A Porn Studies Scholar’s Plea to Journalists

Becky Holt / Concordia University

I am using this platform to make a plea to journalists in North America: stop using online pornography as a facile means to denounce child pornography. Stop putting children at the heart of your reporting on Pornhub. For the last two years, Pornhub and its parent company MindGeek have become the focus of campaigns to tamp down child pornography and stop predators from targeting kids online. The truth is most of the websites we use daily—Facebook and YouTube, for example—have reported issues with child porn on their platforms. Yet Pornhub has been increasingly singled out as the fall-guy. Not because its issues with child porn are more severe, but because it is an easy target.

It started in 2020 when The New York Times published an opinion piece titled, “The Children of Pornhub.” In it, columnist Nicholas Kristof alleged that Pornhub was knowingly hosting and monetizing revenge porn and child pornography. Kristof claims that Pornhub makes itself seem wholesome when it is, in reality, “infested with rape videos.”[1] The article triggered public outrage; it engendered a barrage of other articles and an investigation into MindGeek by the Canadian House of Commons Ethics Committee (ETHI). Kristof is lauded by readers—“with this piece, you have done yet another important service for society,” one commenter wrote on the online version of the piece.[2] But as an adult film scholar, Kristof’s approach feels familiar, even cookie-cutter. It is a strategy to oppose pornography taken straight out of the moral panic playbook: the shout to, “save the children.”

