Workers of the World BeReal!: BeReal and The Performance of Labor

Emily Lynell Edwards / St. Francis College

On BeReal the mundane reigns supreme (Herrman 2022). Unlike other image-centric social media apps such as Instagram or even Snapchat, BeReal is centered and designed around forcing users into a mien of banality through its structured design of snapping a random, timed image once a day. While there’s a devoted following for accounts like @bestbereals on platforms such as Twitter which curate a feed of the most zany BeReals, like users getting married (guilty as charged), crashing their cars, or my personal favorite, having an IUD inserted (Guinness 2022), these are exceptions to the rule.

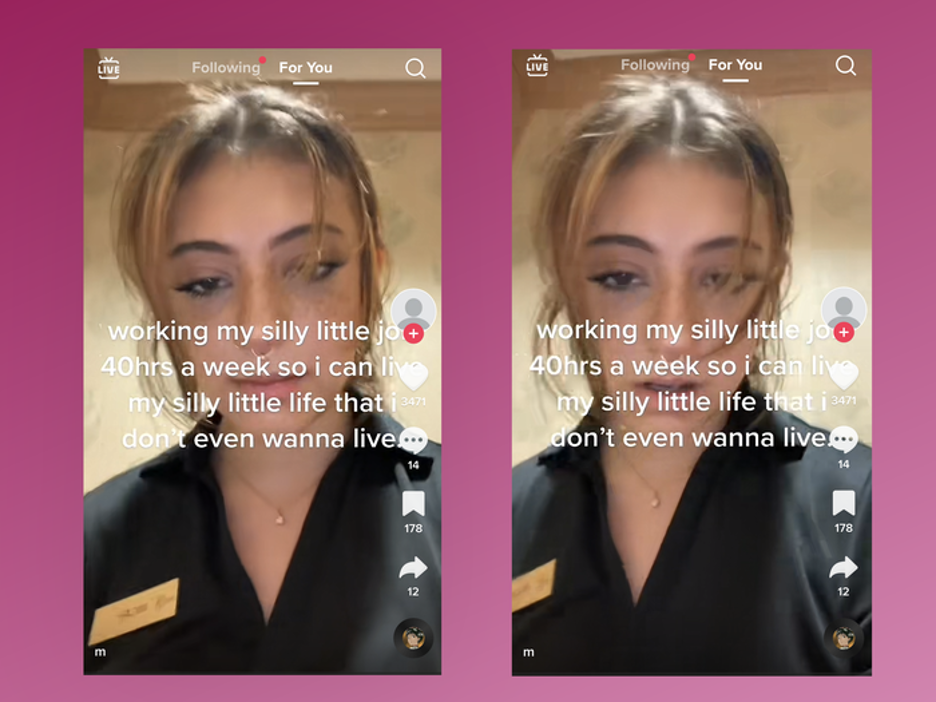

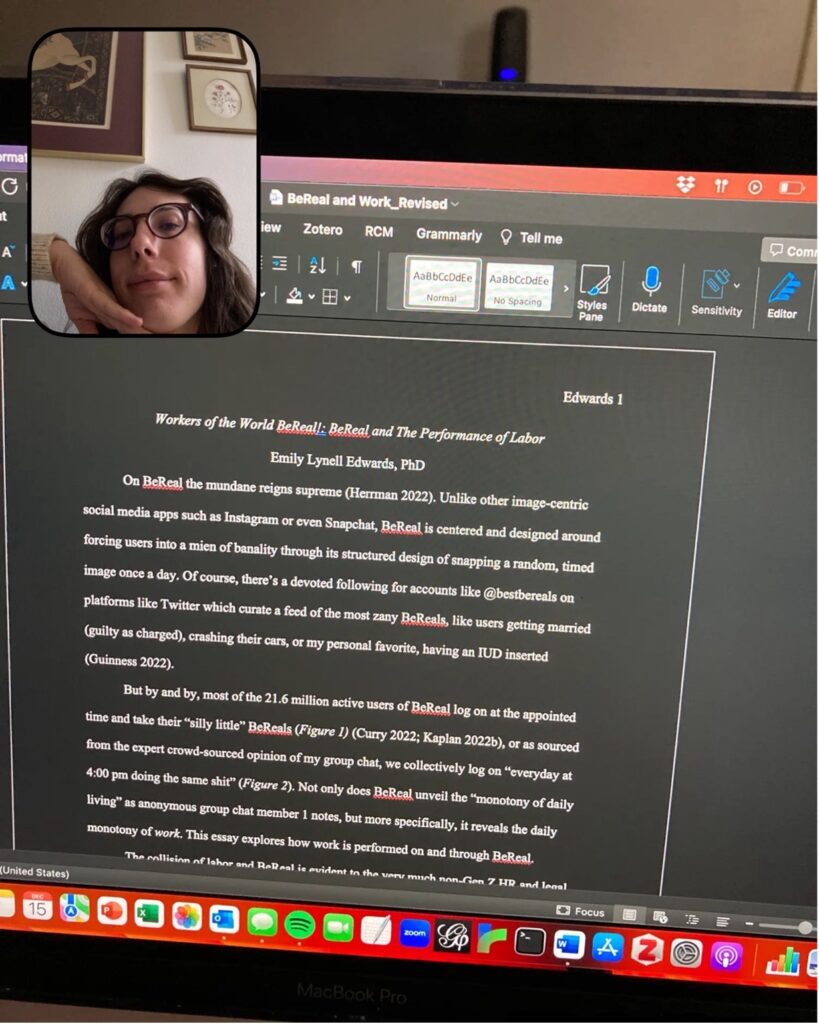

But by and by, most of the 21.6 million active users of BeReal log on at the appointed time and take their “silly little” BeReals of their “silly little jobs” (Figure 1) (Curry 2022; Kaplan 2022b), or as sourced from the expert crowd-sourced opinion of my group chat, we collectively log on “everyday at 4:00 pm doing the same shit” (Figure 2). Not only does BeReal unveil the “monotony of daily living” as anonymous group chat member 1 notes, but more specifically, it reveals the daily monotony of work. The collision of labor and BeReal is evident to the HR and legal departments of major companies, who, as BeReal has exploded in popularity, have sent out missives to their cool, young employees to not post BeReals revealing sensitive or classified work information (Grant 2022).

This essay explores how office or knowledge work is performed on BeReal. Critically examining work, of course, requires applying the timeless framework of Marxism. The framework of Marxism tells us that in a capitalist economy the labor and productive capacity of workers is exploited to enrich the bourgeois; in short, those who