Technical Failures as Symptoms of Social Success on Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party

Kara Carmack / The University of Texas at Austin

Technical failures signify an overall system failure—a machine or body that has stopped working as originally intended. In television, video, and film, they may result in unintended glitches, inconsistent sound, acoustic feedback, and blank screens, among other audio-visual malfunctions. But on Glenn O’Brien’s Manhattan public access television show TV Party, as I demonstrate here, the technical failures that signaled and defined the show’s DIY aesthetic are actually signs and symptoms of success—that of a successful party. The healthy and vibrant social body in the studio often led to indifference toward the technical aspects of the show, which in turn resulted in accidental and incidental breakdowns. While the technical failures may have frustrated viewers, those watching could in effect phenomenologically experience the joyous distractions of the in-studio party in the attendant gaps and disruptions. As Jack Halberstam has written on failure, “Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world.”[1] TV Party reveled in and embraced technical failures, inscrutability, and chance in its celebration of collective socializing and its complete disregard for the polished aesthetics and predictability of network television.

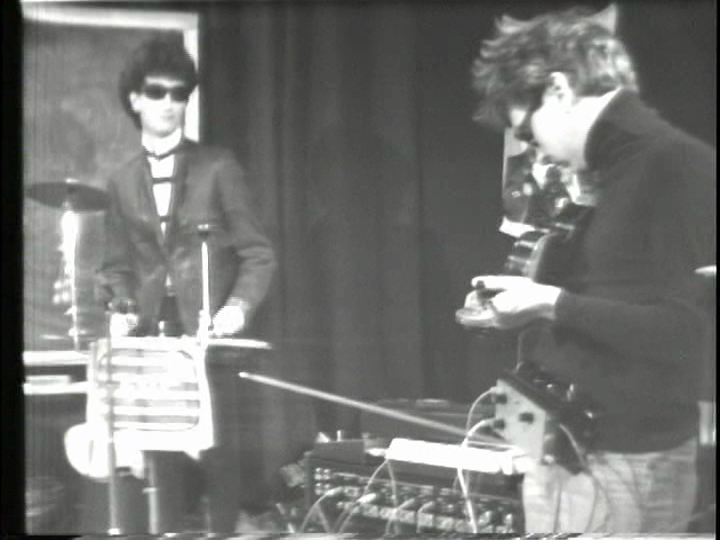

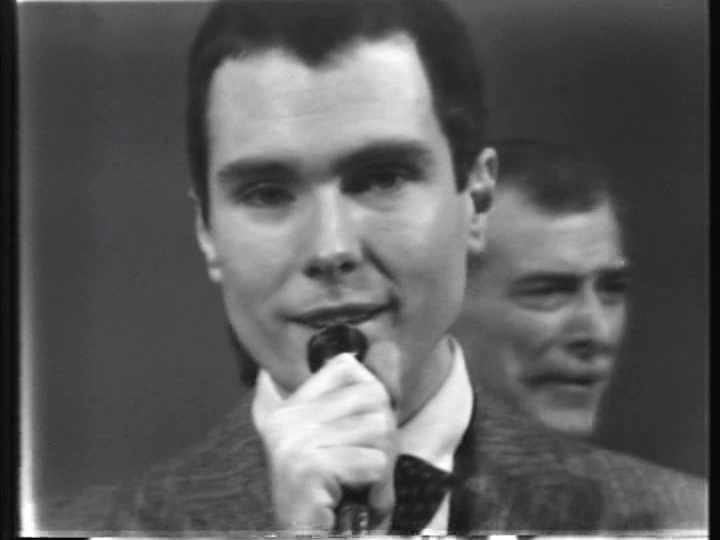

The premise of TV Party, which aired weekly late at night from December 1978 through 1982, is a literal onscreen party, including alcohol, cigarettes, drugs, and live music. Each episode typically begins with introductory music, from either a prerecorded song or a live performance by the house bandmembers Walter “Doc” Steding, with his electric violin and signature synthesizer belt, and Lenny Ferrari on his miniature improvised drum kit made of New Yorker issues, small cymbals, and Quaker Oats cans. The often-incoherent sound matches the quick, disorienting camerawork that rapidly (and randomly) cuts from handwritten title cards to details around the studio, including the wall, the audience, the host, and people’s feet. The dizzying introduction concludes with O’Brien’s standard opening line, “Hi, welcome to TV Party. The TV show that’s a cocktail party, but which could be a political party.” From there, each episode, recorded before a live studio audience seated on folding chairs, embarks on its own rhythm and flow—interviews, jam sessions, jokes, cooking demonstrations, magic tricks, makeovers, dance parties, and call-in segments. O’Brien’s and Chris Stein’s, his co-host and member of Blondie, best efforts at order and timeliness are often undermined, ignored, or forgotten—their only accountability being to the end of the hour when they had to vacate the studio.