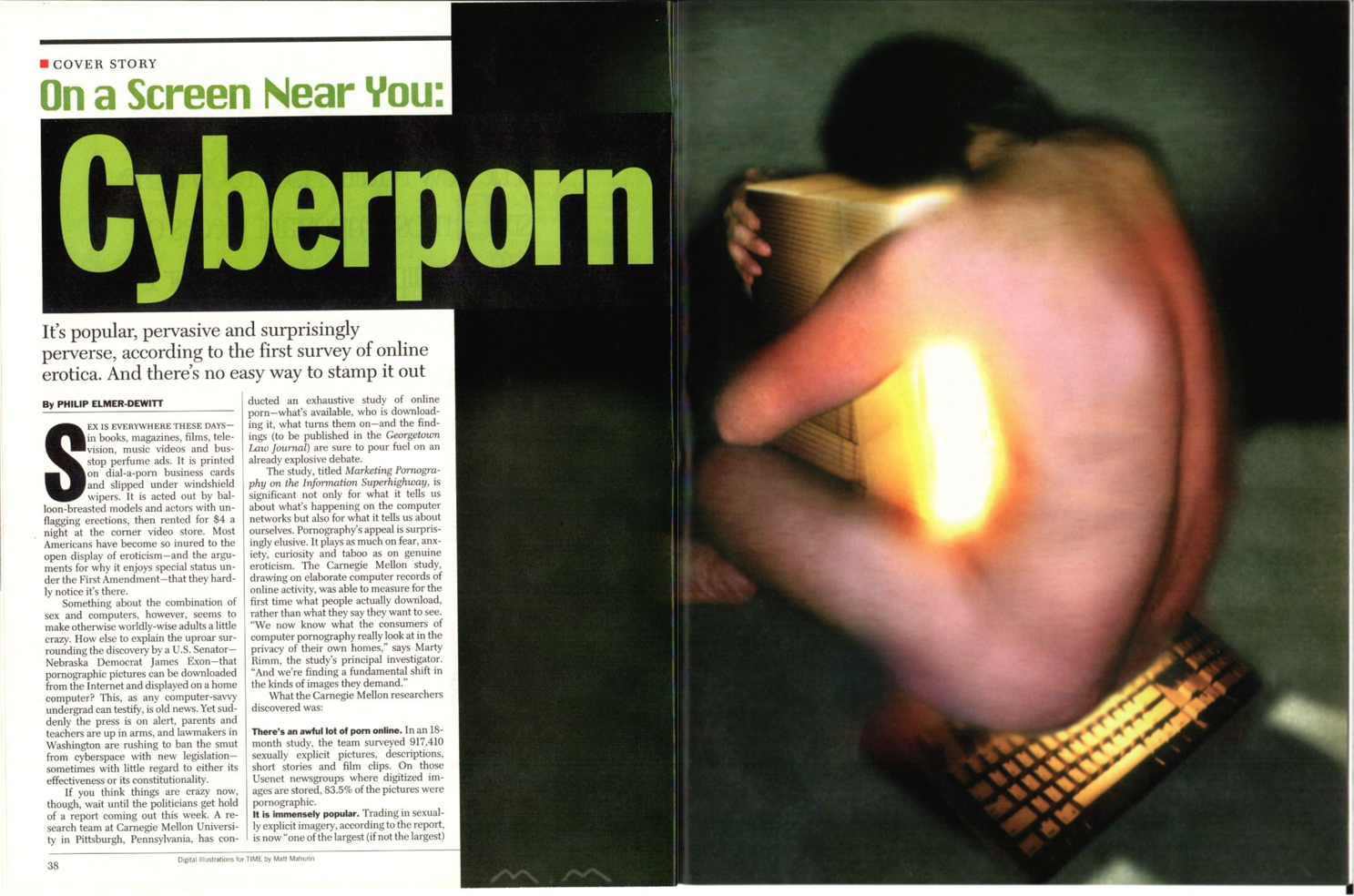

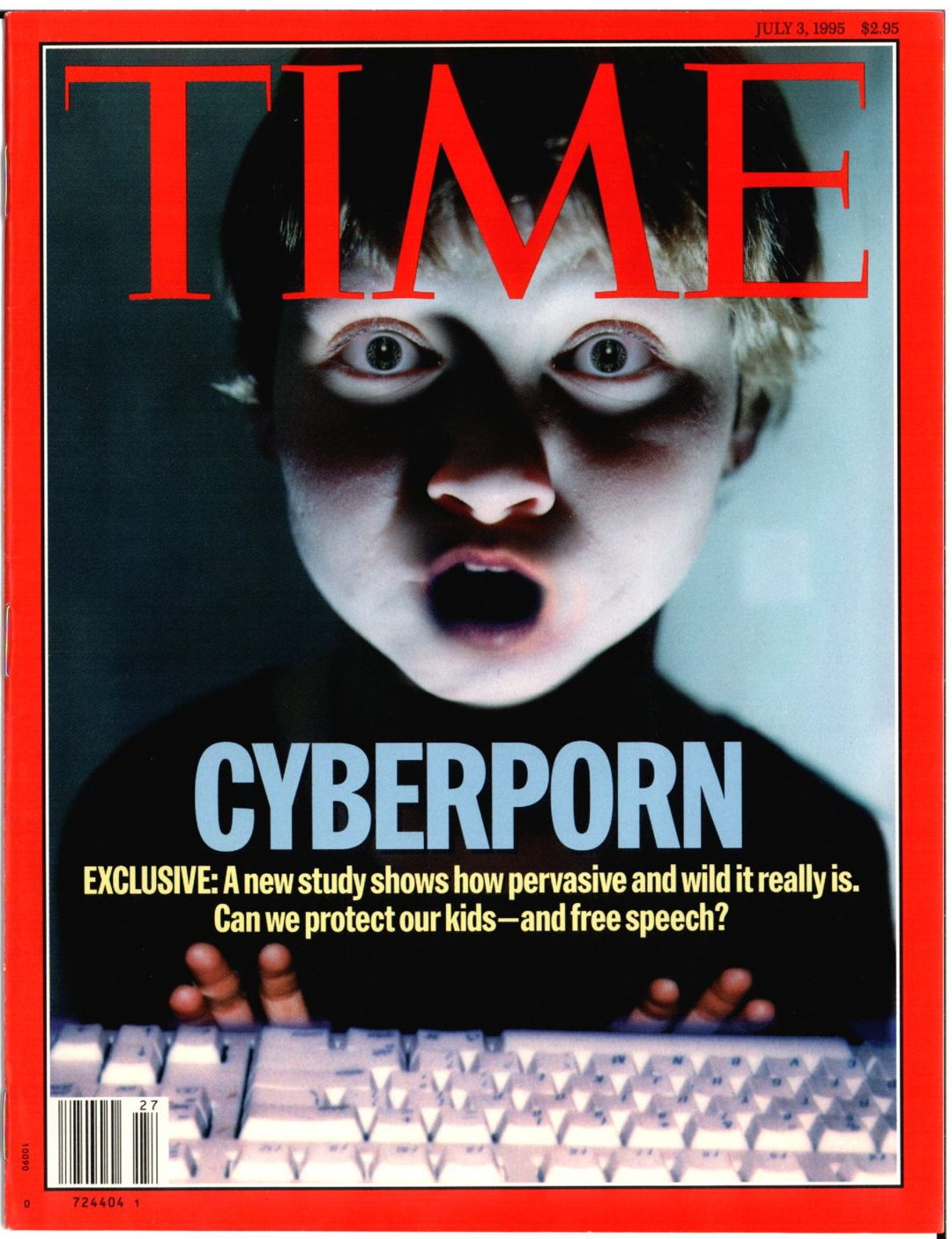

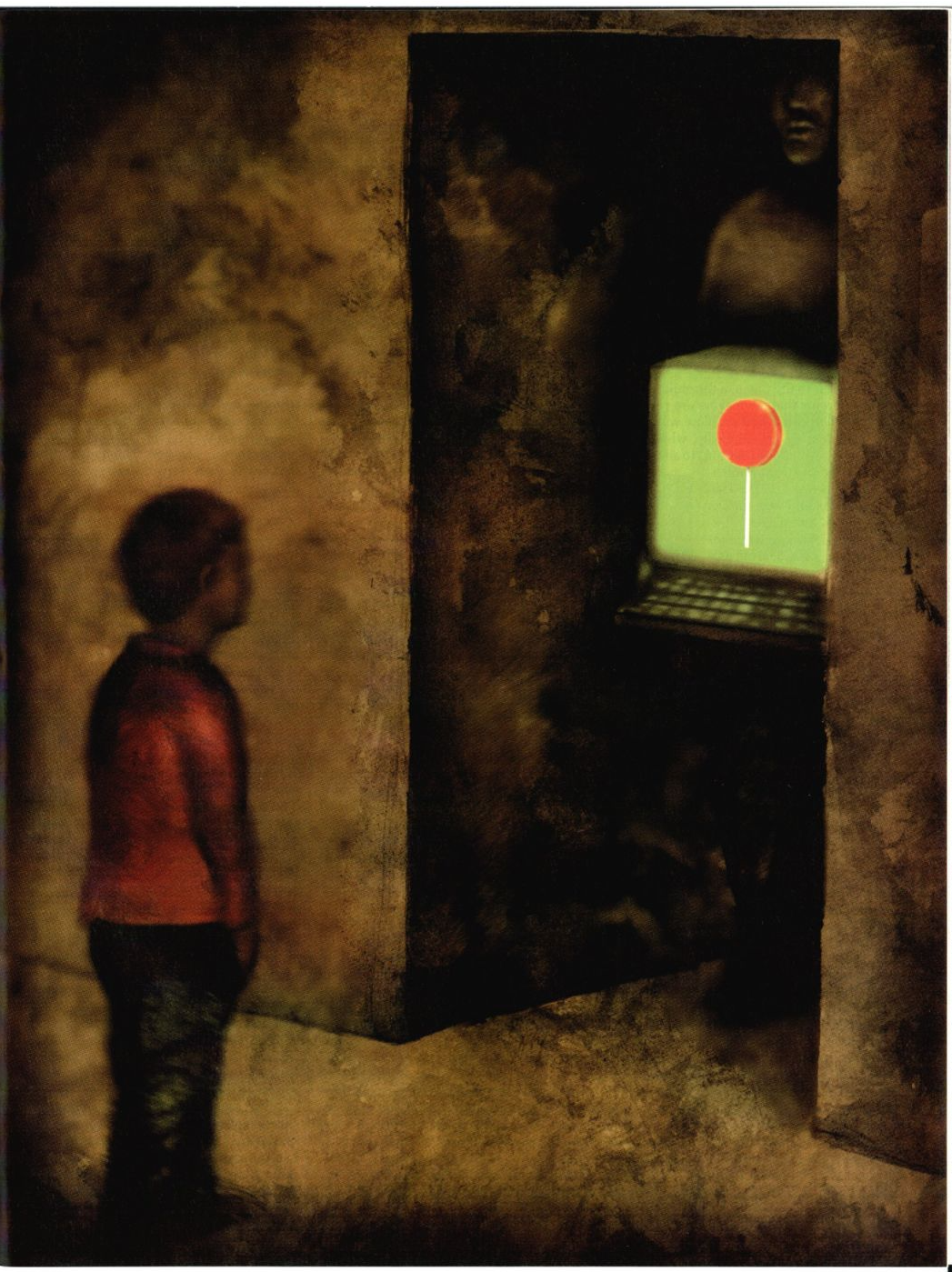

Since the 1990s, there have been surges of interest and activism concerning child pornography and child predators. Despite the rapid transformation of the Internet, each wave of concern has taken a remarkably similar form. For example, compare the images from a Time Magazine article published in the mid-90s with recent images from The Atlantic and The New York Times. In 1995, Time published a cover story titled, “On A Screen Near You: Cyberporn.” The piece was a bombshell, and even though many of the facts it presented were later debunked, it played a significant role in how readers came to view cyberporn. The issue’s cover is almost infamous: it is a stark photograph of a young boy lit by the harsh glow of a computer screen. With his mouth agape, and his fingers hovering over a keyboard, the little boy looks terrified by what he is witnessing on screen—the horrors of cyberporn. Inside the magazine, the article features a series of similarly evocative images. One of them is an illustration of a small child staring into a room lit up by a computer screen displaying a giant lollipop—a reference to predators luring children with candy—and behind it looms the terrifying outline of a predator.

Compare this to an illustration featured in The Atlantic alongside an article published in 2022 titled, “How to Fix America’s Child Pornography Crisis.” The image shows the figure of a small boy standing at the precipice of darkness; the menacing arm of an adult looms nearby, seemingly leading him into it. Similarly, Kristof’s article features close-up portraits of Serena Fleites—a young woman who fought for years to have nude videos of her at age fourteen removed from Pornhub—taken more recently at age nineteen. In the image, she looks off into the distance, fresh-faced and serious; a reminder of how young she still is. Even at a glance, the images from Time and the more recent examples are remarkably similar. Both depict situations where young vulnerable children are in danger of being preyed upon by virtual predators.

