Time to Be Real?: Nostalgia, Authenticity, and the Digital Return to the Everyday

Jasmine Banks, Mel Monier, and Olivia Stowell / University of Michigan

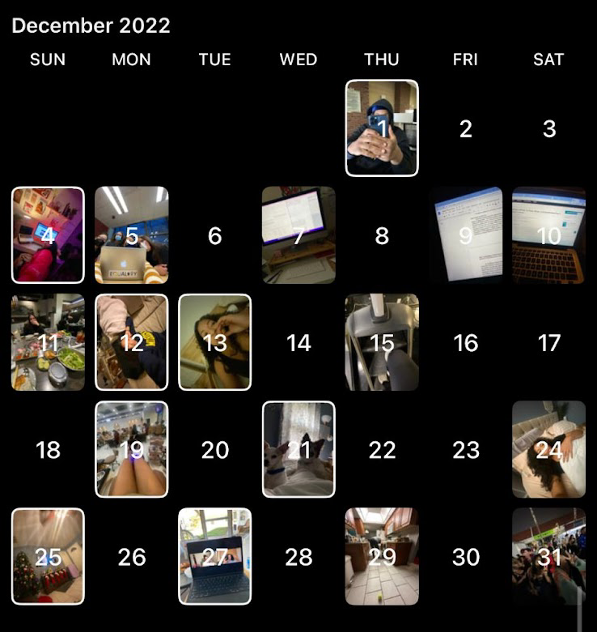

Walking across campus to our evening class, we each receive a notification. Our pockets collectively buzz, alerting us that “it’s time to ‘BeReal.’” Frozen like statues, everyone around us is taking photos at the same time. Ignited by a notification from the social media app BeReal, scenes like this take place every day. In its push for users to expose everyday moments from their lives, BeReal offers an incitement to digital authenticity. Once a day at a random time, all users receive a prompt to take a photo using the front- and back-facing phone cameras simultaneously. Each day’s photo is archived to a private calendar, which functions as a digital diary [see fig. 1]. We are reminded of our childhood Scholastic Book Fair diaries with locks and keys, of the Password Journal from the early aughts—the pleasure of writing things that no one else would ever see. BeReal follows a similar function to these earlier diaristic forms, but with a key difference: the diary is now public.

In this essay, we explore how BeReal offers a nostalgic return to the “authenticity” of early social media platforms and an incitement to realness, while also functioning as a public display of intimate everydayness. Merging the “authentic” with the “mundane” in public, BeReal satisfies seemingly divergent desires for “realness” and “performance” in online spaces, providing an alternative to the hyper-curated feeds of other platforms through its seamless synthesis of the public and the private. Through its particular affordances, such as the unpredictability of the “Time to BeReal” notification, the lack of algorithmic boosting, and the absence of sharing/reposting features, BeReal raises the question of whether it is possible to achieve authenticity in the digital world, and what privacy we might give up to do so.

Promoted as an “anti-app,” BeReal offers itself as a solution to “social media fakery” (Duffy, 2022). BeReal entered the industry during a time of collective fatigue. Being yourself—being real—in the digital is tiring. The feelings of exhaustion and disappointment from endless social media use create what Tung-Hui Hu terms digital lethargy (2022): a pervasive sense of listlessness, dissociation, and passivity that emerges from contemporary pressures to be always connected, always productive. Digital lethargy also arises from the expectation to properly perform authenticity in digital spaces. In its more spontaneous digital mode, BeReal aims to challenge the need to present a polished version of oneself online. By instead offering a filterless, minimalistic interface, BeReal allows users to connect with others without feeling the pressure to perform a curated version of themselves.

Most social media platforms hail users to present the most polished versions of themselves by offering in-app filters, encouraging the use of editing tools, and foregrounding the construction of “aesthetics.” On Instagram and TikTok, there is an implicit expectation to be “aesthetic,” to share content that is visually appealing to cultivate a perfectly manicured feed.

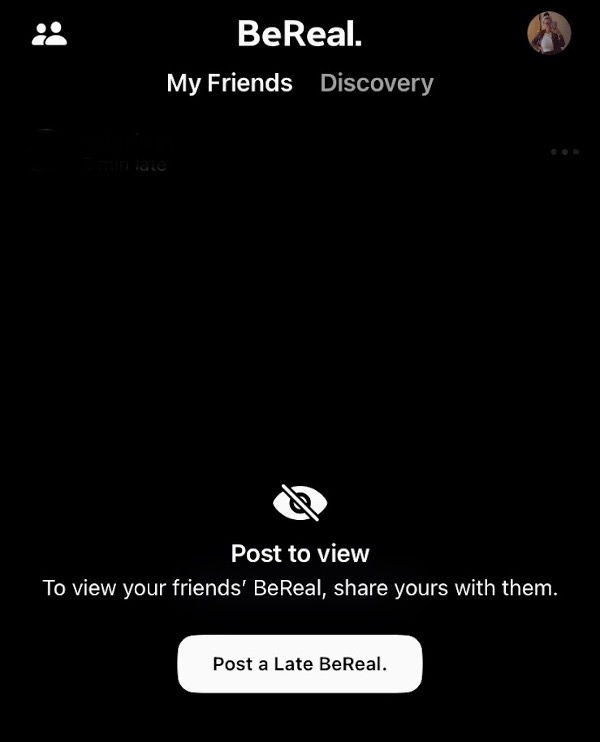

In contrast, BeReal appears to offer a place to escape curated performances of the digital self, providing users somewhere to post without any incentive or expectation to be anything other than themselves. BeReal’s supposed “effortlessness” reflects our desire for ease in the digital. But some features in the app, such as users’ inability to see others’ posts until they post themselves [see fig. 2] and the app’s notifications calling out users who post late to their friends, operate as a sort of social norm-enforcement (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955) encouraging users to follow certain rules or guidelines to comply with the majority, to use the platform in particular ways that may not offer as much of an escape from performativity as we thought.

