BeReal now: Digital temporal authenticity on BeReal

Tim Highfield / University of Sheffield

Much of the attention given to BeReal, including the framing for this special issue, is around the relationship between the app and authenticity; after all, reconsidering the ‘real’ is a key part of the app’s discourse, from its name down to its promotional language offering a “new and unique way to discover who your friends really are in their daily life”.

As Brooke Erin Duffy and Ysabel Gerrard (2022) note, authenticity in its various forms has been a goal of many social platforms past and present, albeit one which can then get subsumed by new user practices and cultures, platform affordances, and the goals and business models of the platforms themselves. In this regard, BeReal is just the latest in a long line of online spaces aimed at presenting a real and authentic self. However, where I want to focus in this piece is less on visual or aesthetic representations and interpretations of authenticity. Instead, I am interested in BeReal and its treatment of temporal authenticity, and how this relates to other digital framings of time and temporality.

In my current research, I’m exploring digital time from two aspects: as both a critical motivator for user engagement and as setting specific conditions for working with digital platforms. For many popular platforms, a multitude of temporalities exist, shaped by platform architecture, design, and affordances. On Instagram, for example, there are different temporalities at play. These include the feed – ordered not chronologically, but algorithmically, with recent posts presented in relation to the current moment (two minutes ago, three hours ago, six days ago). Juxtaposed with the implied permanence of the feed, meanwhile, is the ephemerality of Stories. Culturally, too, Instagram has its own temporal considerations. In the early years of the platform, engaging in the moment with events and experiences by posting instantaneously was a prevalent norm of use, to the point where posts not reflecting what was happening right now were denoted with a #latergram hashtag. This evolved extensively over time, and now there is a far more curated perception of how and when Instagram users share to their feeds – a perception to which BeReal is positioned as an alternative or an antidote (Hawley, 2022).

Temporally, BeReal seems to harken back to the idealisation of an earlier spirit of social media platforms, where sharing the banal and everyday – tweeting about your lunch, posting a photo of your coffee – were regular rituals, before the spaces and users became monetised and took on greater political significance. Rather than heavily constructed and planned content, BeReal is predicated upon the communal and immediate experience of ‘now’: no matter who you are, the same ‘time to BeReal’ prompts users to share their current situation.

The importance of the present is a common feature of digital platforms; in a special journal issue focused on ‘mediating presents’, editors Rebecca Coleman and Susanna Paasonen (2020) underline “the significance of a present or ‘now’ temporality” to how digital media function, how they are produced, experienced and conceptualised” (p. 2). However, where Coleman’s (2020) research has explored how digital platforms’ considerations of ‘now’ are perceived by users as “real-time, liveness, instantaneous and always-on”, BeReal is not entirely aligned with these ideas. Unlike the ‘now’ of Instagram, for example, which is constantly updated in relation to when the user opens the app, BeReal is temporally situated in the specific moment of when it is ‘time to BeReal’: any delayed posts are presented as being however many minutes or hours late. Similarly, unlike the ‘always-on’ nature of TikTok, Twitter, or Snapchat (among many others), where a user may post at any moment, BeReal only offers a single daily ‘now’.

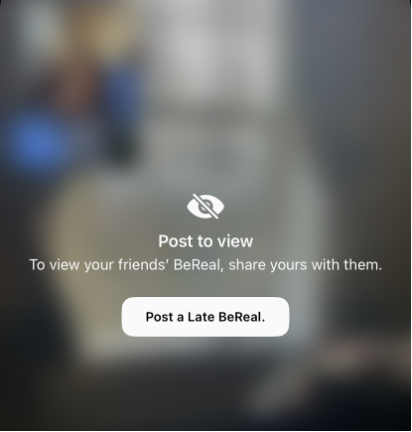

In this sense, BeReal represents a move away from algorithmic orderings of time, or what Taina Bucher (2020) describes as ‘right-time’ rather than ‘real-time’ media, to a situation more akin to “an experience of a shared ‘now’ instigated by the temporal regime of the medium” (p. 1711). The user has no control over when it is ‘time to BeReal’, just about when they choose to engage with it – and if they want to see others’ content, they have to engage. In return, time takes precedence over other metrics that shape user experiences on other platforms. While gamified in how users are pushed to engage, BeReal is not beholden to measures of interaction and financial contributions that can impact the visibility of content.

