Even Mario lost his job: Insecurity and unionization in video games

Kate Fortmueller / University of Georgia

In 2017, Mario’s Japanese-language profile disclosed a shocking revelation—“Mario is officially no longer a plumber”—reflecting what Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto had said several years before when he stated that “the scenario dictates his role.” Whether Mario’s professional identity was imprinted in pop culture memory from his work in the pipes or the signage in the poorly received film adaptation Super Mario Bros. (Morton and Jankel, 1993), it seems fitting that his career under late capitalism seems to be as unstable as those of the film workers and video game workers who have contributed to his reinvention. All jokes about Mario’s precarity aside, this character’s iconic status has allowed it to move across games, animated television series, and film. While the properties are not equally successful, Mario exemplifies one of the many ways that the film, television, and video game industries intertwine intellectual property.

Contemporary film history is riddled with underwhelming studio attempts to adapt popular video games. While some recent adaptations like Sonic the Hedgehog (Fowler, 2020) have been financially successful, video game adaptations often fail to excite critics. Often this failure is grounded in an adaptation’s ability to translate particular medium specific properties. Speaking about a 2022 attempt to adapt a popular game, critic Roxana Hadadi writes “As a TV show…Halo lacks the immersive capability that has made this franchise so phenomenally successful.” On-screen synergy between games and films or television might be underwhelming on a narrative level, but the labor synergies are more prevalent and tell us more about the nature of the contemporary media industries.

Although there are some noteworthy differences between the film and video game industries, there are distinct similarities between the working conditions. Workers who pursue work in both tech and entertainment industries often work long hours and are driven by passion that can be easily exploited. However, the distinctive industrial histories have led to distinctive labor cultures. In Social Media Entertainment, Stuart Cunningham and David Craig consider the rise of social media entertainment on platforms such as YouTube and Facebook, making note of the differences between Northern (NorCal) and Southern California (SoCal) work cultures. In NorCal’s highly flexible work environment and SoCal’s heavily unionized environments they find an “interdependent clash of industrial cultures.” My last column highlighted one of these clashes between NorCal and SoCal by focusing on the ongoing labor struggles resulting from the increased demand for film and television alongside changes to the streaming landscape. This column focuses on a different clash between Hollywood and tech, the one that resulted in SAG-AFTRA’s 300-day voice actor strike in 2016-2017 and its influence on recent unionization victories in video game studios in 2020 and 2021.

The SAG-AFTRA voice actor contract renewal conversations began in 2015 with eleven major video game studios.[1] At stake for voice actors were three key issues: residuals based on the number of game units sold, transparency in performance expectations and hiring, and the risks associated with vocal strain. As indicated by the names of the studios, SAG-AFTRA was not seeking residuals for all games, just the big budget and highly profitable AAA games, in which games are sold as units and follow a more conventional formula that resembles the unit-based model of VHS or DVD contracts (a profit model that is familiar to the unions and Hollywood studios). Negotiations stalled for months, and, in October 2016, voice actors went on strike.[2]

Hollywood workers often speak up in solidarity with other unions during strikes, but the absence of video game unions combined with the divergent cultural expectations and norms of the video game workplace created conflict across worker sectors. Video game studios are notorious for their spurts of grueling hours, called “crunch,” in which engineers and coders might work 20-hour-days or 100-hour-weeks in order to meet a launch date, only to be laid off after these intense periods of work. In 2004, under the name “ea_spouse,” Erin Hoffman detailed the consequences of working conditions in the video game industry on LiveJournal. The stories of long hours and worker abuse are prevalent; yet, despite ample scholarly and journalistic scrutiny of labor abuses in the industry, the workplace culture has not changed. Instead, workers have found themselves in even more precarious positions for potential layoffs against the backdrop of video game megamergers. Media workers in film and television also work long hours, but if it is a union production they are compensated with overtime and, in particularly dangerous situations, they have recourse to their union representatives (even though complaints aren’t always resolved). Further, game designers and coders are paid salaries, while actors, who typically work for shorter periods of time, receive residual payments compensating for the ways that their individual performances contribute to the longevity of the property. This fundamental difference created conflict when game developers resisted residuals, believing that these payments allowed voice actors to get paid twice for the same work. As striking actors on the now-retired Game Performance Matters website explained, “developers SHOULD get bonuses. … The reason we’re able to go after secondary payments for actors is because we have an established union. … In order to fight for fair treatment, we feel developers need to organize as well.”[3] Video games fulfill many of the same cultural and entertainment audience functions as film and television and create a working culture that shares many key similarities to film and television; however, the structural differences particularly relating to workplace demands and compensation resulted in conflicts and inspired meaningful reflection during the course of the voice actors’ strike.