While BeReal may promote a form of self-discipline, it also grants users a level of “realness” that has made the app so popular, with over 53 million installs (Perez, 2022). The rise of BeReal marks a cultural and digital shift, a desire to return to “simpler,” “realer” times. BeReals are casual, often blurry, unfocused moments, with bad lighting and bad angles [see fig. 3] depicting the everyday and the mundane. BeReal’s affordances speak to users’ desire for nostalgia by offering a more “authentic” approach to social media, and its lack of algorithmically driven content is refreshingly reminiscent of the chronological feeds of early social media. While there may not be user desire to return to black and white photos of train tracks and Starbucks drinks characteristic of the early days of Instagram, or the oversaturated selfies and lengthy rants endemic to 2000s-era MySpace and Facebook, there does appear to be a nostalgic desire to revisit other features of early social media, particularly using social media to document daily experiences, like three friends excitedly eating Korean BBQ.

Furthermore, unlike other platforms, BeReal’s algorithm does not appear to be driven by engagement. There is no algorithmic reward for participating; engagement with posts does not push content farther up the feed or increase visibility. Consequently, there is also less self-promotion—there is currently no way to become “BeReal famous.” Content is organized by the time it was posted, with the assumption that the feed comes alive as everyone posts around the same time. BeReal’s ethos of spontaneity offers users a glimpse into their friends’ everyday lives, promising users access to each other through capturing “real” everyday moments in real time. The images are expected to be unfiltered—blurry photos of friends sitting together in the living room or counting down the minutes until the work day is over. Users could be doing absolutely anything (or oftentimes nothing at all), affording a feeling of intimacy by catching snapshots of everyday moments that might not appear polished enough for the logics of other image-sharing platforms. These snapshots capture the seemingly mundane and boring, but ultimately suggest a presentation of users’ most authentic selves.

But why would someone volunteer to share their digital diaries with others? In addition to BeReal’s spontaneity, the platform aims to foster a sense of community. Users are encouraged to collectively participate, not only through random simultaneous daily posts, but also because the app is virtually inaccessible until the user posts [see fig. 2]. Sharing your daily BeReal unlocks the app, opening the pages of your friends’ digital diaries to view and react to as they do the same.

And yet, despite all that BeReal may appear to offer us—a salve for the manicuredness of so many digital spaces, intimacy with the everyday lives of those geographically close or far from us, a respite from the deluge of advertisements that increasingly invade and comprise the social-digital world—it is worthwhile to ask what BeReal may be asking of us, doing to us. As an emergent platform with its own logics and affordances, BeReal hails us toward not only particular behaviors, but also particular subjectivities and structures of personhood.

What Cohen and Richmond (2022) term “computational personhood” names “the structure of subjectivity that had to be invented alongside computing technology” (p. 161), encompassing how “all persons are made, eventually, to be intimately compatible with computing” (p. 159). We would argue that social media platforms like BeReal participate in constructing digital personhood, the structures of subjectivity that must be invented so that we can live within/alongside the digital. In its incitement toward spontaneous authenticity, in its bids for users to disclose their location in space at random points in time, in its construction of authenticity as a disclosure of the private, the intimate, and the mundane, BeReal imagines and enacts a digital personhood that raises thorny questions about privacy, datafication, and surveillance.

Even as BeReal offers a digital space currently free from advertisements and influencers, it is not immune from acclimating its users toward what Andrejevic (2002) calls a “subjectivity consonant with an emergent online economy” (p. 252). Though BeReal eschews the kind of relentless product placement and commercialization now part and parcel of Instagram and Facebook, we suggest that it nonetheless encourages users to participate in their own self-surveillance and in making the content of their everyday lives available in the digital world as data, presented as digitized memories. As Mbembe (2021) writes, the purpose of the transformation of everyday, intimate facets of our lives into “content” is “not only to heighten the predictability of our behavior. It is also to make life itself amenable to datafication” (p. 19).

Whether or not BeReal has any staying power as a social media platform remains to be seen. But the digital lethargy and exhaustion of digital self-performance it indexes, as well as the desires for authenticity and nostalgia that it fulfills, may prove to be more durable structures of feeling. We can’t know yet whether BeReal marks the future of social media or merely a blippy fad in the longer story of digital life—or if a platform like BeReal, where most users only engage once a day (Perez, 2022) and there are no advertisements, can even survive in our current social media landscape. But perhaps more importantly, we also have only begun to apprehend the subjectivities we must inhabit to live alongside the digital—and what “being real” may come to mean.

Image Credits

- Authors’ screenshot

- Authors’ screenshot

- Authors’ screenshot

References

Andrejevic, M. (2002). The kinder, gentler gaze of Big Brother: reality TV in the era of digital capitalism. New Media & Society, 4(2), 251-270. doi-org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/10.1177/14614440222226361.

Cohen, K., and Richmond, S. C. (2022). New histories of computational personhood. JCMS, 61(4), 158–62.

Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The journal of abnormal and social psychology, 51(3), 629.

Duffy, B. E., & Gerrard, Y. (2022, August 5). BeReal and the doomed quest for online authenticity. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/bereal-doomed-online-authenticity/.

Hu, T. (2022). Digital Lethargy: Dispatches from an Age of Disconnection. MIT Press.

Mbembe, A. (2021). Futures of life and futures of reason. Public Culture, 33(1), 11-33. doi.org/10.1215/08992363-8742136.

Perez, S. (2022, October 10). BeReal tops 53M installs, but only 9% open the app daily, estimates claim. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2022/10/10/bereal-tops-53m-installs-but-only-9-open-the-app-daily-estimates-claim/.