went to Brown sans student loans (Mylod 2022). According to Marxist theory, the only way to alter these structural exploitative conditions is through the articulation of class-consciousness and mass mobilization of workers from all occupations, also known as the proletariat. And even though we’re not in Karl Marx’s grim pre-digital 19th century, thinking about how users perform work on BeReal gets at one of the most pressing questions we’re confronting in today’s platformed digital economy: the increasingly visible, dismal reality of a new stage of contemporary “cognitive capitalism” dominated by knowledge work (Moulier-Boutang 2011; Wark 2015). In short, this refers to our contemporary labor market where workers are producing ideas, information, or services instead of physical products. We’ve switched the factory floor for the Zoom grid, and the BeReal app.

BeReal situates itself as an anti-curation platform that seeks to re-establish a sense of authenticity among its users, now a stark contrast to the conspicuous curation, and labor, involved in creating and posting content on other platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and Tik Tok. Feeds are dominated by everyday, banal images, often images of users at work or working. While on other platforms occasionally we’d get a glimpse of a friend or follower’s working life, possibly related to some type of career milestone like a promotion, work was never central to the content circulated on Facebook or Instagram. Legacy social media platforms like Facebook or Instagram, have, in their founding at least, emphasized content related to friends, family, and now influencers, who produce content that invites followers into a “one-way friendship” or parasocial relationship, masking the reality that influencing is increasingly a “real” job (Daniels 2021). Conversely, BeReal instead invites work directly into our feed.