I am not the only scholar who argues that concerns for child safety often act as a distraction from other discourses. Wendy Chun, for example, argues the images and article in Time were representative of the fears we harbor about pornography more generally—“overexposure, intrusion, surveillance, and the birth of perverse desires.”[3] And that the panic concerning child pornography reveals a social and cultural proclivity to believe that emergent technologies inherently “induc[e] perversity.”[4] Other scholars such as Gillian Harkins argue that cultural representations of the pedophile, such as the ones above, have the unintended consequence of shoring up the “virtual pedophile.” An imagined predator that does more to “justify needs for biopolitical security,” and less to address real-world harms.[5]

In Opinion

— The New York Times (@nytimes) December 4, 2020

“Pornhub prides itself on being the cheery, winking face of naughty,” @NickKristof writes. “Yet there’s another side of the company: Its site is infested with rape videos.” https://t.co/u4toLxcE15

Rumors about Pornhub were circling for years before Kristof’s article, but the prestige of The New York Times forced MindGeek to act. In the article, Kristof makes three suggestions for how MindGeek could begin to address its issues with child pornography, “1.) Allow only verified users to post videos. 2.) Prohibit downloads. 3.) Increase moderation.”[6] Pornhub incorporated all of these suggestions and more, combing through the website to find illegal content, disabling downloads, and implementing a strict user-verification process that requires government issued identification. However, it is difficult to say whether or not these measures put a stop to pedophiles and increased the safety of women and children. There are two things I know for sure as a person who studies porn. First, Kristof’s article resulted in a series of difficulties for sex workers and “amateur performers.” Secondly, even when it is tamped down, desire will find a way to rearticulate itself in new forms and contexts.

Formalization is not without its caveats. In a Dazed article from December 2020, sex workers recount how payment blocks and the removal of their videos from Pornhub—even when they were properly verified—cost them hundreds and thousands of dollars of revenue.[7] In addition, while increased verification measures is a good method for preventing harmful content and putting a stop to piracy, they also limit the kinds and types of pornography that are only available through the protection of anonymity. In an article on Mashable, fellow researcher Brandon Arroyo argues, “Pornhub’s promise of anonymity fostered not just rampant piracy, but also vibrant communities of real amateurs, as well as semi-professional content creators serving highly niche and often marginalized sexual groups.”[8] In short, when child porn is the focus of analyses of a website like Pornhub, it becomes impossible to generate a nuanced understanding of online pornography that consider those who work in the industry.

I realize that by writing this, I risk appearing to diminish the harm of child sexual assault, which is far from my intent. I worry, in fact, that the journalists placing vulnerable children at the center of their stories are misdirecting care from actual targets of sexual harm. Pornhub and MindGeek have lots of problem and I support holding capitalistic mega corporations accountable. But ridding the Internet of Pornhub will not address the issue of child sexual assault. In the conclusion to his column Kristof writes, “The world has often been oblivious to child sexual abuse, from the Catholic Church to the Boy Scouts. . .we should also stand up to corporations that systematically exploit children.”[9] But we are not “oblivious.” It is simply too daunting to admit that sexual abuse is embedded “within a social fabric rather than pitted against it.”[10] In other words, the child pornography on Pornhub and other social media platforms is symptomatic of something much more difficult to address.

Image Credits:

- The enduring moral panic of pornography and personal computing

- A cover that’s meant to represent—and elicit—shock.

- A too on the nose update to an old cautionary tale

- The luring stranger, a familiar trope [author’s screenshot]

- Nicholas Kristof’s article alleges PornHub enables sexual assault on children

- Nicholas Kristof, “The Children of Pornhub: Why does Canada allow this company to profit off videos of exploitation and assault?” New York Times, December 4, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/04/opinion/sunday/pornhub-rape-trafficking.html. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 97. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Gillian Harkins, Virtual Pedophilia: Sex Offender Profiling and U.S. Security Culture (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2020), 4. [↩]

- Nicholas Kristof, “The Children of Pornhub.” [↩]

- Britt Dawson, “How Pornhub’s video purge is hurting sex workers,” Dazed, December

26, 2020, https://www.dazeddigital.com/science-tech/article/51520/1/how-pornhub-video-purge-is-hurting-sex-workers. [↩] - Mark Hay, “Pornhub deleted millions of videos. And then what happened?” Mashable, September 3, 2021, https://mashable.com/article/pornhub-verification-changes. [↩]

- Nicholas Kristof, “The Children of Pornhub.” [↩]

- Gillian Harkins, “Virtual Pedophilia,” 15. [↩]