Speculative Affect: Streaming Television’s Solution to Late-Stage Capitalism

Peter Arne Johnson / University of Texas At Austin

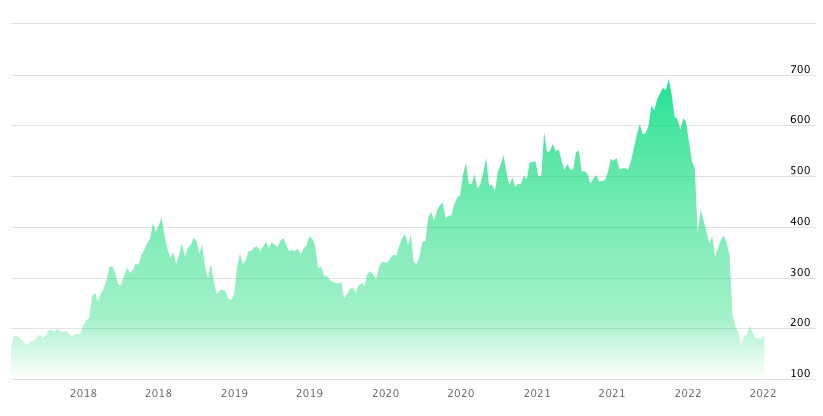

In April 2022, Netflix announced that its aggregate subscriber growth had stalled, and investors (seemingly for the first time) realized that the company never made any real profits, which ultimately eviscerated $225 billion of market value in a few short months. Still, in the face of consistently poor financial metrics, how had Netflix and its peers been able to inflate their financial value so successfully for over a decade? To address this apparent contradiction, this article offers a theory of “speculative affect,” which represents the process by which executives at “pure play” streaming services promote the affective charge of their current subscribers and then speculate on how that charge can be monetized in a future product expansion. In the contemporary political economy of media, the extra-linguistic nature of affect offers a particularly valuable framework. As Brian Massumi (2015, 1) points out, “markets react more like mood rings than self-steering wheels”; therefore, affect’s ambiguity is a welcome concept for executives looking to manufacture value artificially. To ground this theory, I examine Netflix and Paramount’s earnings calls, which offer industry “deep texts” (Caldwell 2008) that reflect the commodification of affect in today’s post-Fordist financialized economy.

The reliance on affect in financial discourses comes amid an idiosyncratic moment in both late-stage capitalism and media industries. In terms of the former, capitalism has become increasingly “financialized,” as the finance sector has grown in relative size over the past four decades (Epstein 2005). Notably, financialization is not simply an external force constraining non-financial activity; it is also an internal process that “re-gears” aspects of everyday life—including our cultural products. Critically, the expansion of financialization has exposed the “central contradiction of capitalism”: the size of accumulated capital requires growth at rates of return higher than what the productive economic base can match (Piketty 2013). In part, this has pushed firms to turn to complex financial strategies to manufacture the return demanded by capital. One discursive tool that executives lean on to create financialized value is speculation, which is useful for television executives in particular because media commodities are largely intangible, symbolic, and affective (Hesmondhalgh 2013) and thereby are more amenable to the “investor lore” (Crawford 2020) that is central to creating a positive narrative on Wall Street.

In addition to macroeconomic shifts, recent changes have led to television-specific crises. First, the audience measurement system Nielsen has briefly fallen out of favor. Concurrently, direct-to-consumer digital platforms, many of which are not supported by advertising or ratings, have proliferated (Lotz 2022). In this political economy, the success of any one title is not as important as growing and maintaining subscriber numbers. These new business models have led to a fundamental reconstitution of the markets for “commodity audiences” (Meehan 1990): although advertisers were the primary “buyers” of audiences in the classic network television era, financial markets have started to replace advertisers as the primary buyers of audiences. Second, tech-media startups have recently faced another industry-specific crisis: “pure play” firms (i.e., undiversified firms with one primary revenue stream) have saturated their “total addressable market” and have no immediate way to increase profits. In the face of such crises, media firms have tried to inflate their valuation not through improved performance but through the “affective economies” (Ahmed 2004) of current subscribers and through speculation. Typically, this strategy unfolds in two stages: 1) emphasize the total affective and emotional economy generated by the platform’s current titles and 2) speculate on how surplus affect can be monetized in the future.

Netflix’s investor lore represents a successful use of this discursive strategy. Indeed, the streamer frequently narrativizes the extreme “passion,” “emotional engagement,” or “delight” of customers when interfacing with security analysts. Notably, this discourse is more than simply executives evoking fandom (though fandom is certainly a component); it is also about speculating and inflating each consumer’s potential future value based on their current connection to a cultural commodity. In a sense, imagined affect serves as a “battery storage” of value that can be “charged up” and exploited in the future—by, for example, increasing prices or diversifying into related sectors or business models (e.g., advertising, theme parks, video games, etc.).

A topic frequently speculated about in Netflix’s earnings calls is gaming. Netflix hired its first executive from the gaming industry in July 2021 and subsequently began a series of acquisitions in the gaming space. Although concrete plans regarding games remain vague, Netflix executives used them as a tool to speculate on future growth throughout 2021.