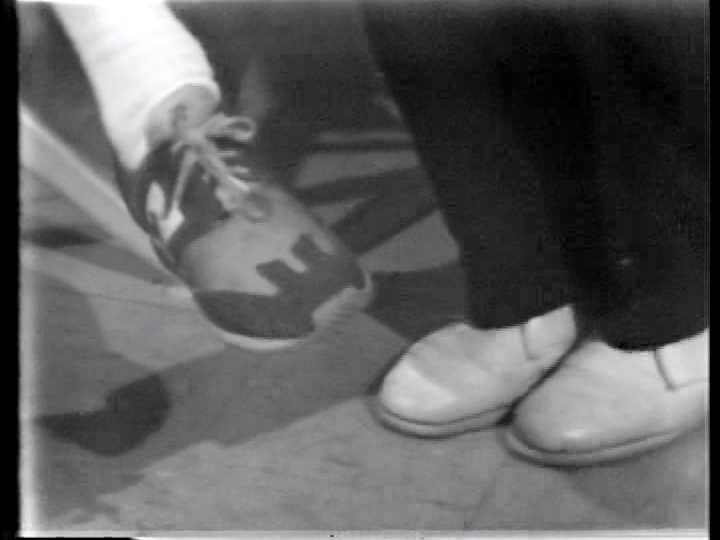

A viewer of TV Party may identify some correspondences to experimental films. Indeed, O’Brien himself acknowledged his indebtedness to those by Andy Warhol: “I was a great fan of his movies and I liked the ‘bad’ camerawork. Somehow the lack of technical slickness heightened the realism and impact of the films. So as long as TV Party looked and sounded as good as Andy’s Nude Restaurant, I was happy.”[2] The look and sound of Nude Restaurant includes shadows cast across the scenes by people casually walking in front of the lights and sounds of footsteps, doors slamming, and casual chatting among cast and crew off-screen. Such apathy toward refinement, perfection, and illusion likewise characterizes TV Party’s production and aesthetic. Audience members regularly walk in front of rolling cameras and sometimes cameramen focus on nothing of particular importance, such as O’Brien’s sneakers or their friend across the room. O’Brien even unabashedly directs the cameras and fixes microphones while onscreen, heightening the informality and extemporized nature of TV Party.

The show, however, deviated from most experimental films in that it was ultimately a series of live, impromptu decisions made by a team of individuals rather than by a single auteur. Despite its experimental aesthetic, as musician Arto Lindsay observes: “It wasn’t like they said, ‘Let’s have the camera do this or that so that we’ll disorient the viewer.’ It was much more like, ‘Eh, it’ll be fine.’”[3] The footage of artist David Walter McDermott performing the 1934 song “If I Had A Million Dollars” on TV Party evinces the show’s cool unconcern for directorial vision and technical prowess.

Competing feeds from multiple cameras produce overlapping ghostly images of McDermott. The sound haphazardly switches from a prerecorded version of the song to McDermott’s live mic. Sometimes both can be heard in sync, at other times, McDermott’s mic is cut off and only the recorded version can be heard. To an unwitting viewer, these may look and sound like technical failures, or mistakes made by untrained technicians, but the most likely explanation is that a few drunk, high, and/or bored operators were merely entertaining themselves in the control room.

The effects of this means of production are recounted later by O’Brien and frequent TV Party guest Debbie Harry on TV Party: The Documentary:

O’Brien: The quality was bad. The picture was out of focus. The sound was faulty. [Director] Amos [Poe] introduced a psychedelic component by pushing a button. It depended on how much he had to drink that night and it could get really out there.

Harry: Amos would sit back there and get really bored. It would be hard to look at.

O’Brien: He made the show really hard to look at it. Making it a Cubist event. … He told the camera people to shoot the shoes or shoot the ear.

Harry: I used to have a really hard time watching the show when he did that.

O’Brien: I think he had something. Nothing like that had ever been on TV before.

