Everyone Stop What You’re Doing, And be Real: Conceptualizing BeReal as a Live Public

Zari Taylor / University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

You’re working remotely at a local coffee shop. Waiting at the baggage carousel for your suitcase to arrive at the airport. Attending the funeral of a loved one. Standing in line at the bank. Suddenly, your phone pings with an all too familiar notification. It’s time to BeReal.

As you assume the position to snap a picture, you notice that others around you are doing the same. A group of friends cluster together at their table, mugs in hand. A son attempts to convince his dad to smile for a selfie. A teen takes a not-so-discreet picture from their pew in the church. Collectively, you all rush to meet the two minute deadline. No matter the setting, you’re all answering the call, capturing whatever you’re doing when BeReal asks.

No activity or environment appears off limits. Whether you’re fresh out the shower, on a date, crying after a breakup, at a sporting event, or being held hostage during a bank robbery (according to a Saturday Night Live skit), there’s never a wrong time to be real – because everyone else is doing it too.

This moment of collective capture is brought to you daily by BeReal, the social media app co-founded in Paris, France by Alex Barreyat and Kévin Perreau in December of 2019. The BeReal app has been downloaded 27.9 million times as of June 2022 with the majority of the downloads happening between then and June 2021. By March 2021, BeReal had become one of the top 10 social media apps in France and a year later became popular on American college campuses. With 21.6 million monthly active users and 2.93 million users accessing the app daily, it’s safe to say that BeReal is having a moment.

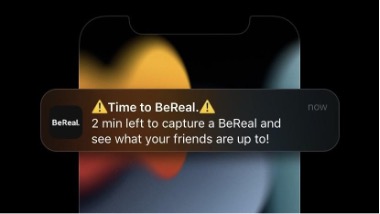

The frenzy is confounding given how elementary the app is. According to its website, BeReal is “a new and unique way to discover who your friends really are in their daily life.” The premise is simple. Everyday, the app sends out a notification to users that it’s “Time to Be Real.” Users then have two minutes to post a picture with both their front- and back-facing cameras. Users can choose to post to their friends feed or to a global feed. Through its simplicity, BeReal’s model contrasts with other popular social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and TikTok, and thus offers an opportunity to participate in new forms of online sociality.

For decades, social media scholars have considered how social networking sites enable different forms of being yourself and interacting with others online. José Van Dijck (2013) offers the concept of “platformed sociality” to describe how social media platforms mediate social activities. She maintains that the internet allows individuals to organize their lives on varying social levels. Although this organization looks different on each platform, most share a number of core features that animate and interweave their online and offline lives. Platforms compete for user attention, and essentially meet their own commercial interests, by offering interesting and new forms of online sociality. As new platforms emerge on the market, they make a name for themselves by doing the same thing as everyone else, but with a twist.

So how can we pin down the type of sociality that has popularized BeReal? We need to understand its affordances. Jenny Davis (2020) and others explain that affordances do not dictate behavior but encourage, constrain, and enable them. Taina Bucher and Anne Helmond (2017) join her in echoing the utility of affordance theory, but focus on the affordances of social media platforms which they locate as sites of meaning making and possible action. Twitter’s 2015 change from a “favorite” to a “like” button, for example, transformed the implied meaning of the action. As Bucher and Helmond found, Twitter users preferred the “favorite” feature because it was more “neutral” than the “like,” meaning that even minor tweaks can afford distinct possibilities and interpretations. Twitter and other platforms include these features and others, like commenting, friending, and posting. Users navigate affordances in their everyday usage by either appropriating or rejecting the assumed norms and affordances of the platform. Further, these features and their affordances can be taken for granted as they become quotidian.

Examining a platform’s affordances requires slowing down and connecting user experience to technical characteristics often overlooked. Ben Light, Jean Burgess, and Stefanie Duguay (2018) developed the Walkthrough method to critically analyze apps. The method is grounded in both Science and Technology Studies and Cultural Studies and allows researchers to establish an app’s intended purpose through a critical analysis of their characteristics. Such characteristics include the user interface arrangement, the functions and features that mandate activities, the textual content and tone, and symbolic representations related to color or font. These are the details that users may or may not even make conscious note of, but they have a profound impact at any stage of use.