SAG-AFTRA and the video game companies finally reached an agreement on September 23, 2017, and in the wake of the strike, unionization talks among video game developers escalated. At the 2018 Game Developers Conference, the President of the International Game Developers Association moderated a roundtable titled “Pros, Cons, and Consequences of Union Organization” that included IATSE union organizer Steve Kaplan. Although Hollywood labor unions may have played a part in these early talks of unionization, video game workers have been organizing under the Communication Workers of America’s (CWA) Campaign to Organize Digital Employees (known as CWA-CODE), the union that helped organize the Alphabet Workers Union and focuses on workers in digital media, rather than IATSE’s Rights & Protections for Game Workers organizing unit. For those working in video games, the unionization process has also been different. Hollywood workers are freelance union members who move between projects with different union signatories. In contrast, video game workers are forming bargaining units within their individual companies. Writers for the mobile game Lovestruck: Choose Your Romance unionized after a 21-day strike in summer 2020, indie studio Vodeo Games became the first unionized game studio in North America in December 2021 (studios in Finland, France, Ireland, Scotland, South Korea, Sweden, and the UK have already organized), and as of March 2022, quality control workers at Raven Software (a division of Activision Blizzard) are currently in the process of gaining recognition for their union.

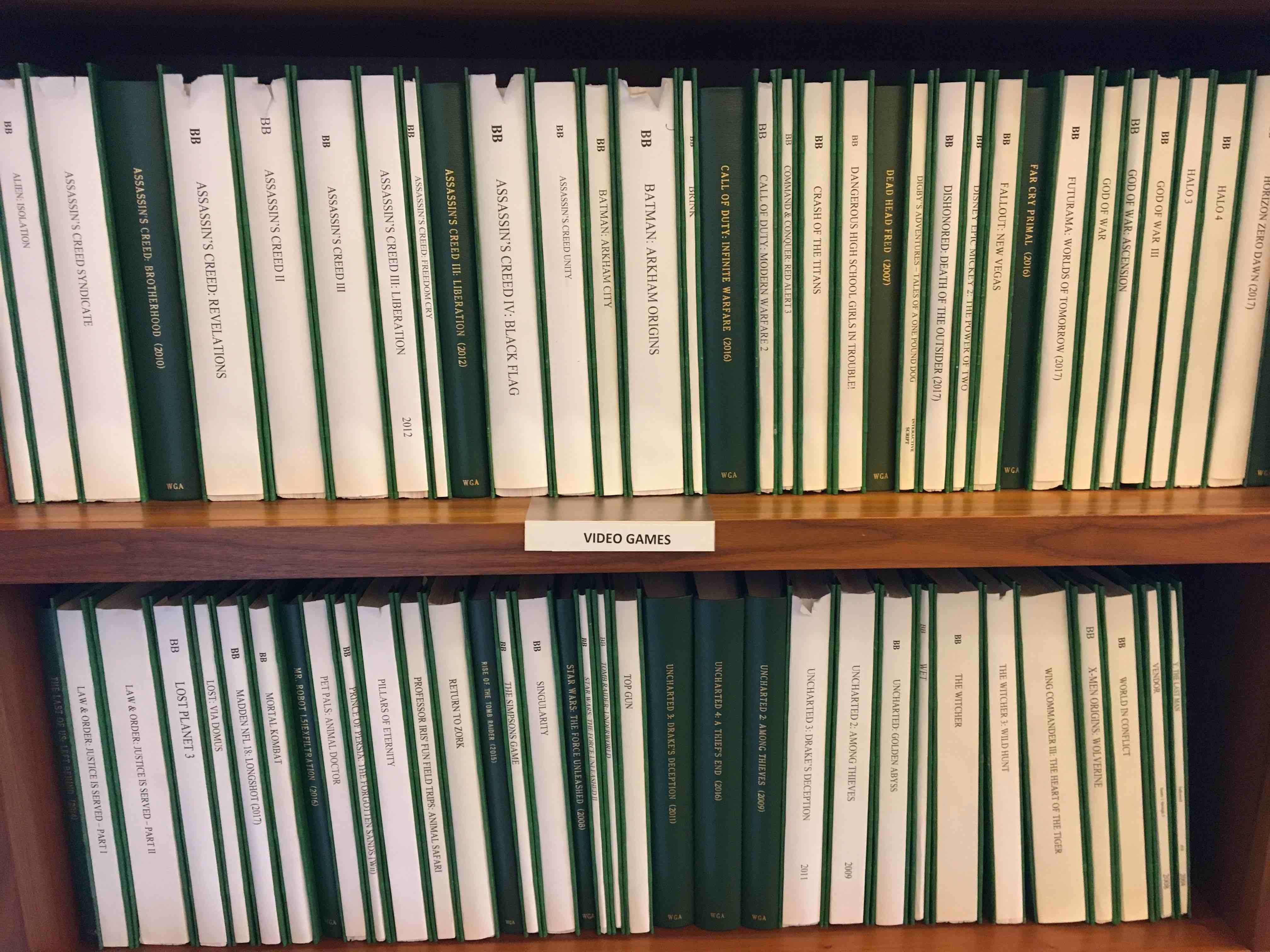

The tech and entertainment industries have different labor histories and worker cultures, but, as recent video game worker actions demonstrate, these stories are becoming increasingly intertwined. The story of the voice actor strike and recent video game unionization efforts demonstrate that while these clashes can be productive, they are also fraught. Another indication of this cultural tension was the Writers Guild of America’s (WGA) 2020 decision to eliminate the video game writing award launched in 2009. The guild cited a low number of games covered by WGA contracts, but game writers lamented that there was no benefit for them to join the guild, as they were not given the same respect as other writers and were only allowed in as non-voting members. Moving forward our theorizing of media industries will need to consider the cultural clashes, flows of labor and organizers across long-separated industry sectors, and broader convergence between Silicon Valley and Hollywood with the fundamental understanding that media work across all sectors—whether writing, coding, or acting—is insecure.

Image Credits:

- The Mario Bros. before they left the plumbing business (author’s screen grab).

- The homepage for Game Performance Matters, which organizers used to provide information and organize virtual picket lines. This site is no longer active (author’s screen grab).

- The logo for the CWA-CODE unit visualizes the convergence of art and technology (author’s screen grab).

- Video game scripts written under WGA contracts at the Writers Guild Foundation Shavelson-Webb Library in Los Angeles, CA. Photo by author in 2018.

- Activision Publishing, Blindlight, Corps of Discovery Films, Disney Character Voices, Electronic Arts Productions, Formosa Interactive, Insomniac Games, Interactive Associates, Take 2 Interactive Software, VoiceWorks Productions, and WB Games. [↩]

- For more details and particulars related to the strike and the labor of voice actors, see: Kate Fortmueller, Below-the-Stars: How the Labor of Working Actors and Extras Shapes Media Production (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2021). For detailed analysis of the voice actor strike coverage, see: Jan Švelch and Jaroslav Švelch, “Recasting Life is Strange: Video Game Voice Acting during the 2016-2017 SAG-AFTRA Strike,” Television & New Media 23.1 (2022): 44-60. [↩]

- “Latest Event Information,” Game Performance Matters, accessed October 11, 2018, http://www.gameperformancematters.com/events. [↩]