Part of the incredible popularity of BeReal among younger millennial and Gen Z users relates to the centrality of work on the platform, particularly for a generation of workers who increasingly are missing out on the experience of the office entirely as a result of the shift towards remote-work modalities spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic. Enter the societal trend of “romanticizing the office” where TikTokers curate videos of their morning commutes and sexy (not sad!) salads at their desks (Solis 2022). But even with the fresh fetishization of the office, structurally speaking, parts of the labor market are increasingly moving towards remote, or at least hybrid work arrangements, where white-collar knowledge work is happening digitally. BeReal offers its users a window into the realities of this new type of labor, particularly the performative aspects of knowledge work that coincide with the performative quality of other social media content production.

On BeReal, we’re not supposed to be mugging for the camera, but with each 4:00 pm shot, we’re performing our jobs for an audience. Helen Anne Peterson presciently talked about this impulse as “LARPing” (2019), or live-action-role-playing, our jobs before the pandemic, where for workers doing knowledge-based labor, which doesn’t always unfold in strict hourly or shift increments, we feel pressured to appear like we’re working more so than actually working for our co-workers and our boss. Whether that’s being over-active on Slack, timing our emails to send at 8:37 pm, or staying late for no discernable purpose. We might not have an IRL office audience anymore, but BeReal invites us to perform our job for a more benign crowd; our friends, and it’s a performance of labor, nonetheless.

For a generation of workers chained to their desks home alone, with diminishing prospects for upward economic mobility compared to their Gen X or Boomer parents (Hout 2019) , there is something comforting in performing our jobs for our friends, if only to darkly rejoice in a sense of shared camaraderie of withering away in a late-stage capitalistic hellscape (Figure 3). BeReal takes aim at the insidious fiction other social media platforms are built upon—that everyone else is having a better time than you, is prettier than you, and richer than you. These fictions are made possible through the strategic visual curation of our Instagram feeds or Tik Tok grids that only show the highlights of our lives; the girls’ trip to Mexico but not the weeks before sitting in a dingy home office typing away. For every fun or aspirational BeReal that shows up in our feeds, more often we’re getting the comforting answer to the question that no, everyone else is not prettier, richer, or having more fun than you, they’re also sitting at home on a random Wednesday at 2:38 pm wearing blue-light glasses responding to emails from their boss who doesn’t use enough exclamation points.

Of course, this form of shared solidarity created through a prosaic set of BeReals doesn’t include an important category of workers who continue to do material, in-person labor; those working in various sectors of service industries. This set of workers doesn’t need to perform their job in the panopticon of BeReal, increasingly in-person service workers are surveilled by other emergent technologies like movement trackers or the old-fashioned security camera (Ashworth 2022). Of course, big corporations are interested in applying these same tracking techniques to remote knowledge workers, albeit through digital means (creepily logging keystrokes etc.) (Leonhardt 2022), but this development is hardly complete.

It’s in this interim period where BeReal has hit the market to great success. BeReal is unique among social media platforms in so far as it commodifies the daily indignities and miseries of knowledge work into a neat and tidy visual product, promoting a sense of community for a salaried set of informational workers, a group who has been slower to turn towards union organizing than their counterparts in service industries, as we’ve seen through the explosion of labor activism led by Starbucks baristas and Amazon workers (Hsu 2022; Kaplan 2022a). The shift towards an embrace of labor politics is slowly coming, we’ve seen academics strike at the New School and journalists in the media industry walk-out from the New York Times (Adegbesan 2022; Bansinath 2022), but we’re not there yet.

While BeReal lets us commodify the performance of our labor in a way that feels fun, might our consumption of these performances lay the groundwork for a nascent class-consciousness among a new generation and class of workers? BeReal, unlike other platforms, leans less into the social networking aspect built into the structures of Instagram, Tik Tok, or Facebook which invites you to friend or follow accounts you don’t personally know and start commenting. The critical charm of BeReal is to see what your friends are doing behind the scenes of their curated digital presence. Despite BeReal’s lack of platformed affordances for deeper communication and connection, through its invitation of user-produced content about the monotony and camaraderie of work it possesses a uniquely revolutionary potential. After all, workers of the world, as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels said: UNITE, we have nothing to lose but our followers (Marx and Engels 1969).