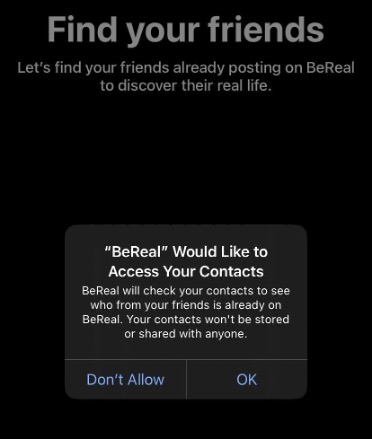

An analysis of Bereal’s app infrastructure demonstrates what kind of experience users are intended to have. While the app has numerous functionalities and features shared amongst other popular social media apps, several mark it as unique: emphasis on local community, timed spontaneity, public tardiness, and contingent access. Like many platforms, users are encouraged to sync their contacts to jumpstart their friends lists. This allows the app to capture the activity of your offline friend groups, as well as connecting you to the global community of users.

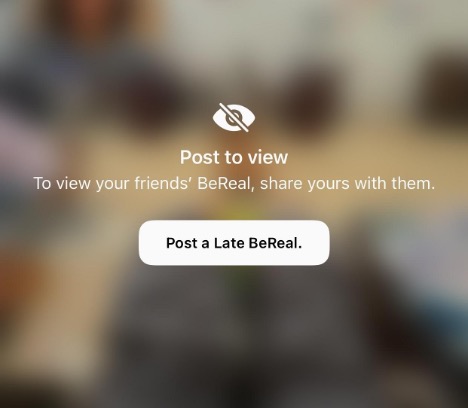

BeReal’s intended use is also tied to specific and sporadic timing. If all users answer the call of the daily notification, they would only need to use the app once a day to see what everyone is up to in the two minutes the app allots. The time differs everyday and fosters the app’s claim to authenticity – not granting users time to find the best lighting or throw on makeup. This emphasis on non-curated content puts users in a position to participate as expected, or choose to be late. If they choose the latter, everyone will know because the app’s default notifications make users aware who has posted after the intended time and posts are labeled with how many minutes or hours late a post is. Public tardiness lets everyone know that the latecomer was not being real, or rather real enough. Additionally, users have to post in order to see the posts of others, making their access continent on participation. Everyone has to equally opt in for the app to work.

BeReal offers a form of online sociality that can be described as a live public. While other social media platforms allow for users to engage with a public at any time, BeReal’s facilitation is determined by the time their alert is sent. The purpose of the app is to bring users together at a particular time, allowing them to share what they are doing, as well as reacting to the captured moments of others. This combines danah boyd’s (2011) concept of a networked public wherein traditional publics are restructured by networked technologies, and the concept of liveness which contends with assumptions that media offers true representations of social reality (Feuer 1983). In particular, it is akin to Nick Couldry’s (2004) “online liveness” where the internet mediates a shared social reality. BeReal mediates online liveness for users within both a local and global community. Their intention is to let us know what our friend 1 mile away is doing while also showing what a stranger 100,000 miles away is doing. This public is structured by internet technology and happens simultaneously.

It could be questioned whether the BeReal model is sustainable or simply a phase, but it’s already been adopted by others. In August 2022, Instagram introduced a dual camera feature for Android and Iphone users, allowing users to take photos and videos with both the front- and back-facing camera. A month later, TikTok introduced “TikTok Now” which they describe as a “daily photo and video experience to share your most authentic moments with the people who matter the most”. TikTok markets the new features as a tool for “authentic” and “spontaneous” connections, tapping into the elements of temporality and realness that BeReal does. Though the company maintains that the feature remains in its experimental phase, BeReal’s influence is clear.

These duplications by giants in the social media industry demonstrate how niche online sociality is capitalized on and competed over. It also highlights the practical importance in theorizing about the new form of online sociality that BeReal provides and the potential growth for live publics across platforms. BeReal prompts us to stop everything and be real with ourselves, our friends, and the world – and it seems that we’re all taking them up on their offer.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1: The daily BeReal notification. Author’s screen grab.

- Figure 2: Screengrab from registration. BeReal allows users to sync their contacts to find friends. Author’s screen grab.

- Figure 3: Users must participate to gain access. Author’s screen grab.

boyd, danah. “Social networks as networked publics: affordances, dynamics, and implications.” In A Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites edited by Zizi Papacharissi, 39–58. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Couldry, Nick. “Liveness, “Reality/’ and the Mediated Habitus from Television to the Mobile Phone.” The Communication Review 7 (2004):353-361. DOI: 10.1080/10714420490886952

Davis, Jenny L.. How Artifacts Afford: The Power and Politics of Everyday Things. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. 2020.

Feuer, Jane. “The Concept of Live Television: Ontology as Ideology” In Regarding Television: Critical Approaches edited by E. Ann Kaplan, 12-22. University Publications of America, 1983.

Light, Ben, Jean Burgess, and Stefanie Duguay. “The walkthrough method: an approach to the study of apps”. New Media & Society 20, no. 3 (2018): 881–900.

Van Dijck, José. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.