see other users’ content

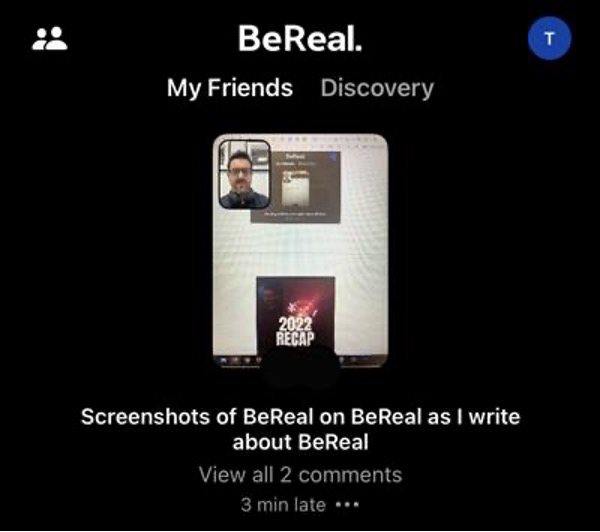

This minimalistic rendering of time extends to how archival content is treated on BeReal. Previous days’ posts are moved to memories that are only accessible to the posting user: anything another user posted on a day other than today is not visible, and personal archives also lack any supplementary information (e.g. reactions and comments) that in other spaces would be incorporated into the datafication of the user. Compare this approach with, for example, Facebook’s Memories feature that uses metrics like interactions to determine which content should be resurfaced one or several years later (see, e.g., Annabell, 2022, p. 1545). Even in BeReal’s 2022 version of the ‘year in review’ repackaging of user data (best exemplified by Spotify Wrapped), the resulting recap was simply a video playing through each post in quick succession. The recaps reframed the daily within the sum of an individual user’s output, rather than offering, for example, unclear and imprecise reinterpretations of user actions as reflective of different personality types. In doing so, rather than trying to highlight the exceptional or unusual, the recaps offered a different twist on Wendy Chun’s (2016) examination of digital technologies: the videos demonstrated recurring patterns in peoples’ lives through what they posted, how they were updating but remaining the same. In this way, BeReal has a clear point of distinction with more curated feeds on platforms that put value on new and different content.

What this suggests – at least in terms of how BeReal positions its ideal or expected user – is that a sense of temporal authenticity underpins what gets posted: that this is a true and accurate depiction of what the user is doing, at the moment specified by BeReal (and that the user is able – and willing – to post at any moment). This approach treats the mundane and the extraordinary as equally worthy of documentation: you do not know what other users will post, just that they are ostensibly doing it now, and this surprise of the unknown is part of BeReal’s appeal. The prompts do not fit snugly into the rhythms of everyday life or of other platforms. By prompts being random, BeReal is deliberately arrhythmic, something which can also push against other elements of ‘always on’ media as there is not constantly new content to see or infinite posts to scroll through. Of course, this is not necessarily how the user treats the platform. Curation can still happen both through how a user visually frames their post and whether or not they engage with the two minute window to post ‘on time’; there can be a trade-off of the ‘cost’ of posting late with having something different or more interesting to post (see, e.g., Tiffany, 2022).

This framing of time on BeReal allows for a different consideration of the conditions set by digital platforms and the cultures and practices that subsequently develop. BeReal offers its own form of mediated ritual. Not only does it privilege the mundane (and thus bestow value on everyday acts rather than just on the extraordinary or exceptional – see Trillò et al., 2022) but the capture of each daily post becomes ritualised, as described by Boffone (2022). While this fits into a longer history of ritualised media use, what sets the case of BeReal apart is that this is highly structured and prescribed: ultimately, BeReal’s time is set by the platform. Users cannot change this, but just how they engage with it.