Image Credits

- Sourced from Juliana Kaplan’s Business Insider article.

- Author’s screenshot.

- Author’s screenshot.

References

Adegbesan, Angel. 2022. “NY Times Staffers Become News With First Walkout in Four Decades.” Bloomberg.Com, December 8, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-12-08/ny-times-nyt-strike-for-pay-benefits-is-first-in-40-years.

Ashworth, Boone. 2022. “Amazon Watches Its Workers and Waits for Them to Fail.” Wired, June 4, 2022. https://www.wired.com/story/amazon-worker-tracking-details-revealed/.

Bansinath, Bindu. 2022. “‘I’m Just Trying to Keep the Lights On.’” The Cut, December 12, 2022. https://www.thecut.com/2022/12/new-school-strike-faculty-interview.html.

Curry, David. 2022. “BeReal Revenue and Usage Statistics (2022).” Business of Apps. August 2, 2022. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/bereal-statistics/.

Daniels, Nicole. 2021. “Do You Feel You’re Friends With Celebrities or Influencers You Follow Online?” The New York Times, May 13, 2021, sec. The Learning Network. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/13/learning/do-you-feel-youre-friends-with-celebrities-or-influencers-you-follow-online.html.

Grant, Kirsty. 2022. “BeReal: Can My Post Get Me in Trouble at Work?” BBC News, September 7, 2022, sec. Newsbeat. https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-62795955.

Guinness, Emma. 2022. “Woman’s BeReal Notification Comes at the Worst Possible Time during Gynecologist Visit.” Tyla. September 2, 2022. https://www.tyla.com/life/bereal-woman-gynecologist-appointment-20220902.

Herrman, John. 2022. “This New Social App Is Boring, in a Good Way.” The New York Times, May 10, 2022, sec. Style. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/10/style/bereal-app-social-media.html.

Hout, Michael. 2019. “The Poverty and Inequality Report.” Stanford, CA: Stanford University. https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/Pathways_SOTU_2019_SocialMobility.pdf.

Hsu, Andrea. 2022. “Starbucks Workers Have Unionized at Record Speed; Many Fear Retaliation Now.” NPR, October 2, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/10/02/1124680518/starbucks-union-busting-howard-schultz-nlrb.

Kaplan, Juliana. 2022a. “Amazon’s First Warehouse Union Marked the True Turning Point towards ‘real Change’ for Workers, Says a Labor-History Professor.” Business Insider, May 22, 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-union-created-real-change-for-american-workers-movement-2022-5.

Kaplan, Juliana. 2022b. “2 Years of Pandemic, War, and Climate Crisis Have Made Many Americans Rethink Work as Just ‘Silly Little Jobs.’” Business Insider, August 21, 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/silly-little-jobs-pandemic-war-climate-change-great-resignation-antiwork-2022-8.

Leonhardt, David. 2022. “You’re Being Watched.” The New York Times, August 15, 2022, sec. Briefing. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/15/briefing/workers-tracking-productivity-employers.html.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 1969. “Manifesto of the Communist Party.” In Marx/Engels Selected Works, translated by Samuel Moore, 1:98–137. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Moulier-Boutang, Yann. 2011. Cognitive Capitalism. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Mylod, Mark, dir. 2022. The Menu. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wNBwrDGZ4-k.

Petersen, Anne Helen. 2019. “LARPing Your Job.” Substack newsletter. Culture Study (blog). May 5, 2019. https://annehelen.substack.com/p/larping-your-job.

Solis, Marie. 2022. “These Young Workers Are ‘Romanticizing’ the Return to Office – The New York Times.” The New York Times, November 27, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/27/business/tiktok-office-influencers.html.

Wark, McKenzie. 2015. “Cognitive Capitalism.” Public Seminar (blog). February 19, 2015. http://www.publicseminar.org/2015/02/cog-cap/.

The critical charm of BeReal is to see what your friends are doing behind the scenes of their curated digital presence.