The social condition itself directly affected the process of making the final product, as it set aside intentionality and consequence in favor of individual improvisation and experimentation, even if subject to moments of boredom and frustration. TV Party defies categorization and troubles deep readings of its form and content since, as O’Brien recalls, “We were anti-technique, anti-format, anti-establishment, and anti-anti-establishment. … Sometimes we would sit around and say, ‘Well, what should we do now?’ Sometimes we sat there and did nothing. They say ‘dead air’ is the kiss of death in broadcasting, but we liked it. Sometimes we would sit perfectly still like a tape on pause, but it was live.”[4] With disregard for legibility, digestibility, and coherence, TV Party operated on its own impromptu content and aesthetics.

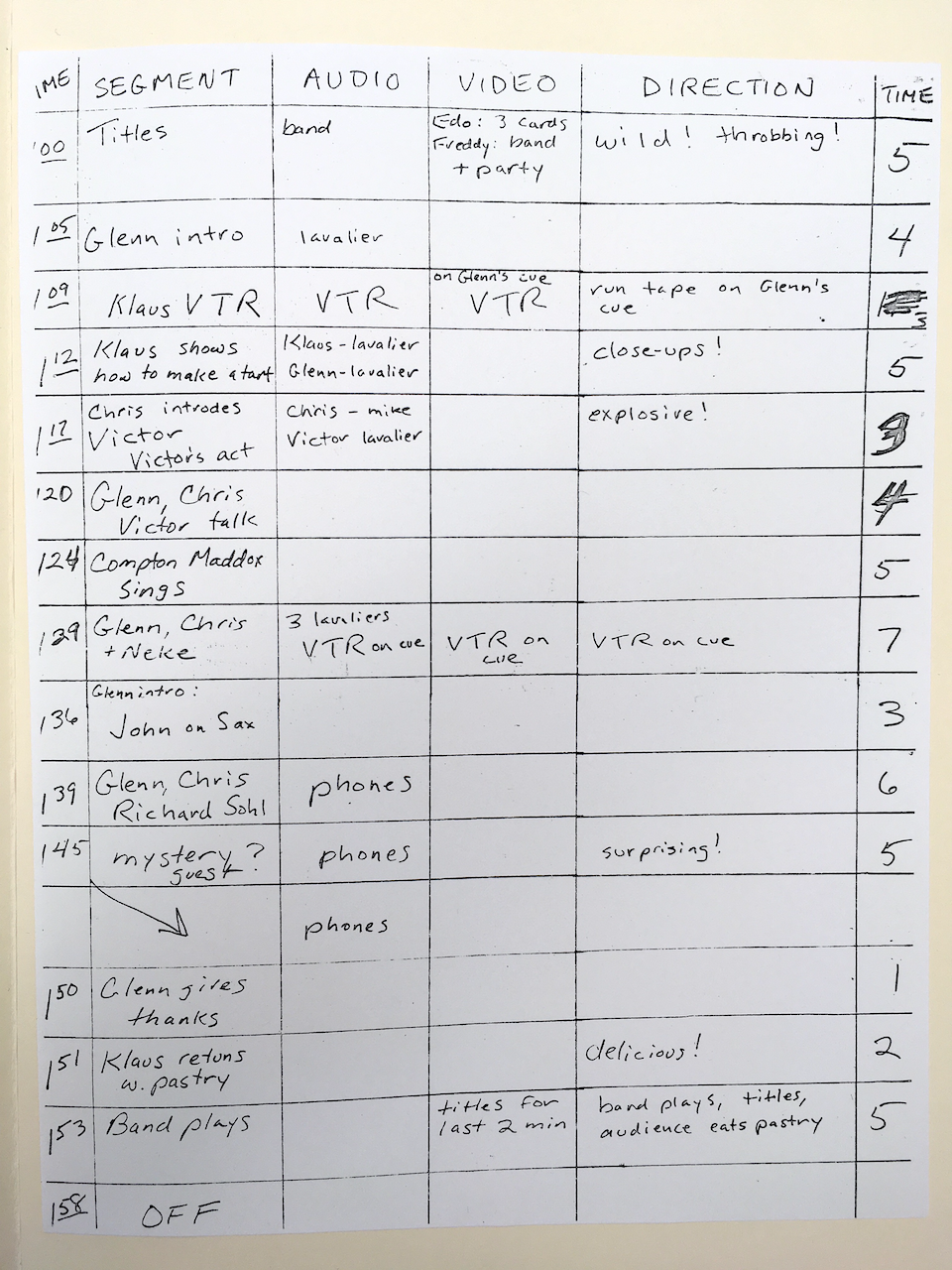

As a live show, anything could happen—segments ran long, were forgotten, ignored, or cut short—so occasionally call sheets were written in an attempt to structure and order the progression of the episodes. In neat columns, they list segments and the accompanying plans for audio, video, direction, and length of time. But for all their attempts at logic and planning, the schedules retain a loose flexibility and a lot of blank space. They are more suggestive than prescriptive, with the notes less than helpful to a camera operator.

