Disrupting Screenplay Format’s Attachment to White Space

Jess King / DePaul University

I’ve written elsewhere about how screenplay structure whitens, straightens, and otherwise infuses normative violence into screen stories through a false distinction between character and characterization, an over-reliance on conflict as narrative engine, and the ideological attachments of three-act structure (King 2022). What I haven’t discussed at length, however, is how screenplay format curtails possibilities for cultural specificity and “organic representation” (Christian and White 2020) through an attachment to “white space.”

As a narrative form and industrial blueprint for production, screenwriting favors efficiency through precise rules about margins, spacing, and font. For instance, Courier 12 is the standard screenplay font because, as a fixed-pitch font, the width of each letter takes up the same space on the page whether it’s a slender ‘i’ or a rotund ‘o.’ Uniformity of width allows for one page of text to translate roughly into one minute of film, making budgeting and scheduling easier for producers. Additionally, formatting is tied to practices of narrative economy that favor concision, eliminating narrative excess as a cost-saving measure.

Minimalist imperatives are often communicated in relation to how much “white space” one encounters on the page. Amateur writers who compose lengthy action blocks are admonished and told that “[s]easoned writers ensure that their pages contain abundant white space” because “[w]hite space allows script pages to breathe” (Riley 2009: 18). Contemporary screenplay wisdom promotes action paragraphs limited to three or four lines to support the “one page, one minute” rule. We’re warned that professional script readers encountering a page crammed full of black print become overwhelmed because the “[l]ack of this essential white space takes a strong psychological toll on the reader” (Riley 2009: 18). Thus, ideal action blocks require sparse prose for maximum impact. While such constraints can produce artful prose, the imperative for brevity via “white space” for the sake of “breathing space” leads me to questions about what kinds of characters can populate such spaces, or, put another way, whose ability to breathe is prioritized and who is policing this imperative?

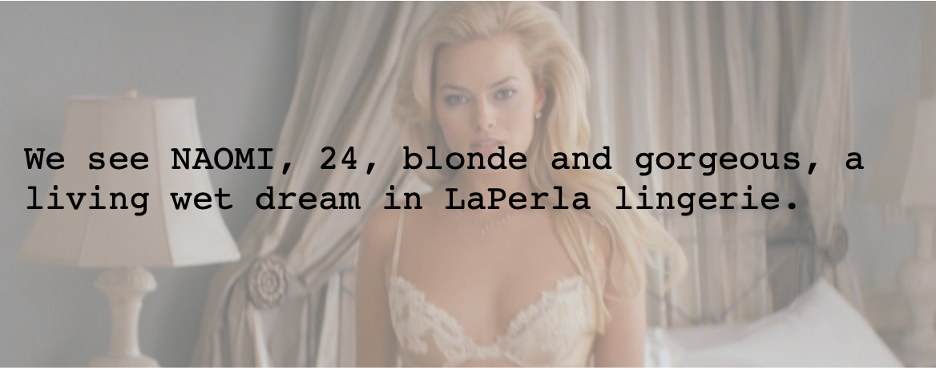

When white space is prized, there’s a pressure to adhere to a screenplay shorthand that favors universalist character design while treating characterization—things like race, gender, ability, etc.—like window dressing. We see snappy character descriptions including only name, age, level of attractiveness, and perhaps a fun quirk. In the Wolf of Wall Street (2013), for instance, the main character, played by Leonardo Di Caprio, is introduced as “JORDAN BELFORT, handsome, 30” (Winter: 1). We know this guy: he’s the (anti-)hero of every film; no need to say more. Later, his love interest, played by Margot Robbie, is introduced with only slight embellishment: “We see Naomi, 24, blonde and gorgeous, a living wet dream in La Perla lingerie” (Winter: 3). Again, the presumption is that we don’t need to know anything else about her, not her background, not her point of view. Her identity as a white, straight woman (objectified by the male gaze) is universally and instantly recognizable.

Such shorthand relies on a mythical norm, defined by Audre Lorde as as “white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, and financial secure” (Lorde 2007: 116). Those norms are never named or written, except for occasionally, such as when blondness underscores whiteness or expensive lingerie confers wealth. We begin to see how preserving “white space” is preserving the dailiness and transcendent universality of whiteness (Shome 1996).

When the assumption of whiteness (and other majoritarian affinities) is associated with efficiency, to be something else means taking up too much space. So what happens when screenwriters want to center stories on characters outside of the mythical norm? Because Black and Indigenous and trans and female and disabled people move and think and act differently in the world, naming and describing the nuances of those lives requires space to describe context, history, identity, and point of view. Words start piling up, because there is no universal, no shorthand. Thus, contextualizing characters with intersectional identities encroaches on white space.