Deploying the first part of the “speculative affect” strategy, Netflix COO Greg Peters emphasized subscribers’ affective connections to titles in a Q3 2021 call, “it’s just tremendously exciting to see something like Squid Game blow up in the cultural zeitgeist … the passion for the title shows up in all these different places and we definitely want to be part of some of that passion.” Peters would go on to admit that other firms could appropriate this affect: “there’s no monopoly on that passion, so you’ll see it in other places. People are sending around TikTok videos or they’re doing mini-games and Roblox.” In other words, affective connections to Netflix’s titles have spilled over to competitors who exploit Netflix’s fandoms. In response, deploying the second stage of “speculative affect,” Netflix suggested that it could capitalize on this spillover by moving into related products: “we can attach to the passion and fandom that our members have on the video side with game experiences and allow them to go deeper and explore these spaces.” Co-CEO Reed Hastings also hinted at possible Squid Game (Netflix, 2021–Present) extensions in consumer products and other “offline experiences.” Amid these rhetorical acrobatics, affect becomes a financialized storage container of value, wherein more affect indicates more unmonetized passion and thereby more possibilities for future extraction.

An equally illuminating example of the importance of speculative affect is a media corporation that failed to deploy it. In early 2022, the newly renamed Paramount Global announced at an investor meeting that it was fully committing to streaming. Its executives seemingly believed that its library of intellectual property and exclusive “high-quality” streaming programming were sufficient to placate Wall Street. For example, a Paramount executive indicated in that 2022 meeting, “We are creating groundbreaking new IP, even as we lean into the franchises that fans love … The result is entertainment that’s addictive. It’s what entices subscribers and keeps them coming back for more.”

Altogether, the event included 20 mentions of “fandom,” 5 of “IP,” and several additional references to Paramount’s franchises and characters. Although certainly keying in on the importance of audience affect, Paramount’s backward-looking “investor lore” and its simplistic emphasis on new “quality” franchises failed to capture the speculative “emotional architectures” (Wahl-Jorgensen 2019) and forward-looking diversification that financial markets demand. Ultimately, Paramount’s grand gesture toward streaming fell flat: its market capitalization dropped immediately following the presentation.

Although this strategy may be temporary for Netflix, as it moves into advertising and the industry potentially returns to third-party measurement systems, affective economies remain critical sites of commodification in contemporary capitalism. The constant compounding growth that Netflix experienced in the 2010s certainly cannot last forever, but the system that supports this extractionary appropriation of affect—often at the expense of the most marginalized (Clough 2010)—nonetheless perseveres, constantly reinventing itself. Indeed, the engine of capitalism ensures that “all that is solid melts into air” (Marx and Engels [1848], 5). In the case of financialized cultural industries, which already rely on intangible assets, flexible accumulation, and vapid investor lore, perhaps all that was never solid was already air.

Image Credits:

- Netflix Co-CEO Reed Hastings and VP of Investor Relations Spencer Wang dressed in Squid Game costumes for a 2021 Investor Call (author’s screen grabs).

- Netflix’s Stock Price: 2017–2022 (author’s screen grab).

- Visualization of “Speculative Affective Surplus” of SVOD services (created by author).

- Netflix executives deploy “speculative affect” in a Q3 2021 “Video Interview” (20:00-21:30).

- Paramount Global CEO Robert Bakish celebrates Paramount’s top-rated television programs at a 2022 investor event (author’s screen grab).

- Bakish and Paramount Chairman Sheri Redstone in the action-packed introductory video for Paramount’s 2022 investor event, which featured the two executives speeding to the event in a shape-shifting Transformers vehicle (author’s screen grab).

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22 (2): 117–139. muse.jhu.edu/article/55780.

Caldwell, John. 2008. Production Culture: Industrial Reflexivity and Critical Practice in Film and Television. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Clough, Patricia T. 2010. “The Affective Turn: Political Economy, Biomedia, and Bodies.” In The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, 206–225. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Crawford, Colin Jon Mark. 2020. Netflix’s Speculative Fictions: Financializing Platform Television. Landham, MD: Lexington Books.

Epstein, Gerald A. 2005. “Introduction: Financialization and the World Economy.” In Financialization and the World Economy, edited by Gerald A. Epstein, 3–16. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hesmondhalgh, David. 2013. The Cultural Industries. 3rd ed. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

Lotz, Amanda D. 2022. Netflix and Streaming Video: The Business of Subscriber-Funded Video on Demand. New York, NY: Polity Press.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. [1848] 2006. The Communist Manifesto. Perth, Western Australia: Joshua James Press.

Massumi, Brian. 2015. The Power at the End of the Economy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Meehan, Eileen. 1990. “Why We Don’t Count: The Commodity Audience.” In Logics of Television, edited by Patricia Mellencamp, 117–137. Bloomington, IL: Indiana University Press.

Piketty, Thomas. 2013. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wahl-Jorgensen, Karin. 2019. Emotions, Media and Politics. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.