The current moment of BeReal – for how long it may last in this form – gives us the opportunity to reflect more broadly on the temporal and cultural dynamics of digital platforms. BeReal can provoke new ideas about mediated moments and events, in valuing equally fleeting depictions of events both unusual and banal. These considerations can be compared with how previous technologies have generated similar discussions, putting BeReal within a longer history of the mediation of everyday life. At the same time, the growth in popularity of BeReal in 2022 also allows a way in to understanding how innovation and change happens within digital technologies, with rival platforms such as TikTok and Instagram attempting to build their own, similar features. By itself, BeReal demonstrates a particular temporal intervention by digital technology into everyday life. The next point of interest, though, is whether this represents a move away from the temporal regimes promoted through other platforms, or if the time to BeReal is ultimately incorporated into these platforms’ existing temporalities.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1: Screenshot of BeReal showing a post submitted 16 hours late. Author’s screen grab.

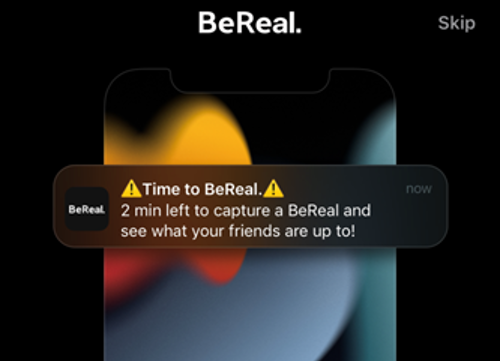

- Figure 2: Screenshot of BeReal promotional material showing the ‘Time to BeReal’ prompt. Author’s screen grab.

- Figure 3: Screenshot of BeReal of prompt asking the user to post a ‘late’ BeReal in order to see other users’ content. Author’s screen grab.

- Figure 4: Screenshot of BeReal 2022 recap video. Author’s screen grab.

- Figure 5: Screenshot of BeReal post uploaded 3 minutes late. Author’s screen grab.

Annabell, T. (2022). ‘Sharing for the memories’: Contemporary conceptualizations of memories by young women. Memory Studies, 15(6), 1544-1556. https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980221133729

BeReal. (n.d.). BeReal. Your Friends for Real. Retrieved 13 January 2023, from https://bere.al/en

Boffone, T. (2022, September 29). You Better Be Quick When It’s Time to BeReal. PopMatters. https://www.popmatters.com/bereal-social-media-gamification

Bucher, T. (2020). The right-time web: Theorizing the kairologic of algorithmic media. New Media & Society, 22(9), 1699–1714. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820913560

Chun, W. H. K. (2016). Updating To Remain The Same: Habitual new media. The MIT Press.

Coleman, R. (2020). Making, managing and experiencing ‘the now’: Digital media and the compression and pacing of ‘real-time’. New Media & Society, 22(9), 1680–1698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820914871

Coleman, R., & Paasonen, S. (2020). Mediating Presents. Media Theory, 4(2), 01–10.

Duffy, B. E., & Gerrard, Y. (2022). BeReal and the Doomed Quest for Online Authenticity. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/bereal-doomed-online-authenticity/

Hawley, R. E. (2022, May 13). BeReal and the Fantasy of an Authentic Online Life. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/rabbit-holes/bereal-and-the-fantasy-of-an-authentic-online-life

Leaver, T., Highfield, T., & Abidin, C. (2020). Instagram: Visual social media cultures. Polity.

Tiffany, K. (2022, August 1). No, I Will Not BeReal. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/08/bereal-app-authenticity-social-media-instagram/671012/

Trillò, T., Hallinan, B., & Shifman, L. (2022). A typology of social media rituals. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 27(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac011