Over*Flow: “It’s Not Steroids, It’s Testosterone!”: Deconstructing Gender and Sex in Bros (2022)

Lauren Herold / Kenyon College and Nicole Erin Morse / Florida Atlantic University

In recent years, a coordinated national legislative assault on transgender rights has shaped culture war political debates across the country. As queer scholars of queer media, we have experienced this backlash from our respective homes in Florida and Ohio, where our conservative legislatures are busy proposing one anti-trans bill after another. Under the guise of “protecting the children” and preserving “traditional family values,” right-wing politicians have proposed bills to outlaw medical care for trans people, ban drag performances, and bar trans people from participation in public life. These politicians claim that trans people are unnatural and assert that sex is a binary, biological, natural, and immutable fact defined at birth. Gender identity, they say, is just made up, and they’ve been busy removing “gender” from non-discrimination policies and curtailing the academic freedom of gender studies programs in colleges and universities.

At this moment, somewhat to our surprise, we found ourselves turning to an unexpected source for insight: Billy Eichner’s 2022 semi-satirical gay rom-com Bros. Hitting theaters amid this right-wing backlash against LGBTQ people, Bros appeared to some critics to be a failure of representational politics. On the surface, the film reproduces a normative standard of white cis gay masculinity, epitomized by Aaron (Luke Macfarlane), the muscular love-interest in the film. Starring two cis white gay male actors playing cis white gay men, Bros relegates its lesbians, bisexuals, trans people, and people of color to small supporting roles rife with stereotypes. It seemed out of touch with the historical moment despite its own commitment to satirizing tokenism and to creating an inclusive working environment.

To Eichner’s well-publicized chagrin, Bros was also a failure at the box office. On Twitter, Eichner claimed that “straight people, especially in certain parts of the country, just didn’t show up for Bros.” Meanwhile, LGBTQ viewers expressed frustration with Eichner’s sense of entitlement to their time and attention. (Film critics at Variety rightly nuanced Eichner’s claims, arguing that a host of other issues were likely to blame for its lackluster box office performance.) In a time like this, did any audience – LGBTQ or not – really need a story about the romantic travails of upwardly mobile cis gay white men?

Reading against the grain, however, we discovered that the film’s comedic sequences skewering aspects of white gay life in the Northeastern United States inadvertently deconstruct the naturalness of cis gay masculinity. Almost as if they’re responding to anti-trans arguments from the right, several scenes in Bros show how gender (presentation and identity) and sex (physicality and hormones) aren’t natural, original, or simply “given.” In these scenes, Bros makes the same radical critique as Judith Butler’s queer theoretical text Gender Trouble: that both gender and sex can be constructed, modified, and changed.[1]

These scenes draw on tropes and themes from trans representation in order to examine cis gay masculinity. During a romantic getaway, Eichner’s character Bobby accidentally walks in on Aaron self-administering testosterone. In response to Bobby’s startled reaction, Aaron quickly clarifies, “it’s not steroids, it’s testosterone!” Steroids, it seems, imply cheating and inauthenticity, while testosterone, by contrast, is a medically authorized form of body modification. When Bobby wonders about the safety of taking testosterone, Aaron adds, “Half the guys I know do this stuff.” Bobby quips, eliding the distinction between testosterone and steroids, “Yeah, but half the guys you know are roided-out morons,” to which Aaron responds, “Yeah, well, that doesn’t seem to bother you when you’re obsessing over my body.”

This scene establishes one of the film’s key conflicts: while Bobby rails against his exclusion from gay ideals of gay masculinity, he simultaneously desires men who embody those ideals. Through this scene, Bros reveals that idealized gay masculinity is constructed rather than natural. Like many transmasculine people who take testosterone to masculinize their bodies, Aaron takes T to achieve a more muscular body type. This scene reverses the trope of the “reveal” in trans media,[2] showing that cis people use hormone replacement therapy as well. In its frank discussion of steroid use amongst gay men, Bros points to how their bodies are often constructed via what Paul Preciado would call “pharmacopornographic” regimes, in which all our bodies can be made and re-made (and regulated) by pharmaceutical drugs including hormonal birth control, HRT, and SSRIs.[3]

After breaking up with Aaron, Bobby takes steroids himself in an attempt to achieve the masculine ideal. In a scene played for laughs, we watch Bobby visit a gym, where he locks eyes with another gym goer, a muscular Black man in a backwards baseball cap. In slow motion, Bobby stands up from his exercise machine, flips his own cap backwards, and approaches the man with: “Hey bro.” In the scene, he speaks in a lower register and introduces himself as “Rob.” We cut to the two men in bed: clearly, it seems, Bobby’s attempt at seducing this man with his new bro masculinity has worked. But during post-coital conversation, Bobby uses his normal voice, shocking and confusing the other man, who tells Bobby to leave. On the way out of the apartment, Bobby notices a Barbra Streisand poster by the door: “This is actually kind of like Yentl, if you think about it!” Bobby says, before the other man replies, “Dude, get the fuck out!”

This scene is another example of Bobby comically navigating the body hierarchies and norms of gay sexual culture. In Bros, masculinity is a (racialized) construct that one can try on, perform, play with, manipulate, and discard. When Bobby forgets to maintain the performance and is “found out,” it is another example of the trope of the reveal. The reference to Yentl, a film often read as a transmasculine story, heightens this parallel. As Miriam Abelson writes, norms and expressions of masculinity shift over time and space and are shaped by race, class, geography, and sexuality.[4] Indeed, it does not seem like a coincidence that Bobby’s only sexual encounter with a person of color occurs while he is trying on hypermasculinity, as Black men have historically been represented as hypermasculine in American popular culture. Through comedy, Bros examines what Dwight McBride calls “the gay marketplace of desire,” a term which describes the centrality of whiteness in gay sexual cultures and which leads to the fetishization and dehumanization of Black gay men.[5]

Moreover, in deconstructing the idea that masculinity is unified and natural, Bros provides material that can challenge misogynistic dismissals of femininity. As trans feminist writer Julia Serano has argued, masculinity is considered “natural” and “sincere” while femininity is often seen as inherently “artificial” and inferior.[6] Bros explores how femininity is socially and sexually devalued in gay male sexual culture, yet it simultaneously reverses this dynamic: masculinity is the artificial gender performance and Bobby’s somewhat more femme gender presentation is the “natural” grounds on which his bro masculinity must be built.

As Bobby shapeshifts his way through the gay marketplace of desire, we watch him come to terms with his own embodiment. Through these scenes, Bros explores how cis people construct their gendered and sexed selves, revealing that there may be more in common between trans and cis people than we might assume. As scholars like Finn Enke[7] and Kadji Amin[8] have recently discussed, terms like “cis” and “nonbinary” are not necessarily stable personal identities, but are taxonomic categories that reproduce binary ways of thinking about gender. While these terms are useful politically, they naturalize binary categories like cis/trans and binary/nonbinary. In Bros, comedy collapses these distinctions, suggesting the differences between trans and cis might not be as clear cut as we tend to think.

As we search for tools to combat right-wing transphobia, we can find inspiration in such close readings of “bad objects” like Bros in LGBTQ and feminist film.[9] It is perhaps not surprising that the ambiguous ending of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (2023), in which the eponymous doll decides to become a woman, inspired resistant readings of the film from a number of viewers on Twitter who suggested that the ending evokes narratives of trans femininity and interrogates the meaning and definition of womanhood itself.

In her visionary piece, “The Transfeminist Manifesto,” Emi Koyama writes, “Transfeminism believes that we construct our own gender identities based on what feels genuine, comfortable, and sincere to us as we live and relate to others given social and cultural constraint. This holds true for those whose gender identity is in congruence with their birth sex, as well as for trans people.”[10] A transfeminist reading of Bros allows us to see how the cis gay men on screen construct and reconstruct their self-expressions of masculinity. In a cultural moment in which anti-trans activists spectacularize transfemininity, delegitimize transmasculinity, and seek to deny the reality of gender while re-entrenching the bioessentialism of sex, the film’s focus on the ways we all construct gender can help shift the terms of the debate.

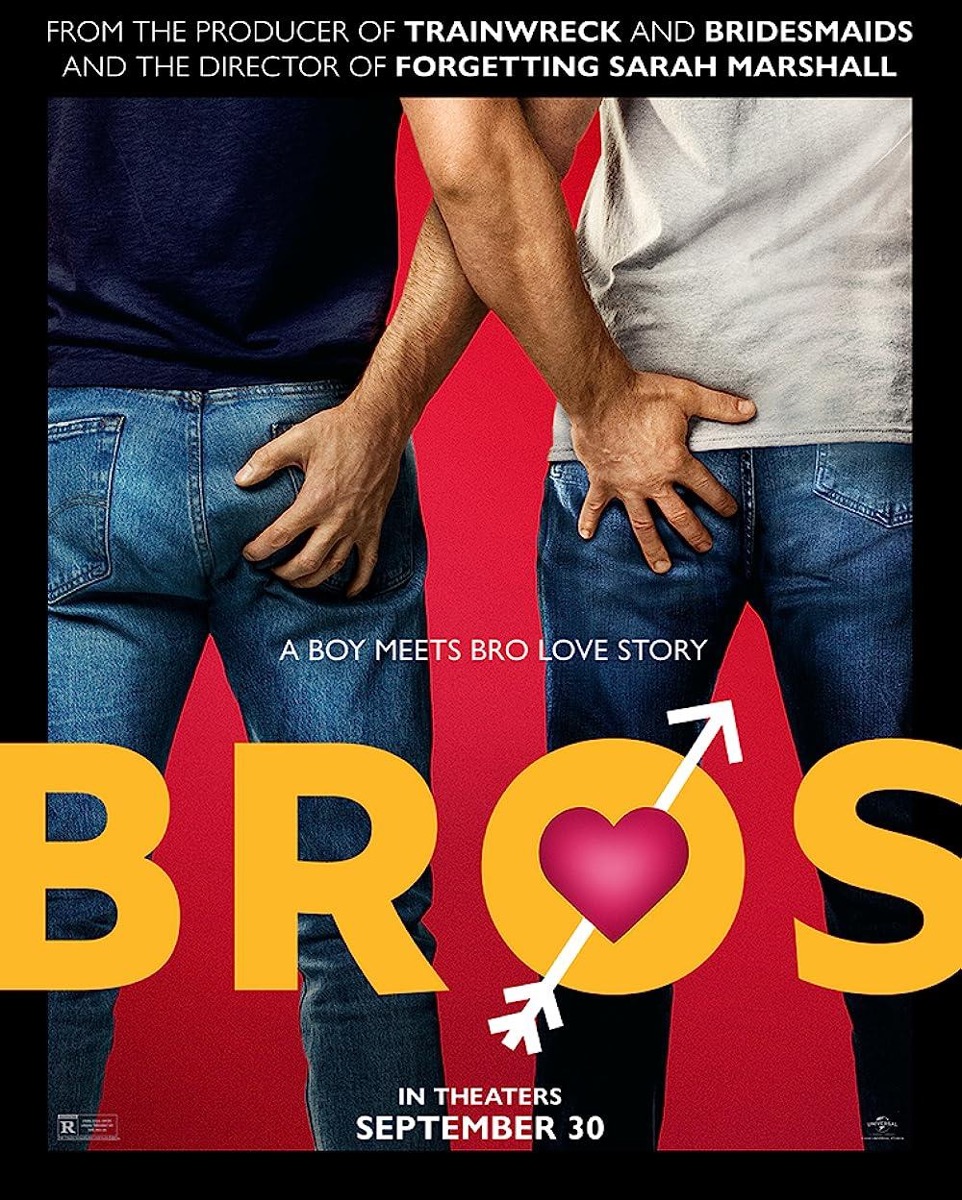

Image Credits:

- The promotional poster for Bros (2022), via IMDB.

- In Bros, Aaron (Luke Macfarlane) embodies the constructed ideal of white gay masculinity, via IMDB.

- At the gym, Bobby flips his cap backwards to appear more normatively masculine, via Universal Pictures’ YouTube (authors’ screengrab).

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Routledge, 1990). [↩]

- Danielle M. Seid, “Reveal,” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 1, no. 1–2 (May 1, 2014): 176–77, https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2399947. [↩]

- Paul Preciado, Testo Junkie (The Feminist Press, 2013), https://www.feministpress.org/books-n-z/testo-junkie. [↩]

- Miriam Abelson, Men in Place: Trans Masculinity, Race, and Sexuality in America (Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2019), https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/men-in-place. [↩]

- Dwight A. McBride, Why I Hate Abercrombie & Fitch: Essays on Race and Sexuality (New York: New York University, 2005). [↩]

- Julia Serano, Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity (Seal Press, 2007), https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/julia-serano/whipping-girl/9781580056229/?lens=seal-press. [↩]

- Finn Enke, “The Education of Little Cis: Cisgender and the Discipline of Opposing Bodies,” in Transfeminist Perspectives: In and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies (Temple University Press, 2012), 60–77. [↩]

- Kadji Amin, “We Are All Nonbinary,” Representations 158, no. 1 (May 1, 2022): 106–19, https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2022.158.11.106. [↩]

- Cáel Keegan, “In Praise of the Bad Transgender Object: Rocky Horror,” Flow 26, no. 3 (November 28, 2019), https://www.flowjournal.org/2019/11/in-praise-of-the-bad/. [↩]

- Emi Koyama, “The Transfeminist Manifesto,” in Feminist Theory Reader, ed. Carole McCann, Seung-kyung Kim, and Emek Ergun, 5th ed. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2020), 83–90, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003001201-12. [↩]