for instance, Air joins these other administrative films in positioning itself as an underdog story, in this case by framing Nike as a “scrappy” upstart fighting against the entrenched basketball powers Adidas and Converse. Indeed, making this comparison to the familiar sports narrative explicit, one of the film’s protagonists draws parallels between Nike and Rocky Balboa.

If there is one general constant in the managerial sports film subgenre, it is the valorization of the manager acting on behalf of capital.[1] In Draft Day, for instance, the administrator protagonist – Kevin Costner playing a fictional Cleveland Browns general manager – is glorified for keeping disaffected players and staff in line, while in Moneyball, the executive lead – Brad Pitt playing Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane – is heroized for efficiently limiting payroll expenses. One of the most interesting aspects of Air, then, is how it potentially represents a twist on the subgenre by undercutting some of its familiar managerialist dynamics. Ostensibly, the second half of the film is about the power of athletic labor to resist capitalist exploitation – the apparent intention, it would seem, for the film to be a symbolically resonant first project for Affleck and Damon’s private equity-backed production company Artists Equity, which has touted greater profit participation for film “creators and crew.” One of the film’s closing centerpieces, for example, is a lengthy negotiation between Vaccaro and Michael Jordan’s mother, Deloris (Viola Davis), in which she pushes for her son’s endorsement deal to break industry norms by including a percentage of product sales in addition to a standard endorsement fee. In this back-and-forth exchange, Vaccaro insists that a revenue-sharing deal would be unimaginable. “People who work for a living, they don’t let us own anything,” he proclaims. “We take the best we can get.” Jordan, though, does not accept this appeal to the “unfair” status quo. “You eat, we eat,” she tells Vaccaro. “He deserves a piece.” In the end, the Jordans get their percentage deal and, according to the film’s epilogue, change the world of sport forever. “The precedent set by the deal,” on-screen text reads over an image of Deloris, “resulted in billions more dollars going to athletes and their families.” The epilogue also implicitly links the deal to college athletes’ fight to be compensated for their name, image, and likeness rights.

While these sorts of moments speak to a relatively unusual questioning of athletic exploitation within the managerial sports film, it is nonetheless a struggle to view Air as particularly progressive in its treatment of labor. While, for instance, the film valorizes Deloris Jordan’s unwavering commitment to the value of her son’s labor, her conversation with Vaccaro hardly represents a call for deep systemic change or collective action. That is to say, while Jordan might insist that her son “deserves a piece” of the fruits of his labor, she also seems to suggest it is largely just prodigious individuals like her son (or Affleck and Damon?) who can operate outside the exploitative capitalist status quo. “Every once in a while,” she tells Vaccaro, “someone comes along that’s so extraordinary that it forces those reluctant to part with some of [their] wealth to do so – not out of charity, but out of greed, because they are so very special.” This exchange, then, does not speak to a radical reimagining of the “unfair” system but rather to a minor tweaking of that system to benefit exceptional individuals.

It is worth highlighting, too, the uneven treatment of Michael Jordan in the film – a treatment that often serves, ironically, to dehumanize the very same individual who is narratively positioned as being at risk of capitalist exploitation. Throughout the film, Jordan is only glimpsed either in archival game footage or from the back of his head – Affleck, who also directed the film, commenting that Jordan is such a familiar figure that it would be distracting to “concretize” him. Moreover, Jordan’s voice is only momentarily heard in the film. Jordan, then, exists primarily to be spoken for by others. Frequently, the Nike executives discuss Jordan with a reverence typically reserved for holy subjects. Vaccaro, for instance, repeatedly emphasizes Jordan’s “greatness” and, in a pitch meeting, argues that “the rest of us just want to touch that greatness.” In fact, he tells Jordan at that same meeting, “Everyone at this table will be forgotten as soon as our time here is up – except for you. You’re going to be remembered forever because some things are eternal.” However, for all that reverence, Jordan – when the film approaches him more as a person than as a mystique – is also spoken of as a somewhat imprudent young man whose best interests are perhaps better left to others, including not just his mother and agent but also the underdog visionaries at Nike. Throughout the film, for instance, it is a running joke that, amid the momentous struggle for his endorsement, Jordan himself is just looking for a red Mercedes, with the epilogue noting that after signing with Nike, “Michael got his car.”

Air’s labor politics, including the distant, occasionally condescending treatment of Jordan, come into better focus when the movie is considered alongside other managerial sports films. In heroizing sports administrators serving the interests of capital, managerial sports films have repeatedly treated athletes more as commodities than as individuals. Draft Day’s executive protagonist, for example, proudly advertises his unfettered ability to cast off a disgruntled quarterback if he so chooses, telling the player, “If I trade you, I trade you; if I don’t, I don’t … don’t bother me with your shit.” In Moneyball, meanwhile, athletes become faceless, interchangeable assets to be bandied about in trade negotiations with other executives. Notably, too, these sorts of power dynamics are racialized and gendered within managerial sports films, as – fitting with the broader genre’s long-held interest in remasculinizing straight white men – these sorts of scenes repeatedly suggest it is white men in administrative roles who are the true center of sport.[2]

In gesturing away from collective action and offering a flattened depiction of the athlete superficially at its narrative core, Air might be best understood as ultimately reinforcing the subgenre’s typical managerialist dynamics rather than subverting them. That Air, for all its attempts to speak to athlete empowerment, would fall back into the subgenre’s typical trappings is hardly surprising, however. This is, after all, a film about using Jordan to sell sneakers. With that in mind, when Vaccaro emphatically pitches a new Nike sneaker around the idea that Jordan “doesn’t wear the shoe; he is the shoe,” it would be prudent to take this line at face value. As Aaron Dial argues, “Michael Jordan isn’t the film’s subject, but its object.” The view of athletes within Air, as it so often is throughout the managerial sports film subgenre, is that they are best regarded as assets.

Image Credits: References:

- The one notable exception to this tendency is the subversive High Flying Bird (2019), which consistently suggests much of the sporting apparatus is parasitic. [↩]

- In the case of Air, it is perhaps telling that in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Affleck revealed that the only Nike executive in the film who is not white, Howard White, was not originally in the script and was only added to the film after conversations with Jordan. [↩]