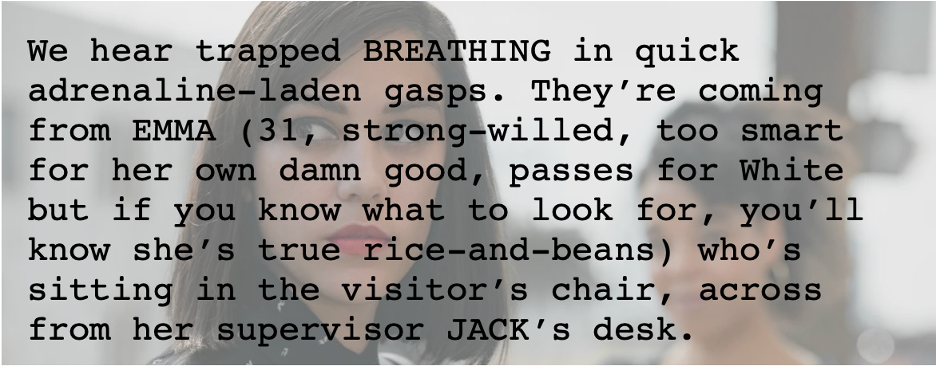

The pilot script for Tanya Saracho’s Vida is one that eschews dictates around white space to honor and develop a uniquely Latine world. Set in Los Angeles’ gentrifying Boyle Heights neighborhood, Vida (Starz, 2018-2020) follows sisters Lyn and Emma Hernandez as they cope with the death of their mother and come to terms with their complicated and evolving family history. Consistent with lengthy descriptions throughout the script, Saracho’s introductions to her primarily Latina (and queer) characters indulge in the intricacies of identity. In particular, the parentheticals for the characters distill essential characteristics that for “white space” stumpers might seem unnecessary embellishments of characterization. In taking the space to describe Emma as “31, strong-willed, too smart for her own damn good, passes for White but if you know what to look for, you’ll know she’s true rice-and-beans,” (3) Saracho hints at Emma’s borderland consciousness (Anzaldúa 2012: 100) as a Latina in a white world, not a superficial descriptor, but rather deeply wedded to the themes and struggles that persist throughout the series as a whole.

The way Saracho holds space to describe the intricacies of the Latine world of Vida is so striking that upon reading the pilot for the first time, a former student responded that as a Latine person he felt seen and empowered by Saracho’s fearlessness in claiming space to flesh out dimensional queer and Latine characters, something which he’d been discouraged from in film school.[1] In essence, Saracho allows herself, her characters, and the Latine audience she honors to breathe and, in doing so, seizes space usually relegated to the white void.

What is one to do with this knowledge? There’s a tendency to accept technological processes or rules as fact or ‘just the way it has to be,’ and this occurs with our filmmaking and screenwriting norms. We know that we are in an age of purposeful cinematic disruption focused on acknowledging and fixing past practices that barred equity onscreen. For example, in order to counteract the unspoken and ‘traditional’ techno-racist film stocks and lighting practices that have white-washed and invisiblized Black people on screens for a century, cinematographers like Rachel Morrison (Fruitvale Station), James Laxton (Moonlight), and Bradford Young (Pariah) have worked to reorient how Black actors are lit to highlight Black dimensionality. In a similar vein, in order to counteract the ways that the male gaze objectifies women and codifies agency for men, Joey Soloway has worked with cinematographers to shift towards a sensing/feeling camera that feels with the subject (regardless of gender) for what one might call a more empathic gaze.

Just as critiques of the white, male gaze have resulted in cinematographic innovation, there is room to challenge screenplay form. Writers like Saracho create space for their characters to be named and described, to exist and to breathe. The nuances of intersectional lives deserve space on the page. Occupy that space and see what happens.

Image Credits:

- Emma & Lynn in Vida, Starz (2018-2020).

- Wolf of Wall Street (2013) with screenplay text superimposed (author’s screen grab).

- Vida (Starz) with screenplay text superimposed (author’s screen grab).

Anzaldúa, G. (2012), Borderlands: La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 4th ed, San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Christian, A. J. and K. C. White (2020), ‘Organic Representation as Cultural Reparation’, JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, 60 (1): 143–47.

King, J. (2022), Inclusive Screenwriting for Film and Television, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

Lorde, A. (2007), Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Berkeley, Calif: Crossing Press.

Riley, C. (2009), The Hollywood Standard: The Complete and Authoritative Guide to Script Format and Style, 2nd ed, Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Saracho, T. (2016), ‘Pour Vida’, Unpublished Screenplay Manuscript.

Shome, R. (1996), ‘Race and Popular Cinema: The Rhetorical Strategies of Whiteness in City of Joy’, Communication Quarterly, 44 (4): 502–18.

Winter, T. (n.d.), ‘Wolf of Wall Street’, Unpublished Screenplay Manuscript.

- Thank you to Elías Ureña for sharing insightful commentary about his film school experience along with his enthusiasm for Vida and the ways Saracho breaks with tradition in refreshing ways. [↩]