According to one sheet, singer Klaus Nomi is to demonstrate how to make a tart at 11:12 PM. Later, when he returns to share the dessert with the audience, the only camera direction on the call sheet is “delicious!” At 11:45 PM on the same episode, a mystery guest is scheduled to join the show. The unidentified guest seems to be a secret to even the person who wrote the call sheet because no other information is given. The direction is simply “surprising!”

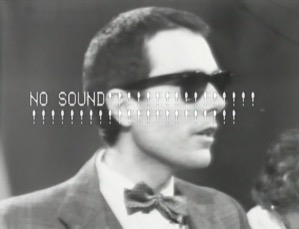

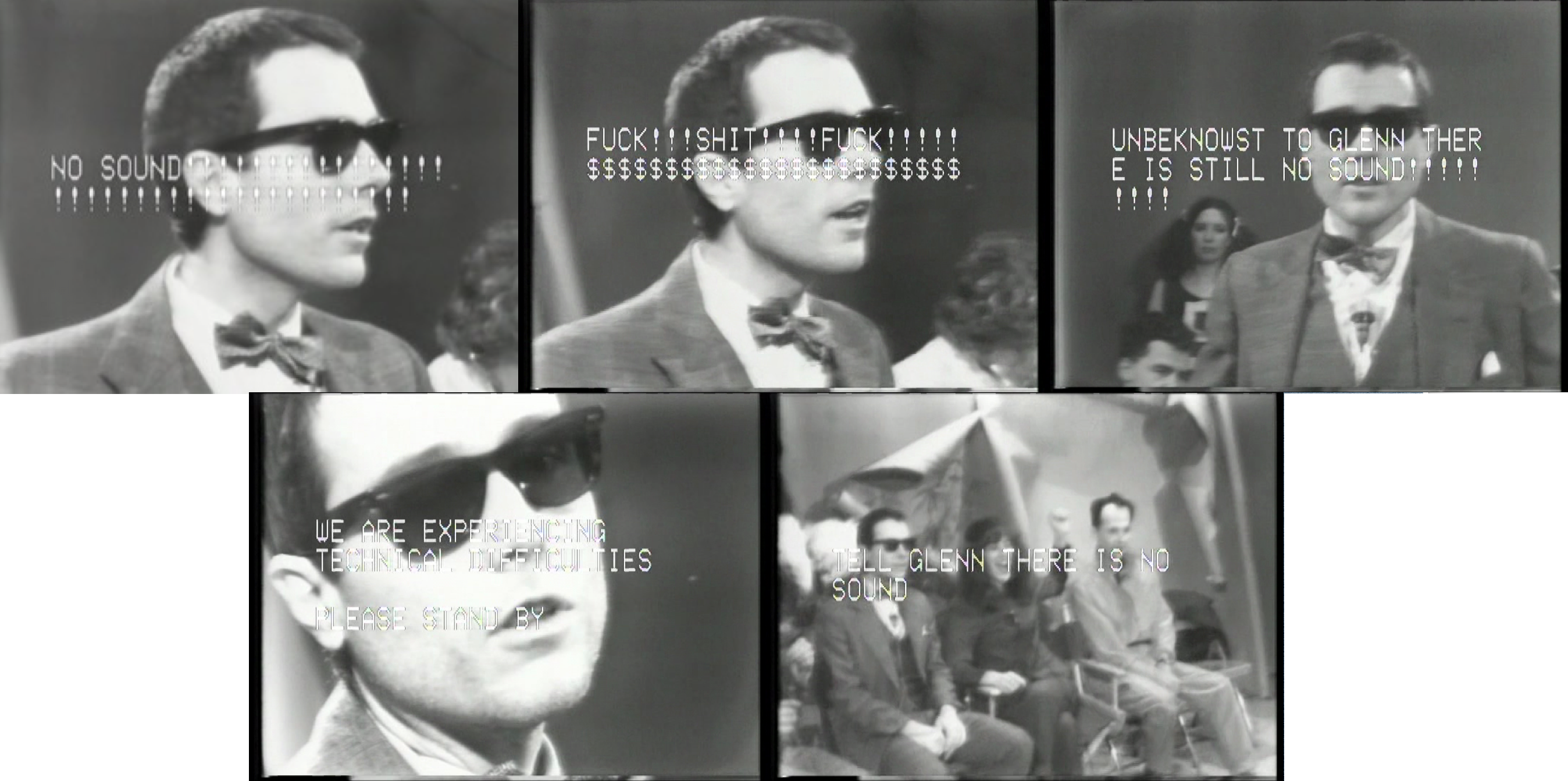

The liveness affected not just the schedule and content, but the technical nature of the show as well. The first ten minutes of “The Sublimely Intolerable Show” exemplifies the hazards and wonders of live television. Shortly after O’Brien opens the show, the technicians lose sound capabilities. Jean-Michel Basquiat and others in the control room take it upon themselves to utilize the character generator to communicate directly to the audience. Viewers see the following flash across their television screen:

NO SOUND!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

FUCK!!!SHIT!!!!FUCK!!!!$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

UNBEKNOWNST TO GLENN THERE IS STILL NO SOUND!!!!!!!!!

WE ARE EXPERIENCING TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES

PLEASE STAND BY

TELL GLENN THERE IS NO SOUND

While O’Brien continues the show unaware of the issues, the text floats across the silent footage. This sudden and unexpected change in the program asks viewers to actively engage with the show because they must unpredictably contend with the written text and silent image. The final line, “Tell Glenn there is no sound,” seems to appeal directly to the viewers, perhaps prompting them to call the studio to alert O’Brien to the technological problems despite those in the control booth being a few feet away. Such failures were embraced by those in the studio. Director Amos Poe recalls that these moments were “quite a lot of fun, allowed me to stay on my toes, and have to improvise when a camera went down, or the communication between myself and the camera operators went down. That meant that sometimes I’d have to run into the studio and tell the camera operator to put down the joint and pay attention. The more chaos in the studio the more fun for the director, is how I felt about it.”[5]

The technical failures on TV Party were the side effects of having a good time—too many drugs and drinks, too loud music, too much talking, too many distractions. As a public access show grounded in antiestablishment rhetoric, the show revels in illegibility and failures, recognizing them, as Halberstam does, “as a way of refusing to acquiesce to dominant logics of power and discipline and as a form of critique. As a practice, failure recognizes that alternatives are embedded already in the dominant and that power is never total or consistent; indeed failure can exploit the unpredictability of ideology and its indeterminate qualities.”[6] TV Party’s lack of seriousness and rigor proposes a counterhegemonic model to the sleekness of network TV and speaks to a productive social ethos so successful that it generated unexpected and fruitful technical failures.

Image Credits:

- Technical problems on “The Sublimely Intolerable Show,” TV Party, January 8, 1979 (author’s screen grab).

- Lenny Ferrari and Walter “Doc” Steding, “The Time and Makeup Show,” TV Party, August 19, 1979 (author’s screen grab).

- Glenn O’Brien introducing the premiere episode, TV Party, December 18, 1978 (author’s screen grab).

- Glenn O’Brien’s shoes, left, next to those of the B-52’s Fred Schneider, “Premiere Episode,” TV Party, December 18, 1978 (author’s screen grab).

- David Walter McDermott performs on TV Party, date unknown (author’s screen grab).

- TV Party call sheet, Amos Poe Papers; MSS 203, box 25, folder 21; Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University Libraries (personal photograph).

- Technical problems on “The Sublimely Intolerable Show,” TV Party, January 8, 1979 (author’s screen grab).

- Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 2-3. [↩]

- Glenn O’Brien, “The TV Party Story,” TV Party: The TV Show That’s a Party!, https://www.tvpartythemovie.com/. [↩]

- Arto Linday, quoted in TV Party: The Documentary, directed by Danny Vinik (New York: Brink Films, 2005). [↩]

- O’Brien, “The TV Party Story.” [↩]

- Amos Poe, correspondence with the author, November 18, 2017. [↩]

- Halberstam, 88. [↩]

What makes a successful person? What qualities do they possess that make them attractive to others? This is not an easy question to answer, but social psychology has provided some deep insight into the topic.